You probably wouldn't expect a drunken story about a preacher losing his virginity in an outhouse to be the cornerstone of American democracy. Honestly, it sounds like the setup for a bad joke. But in 1983, Larry Flynt decided to run exactly that in Hustler magazine, and the legal fallout basically changed the First Amendment forever. Hustler Magazine v Falwell wasn't just a spat between a pornographer and a televangelist; it was the moment the Supreme Court had to decide if being offensive was a crime.

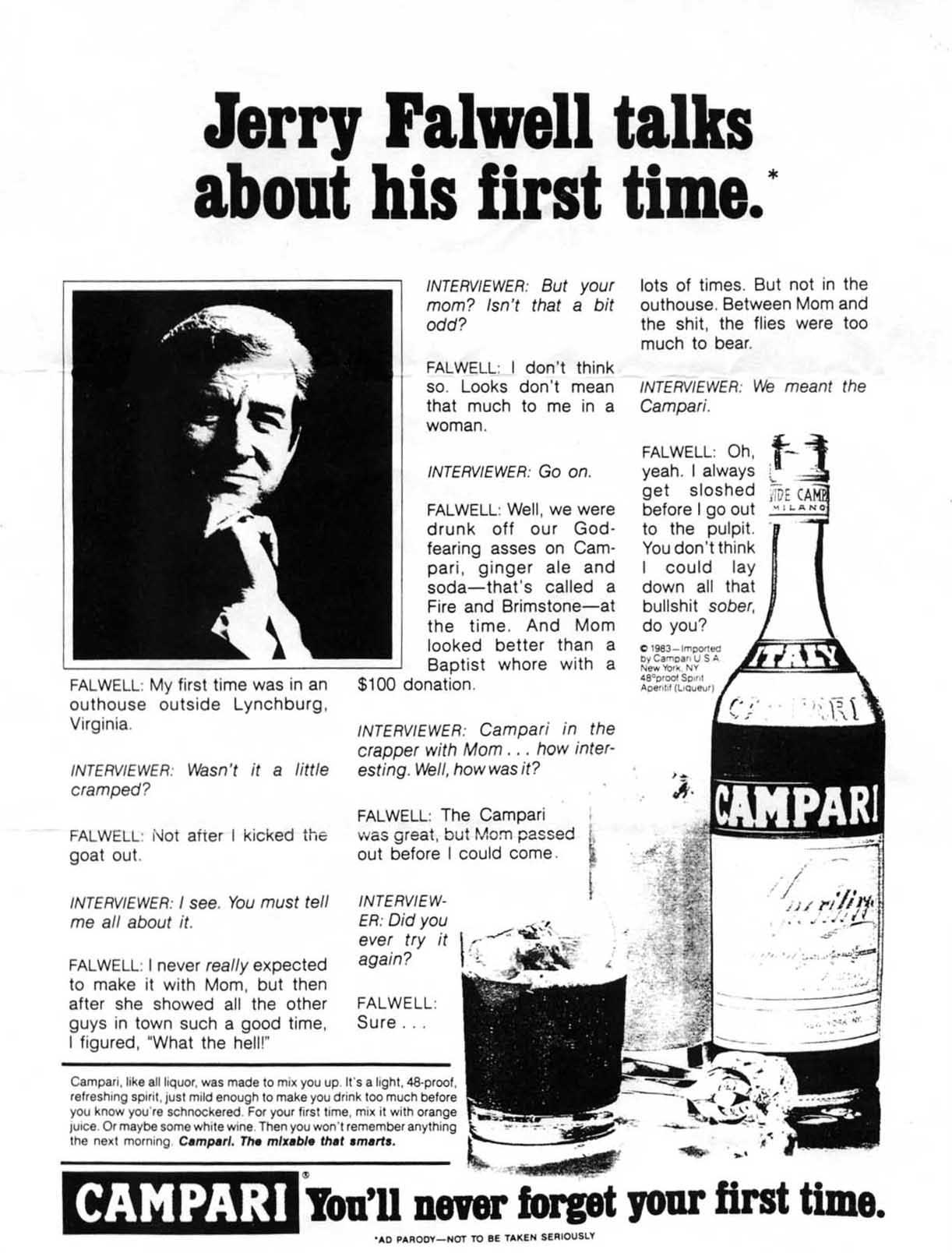

Jerry Falwell was a giant. He founded the Moral Majority. He had millions of followers and massive political sway. Then there was Larry Flynt, the self-proclaimed "scumbag" who delighted in pushing every button possible. When Hustler published a parody ad for Campari Liqueur—mimicking a real campaign where celebrities talked about their "first time"—they featured Falwell. The "first time" in the ad wasn't about booze, though. It was a fake interview where Falwell "admitted" to a drunken encounter with his mother in an outhouse.

Falwell sued for $45 million. He won a chunk of it at first, but not for libel. He won for "intentional infliction of emotional distress." That’s where things got dangerous for every late-night host, cartoonist, and satirist in the country.

The Ad That Started a War

The parody was crude. Even by 1980s standards, it was bottom-of-the-barrel humor. At the bottom of the page, in tiny print, Hustler included a disclaimer: "Ad parody—not to be taken seriously."

Falwell didn’t care about the disclaimer. He claimed the ad was a malicious attack on his character. When the case reached a jury in Virginia, they actually rejected the libel claim. Why? Because the ad was so ridiculous that no reasonable person could possibly believe it was a factual account. You can’t "defame" someone with a story that everyone knows is fake.

💡 You might also like: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

However, the jury did award Falwell $200,000 for the emotional pain the ad caused him. This created a massive legal loophole. If you couldn't sue a satirist for libel because people knew they were joking, you could just sue them for making you feel bad. If that ruling had stayed, Saturday Night Live wouldn't exist. Political cartoonists would have been sued into bankruptcy decades ago. It would have meant that "hurt feelings" were enough to bypass the First Amendment.

Why the Supreme Court Sided With the "Bad Guy"

By the time the case hit the Supreme Court in 1987, the stakes were astronomical. Chief Justice William Rehnquist was a conservative. Most people expected him to side with Falwell, a fellow conservative leader. But Rehnquist surprised everyone.

The Court realized that in a free society, "outrageousness" is subjective. What offends a preacher might not offend a biker. If you allow juries to punish people just because a joke is "outrageous," you essentially give the government the power to decide what ideas are allowed to exist. Rehnquist wrote the unanimous opinion. He argued that even if a speaker's intent is malicious, we have to protect it to ensure "breathing space" for the First Amendment.

Public figures have to be thick-skinned. That’s the trade-off. If you want the power and the platform of a public official or a religious leader, you have to accept that people—even "vile" people like Larry Flynt—get to make fun of you. Hustler Magazine v Falwell established that to win an emotional distress claim, a public figure has to prove "actual malice." They have to prove the publisher knew something was false or acted with reckless disregard for the truth. Since everyone knew the outhouse story was a joke, there was no "falsehood" to prove.

📖 Related: Effingham County Jail Bookings 72 Hours: What Really Happened

The Impact on Modern Media

Think about the memes you see every day. Think about the brutal caricatures on South Park or the way late-night hosts rip into politicians. All of that flows from this 1988 decision.

Before this case, the standard was a bit murky. After it, the line was drawn in concrete: if it’s clearly satire or parody, it’s protected. This protects the "small" creators just as much as the big ones. It ensures that the person with the loudest voice or the biggest bank account can't silence critics just by claiming they are "distressed."

Some Realities People Miss

- It wasn't about liking Flynt. The ACLU and various news organizations filed briefs supporting Hustler, not because they liked the magazine, but because they feared the precedent of Falwell winning.

- The Mother factor. Falwell was particularly incensed because the ad targeted his mother, who had passed away. He felt it was a violation of family sanctity, not just a political attack.

- The "Actual Malice" Standard. This comes from New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, but the Falwell case extended it specifically to claims of emotional distress.

The Unlikely Friendship

Here is a weird bit of history most people forget: Flynt and Falwell actually became friends later in life. After years of legal battling, they ended up touring college campuses together to debate the First Amendment. They swapped Christmas cards. Flynt even wrote an op-ed after Falwell died in 2007, saying he genuinely liked the guy even though they disagreed on everything.

It’s a strange ending to a story that started with an outhouse joke. It shows that the legal system did its job—it separated the personal animosity from the constitutional principle.

👉 See also: Joseph Stalin Political Party: What Most People Get Wrong

Practical Takeaways for Creators and Critics

If you are a writer, a creator, or just someone who posts opinions online, Hustler Magazine v Falwell is your shield. But there are limits.

- Parody must be recognizable. The "not to be taken seriously" disclaimer helped Hustler, but the absurdity of the content helped more. If you write something that looks exactly like a real news report and people believe it’s true, you’re back in libel territory.

- Public figure status matters. This protection is strongest when you are talking about "public figures." If you do this to a private citizen who isn't seeking the spotlight, the courts are much less likely to protect you.

- Intent isn't everything. Even if you hate the person you are satirizing, the law cares more about whether the audience understands it’s a joke than whether you were being "mean."

Next Steps for Understanding Free Speech Law

To truly get how these protections work today, you should look into Anti-SLAPP laws in your state. These are "Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation" statutes. They are designed to quickly throw out lawsuits—like Falwell’s—that are intended to silence critics through expensive legal fees.

You should also research the "Reasonable Person Standard." This is the legal yardstick used to determine if a piece of content is a joke or a statement of fact. Understanding this helps you stay on the right side of the law while still exercising your right to be critical, funny, or even a little bit outrageous.

Freedom of speech isn't just for the polite stuff. It’s specifically for the stuff that makes people uncomfortable. Without the precedent set by a smut peddler and a preacher in the 80s, our digital world would be a much quieter, and much more censored, place.