Woody Guthrie didn't just write songs; he documented a collapse. When you look at the i ain't got no home lyrics, you aren't just reading a rhyme scheme about being broke. You're reading a primary source document from the Dust Bowl. It’s raw. Honestly, it’s a bit mean-spirited toward the people in power at the time, which is exactly why it still feels so punchy today. Guthrie was wandering around the country in the 1930s, seeing families literally starving on the side of the road, and he decided to flip a gospel hymn on its head to make a point.

Most people don't realize that this song is a direct parody. There was a popular Baptist hymn called "Can’t Feel at Home," which talked about how this world isn't our home because we're all just passing through on the way to heaven. Woody hated that. He thought it was a "pie in the sky" excuse to keep poor people from complaining about their miserable living conditions. So, he took the melody and wrote the i ain't got no home lyrics as a middle finger to that sentiment. He was basically saying, "I don't have a home here, but it's not because I'm going to heaven—it's because the bankers took it."

The Brutal Reality Behind the Verses

The song opens with a line that sounds like a weary sigh: "I ain't got no home, I'm just a-roamin' 'round." It’s simple. It’s repetitive. Guthrie uses that repetition to simulate the actual physical exhaustion of a migrant worker. Imagine walking from Oklahoma to California with nothing but a guitar and a bad cough.

In the second verse, things get specific. He mentions being in the town and in the city. He talks about the police. This wasn't just flavor text. During the Great Depression, vagrancy laws were used as a weapon. If you didn't have money in your pocket, you were a criminal. Guthrie's lyrics reflect the "bum blockades" where police would literally stop people at state borders to keep the "Okies" out.

"The police make it hard wherever I may go."

That isn't just a grievance; it was a daily reality for thousands of people living in Hoovervilles. Guthrie himself lived this. He wasn't some observer in a high-rise. He was the guy sleeping in the boxcar. He saw the "rich man" taking the profits and the "poor man" losing the corn. It’s a zero-sum game in his eyes. He wasn't interested in nuance because the hunger he saw didn't have nuance.

Why the "Gambling Man" Reference Matters

There's a line about the "gambling man" that often gets overlooked. In the context of the 1930s, gambling wasn't just about cards or dice. Guthrie was talking about the speculation that led to the 1929 crash. To him, the bankers and the big farm owners were gamblers playing with other people's lives.

🔗 Read more: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

He writes: "The gambling man is rich and the working man is poor."

It’s almost too simple, right? But that’s the genius of Guthrie. He takes complex economic failure and boils it down to a playground truth. You work, you lose. They bet, they win. It’s a cycle of dispossession. If you look at the i ain't got no home lyrics through the lens of 2026, it’s wild how much of it still resonates with the current housing crisis. We aren't in a Dust Bowl, but the feeling of being priced out of your own "home" is a universal frequency Guthrie tapped into.

The Religious Subversion You Might Have Missed

As I mentioned earlier, the religious aspect is the secret sauce of this song. Guthrie was famously skeptical of organized religion when it was used to justify suffering. By using a gospel melody for a song about homelessness, he was performing a kind of musical protest.

Think about the original hymn's message: This world is not my home, I'm just passing through.

Now look at Guthrie's version: I ain't got no home, I'm just a-roamin' 'round.

One is a choice; the other is a sentence.

Guthrie’s narrator isn't "passing through" toward a better world; he’s trapped in this one. He mentions his brothers and sisters are stranded, too. This is a call for solidarity, not salvation. He’s telling the listener that if we're all "homeless," we might as well be homeless together. This shift from "I" to "we" is a hallmark of Guthrie’s work, from "This Land Is Your Land" to his more obscure stuff.

💡 You might also like: The A Wrinkle in Time Cast: Why This Massive Star Power Didn't Save the Movie

The Evolution of the Song Through Covers

You can't talk about these lyrics without talking about who else has sung them. Bruce Springsteen did a version for the Folkways: A Vision Shared tribute album in 1988. Springsteen, being Springsteen, turned up the grit. He emphasized the line "I'm a rambling gambling man," which adds a layer of defiance that Guthrie’s flatter, more nasal delivery sometimes hid.

Then you have Bob Dylan. Dylan basically modeled his entire early persona on Guthrie. When Dylan performs Guthrie songs, he treats the lyrics like scripture. But there’s a difference in how they approach the "homelessness" theme. Guthrie's lyrics are grounded in material poverty—no food, no bed, no job. Dylan eventually moved into metaphorical homelessness, but he started with the literal struggle he learned from these verses.

Even Cisco Houston and Pete Seeger kept this song alive in the 50s and 60s. Each time someone covers it, the i ain't got no home lyrics get updated with a new social context. In the 60s, it was about civil rights and the urban poor. Today, it’s played at labor rallies. It’s a "living" lyric sheet.

A Technical Look at the Songwriting

Guthrie wasn't trying to win a Pulitzer for poetry. He was writing for the ear of a person who might only hear the song once.

- Rhyme Scheme: It’s a basic AABB or ABCB structure. It's designed to be remembered.

- Meter: It follows a walking pace. Literally. The tempo is usually around 100-110 BPM, which is the speed of a steady stride.

- Diction: He uses vernacular like "a-roamin'" and "a-blowin'." This wasn't an accident. He wanted to sound like the people he was writing for. If he used high-brow language, the message would have felt like a lecture. Instead, it feels like a conversation over a campfire.

The line "I was farmed out of my home" is particularly striking. He doesn't say he was evicted. He says he was "farmed out." It implies that the land itself—or the system of farming—rejected him. It turns the earth into a character that has turned its back on the worker.

The Missing Verses and Variations

Depending on which recording you find, the lyrics change. Guthrie was notorious for adding verses on the fly. In some versions, he goes harder on the "bosses." In others, he focuses more on the loneliness of the road.

📖 Related: Cuba Gooding Jr OJ: Why the Performance Everyone Hated Was Actually Genius

One rare variation includes a more direct attack on the "six-shooters" of the deputies. It highlights the violence inherent in the migrant experience. If you're looking for the "definitive" version, the 1940 Dust Bowl Ballads recording is the gold standard. That’s where the raw, unpolished anger of the i ain't got no home lyrics is most evident.

How to Apply Guthrie's Perspective Today

If you’re a musician or a writer looking at these lyrics for inspiration, don't just copy the words. Copy the intent. Guthrie’s "expert" move was identifying a specific injustice and giving it a human face. He didn't write about "macroeconomic fluctuations in the agricultural sector." He wrote about a guy who hasn't seen his wife in months and has holes in his shoes.

To truly understand the i ain't got no home lyrics, you have to look at your own surroundings. Who are the "gambling men" today? What are the modern-day "bum blockades"?

Practical Steps for Exploring Guthrie’s Legacy:

- Listen to the "Dust Bowl Ballads" album in full. It provides the narrative context that this single song sits within. You'll see how "I Ain't Got No Home" connects to "Vigilante Man."

- Compare the lyrics to the photography of Dorothea Lange. Her photos of "Migrant Mother" are the visual equivalent of Guthrie’s stanzas. Seeing the faces makes the lyrics hit ten times harder.

- Read "Bound for Glory." Guthrie's autobiography is... let's call it "creatively factual." It’s a semi-fictionalized account of his life, but it captures the vibe of why he wrote these songs better than any history book.

- Analyze the "answer song" format. Try writing your own verse to the melody. Guthrie encouraged people to change his songs. He believed music was a communal tool, not a static piece of art.

Guthrie's work reminds us that "home" isn't just a building. It's a sense of belonging and security that can be stripped away by forces far larger than an individual. That’s why we’re still talking about these lyrics nearly a century later. They aren't just a "folk song." They are a warning.

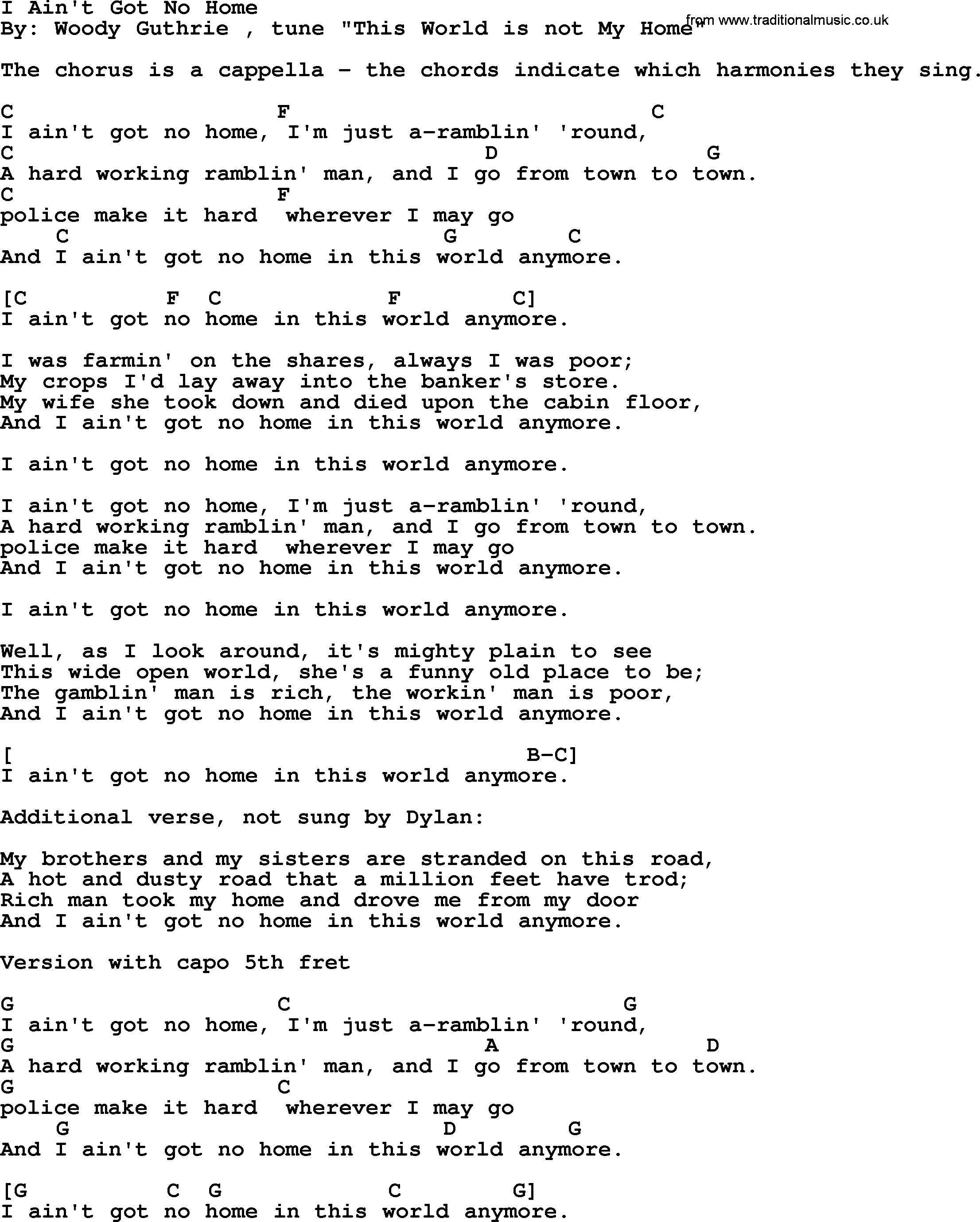

The song doesn't end with a solution. There is no "and then everything got better" verse. It ends with the singer still roamin'. It leaves the listener with the discomfort of the unresolved. That’s the most honest way it could have ended. If you're looking for the sheet music or the specific chord progressions, you'll find they are almost entirely C, F, and G. Simple chords for a complicated life.