The sky goes a weird, bruised shade of purple. You’ve seen it if you live anywhere from the Florida Keys up to the Maine coastline. It’s that eerie, breathless calm right before the wind starts screaming. People talk about hurricanes that hit east coast like they're just one singular type of disaster, but honestly, a Category 1 in North Carolina feels nothing like a Category 1 in New Jersey. The geography changes the stakes entirely.

We’ve become obsessed with the "cone of uncertainty." We stare at those colorful maps on the news, waiting for the line to shift five miles left or right. But here’s the thing: the cone is actually kind of misleading. It only predicts where the center of the storm might go. It says nothing about how far the rain will reach or if the storm surge is going to swallow your driveway.

The Geography of the Atlantic Seaboard

The East Coast isn't a straight line. It's a jagged mess of barrier islands, shallow sounds, and deep bays. When hurricanes that hit east coast move north, they aren't just fighting the wind; they’re interacting with the Gulf Stream. That warm current is like high-octane fuel for a spinning storm.

Take Sandy in 2012. Technically, by the time it made landfall in New Jersey, it wasn't even a "hurricane" anymore—it was a post-tropical cyclone. But tell that to the people in Breezy Point whose houses burned down or the folks in Hoboken whose basements became swimming pools. Because the storm hit at high tide during a full moon, the water had nowhere to go but inland. The "category" didn't matter. The timing did.

Why the "Big One" is Always Different

Everyone remembers 1938. The "Long Island Express" moved so fast—about 50 mph—that people didn't even know it was coming until the ocean was in their living rooms.

👉 See also: When Will Pot Be Legal in TN: What Most People Get Wrong

Compare that to Hurricane Ian or Florence. Those storms weren't fast. They were slow, agonizing deluges. Florence basically sat on top of the Carolinas and dumped trillions of gallons of water. It wasn't the wind that broke the state; it was the fact that the rivers literally couldn't drain into the ocean because the storm was pushing the ocean back up the rivers.

We often think about the wind speeds first.

110 mph.

130 mph.

155 mph.

But water is the real killer. Roughly 90% of deaths in these storms come from water, specifically the storm surge and inland flooding. If you’re looking at a map of hurricanes that hit east coast and you’re only checking the wind category, you’re missing the biggest threat.

The Science of the "Wobble"

National Hurricane Center (NHC) forecasters, like the legendary Ken Graham or the current team in Miami, will tell you that "wobbles" are the bane of their existence. A hurricane isn't a point on a map. It's a massive, chaotic engine.

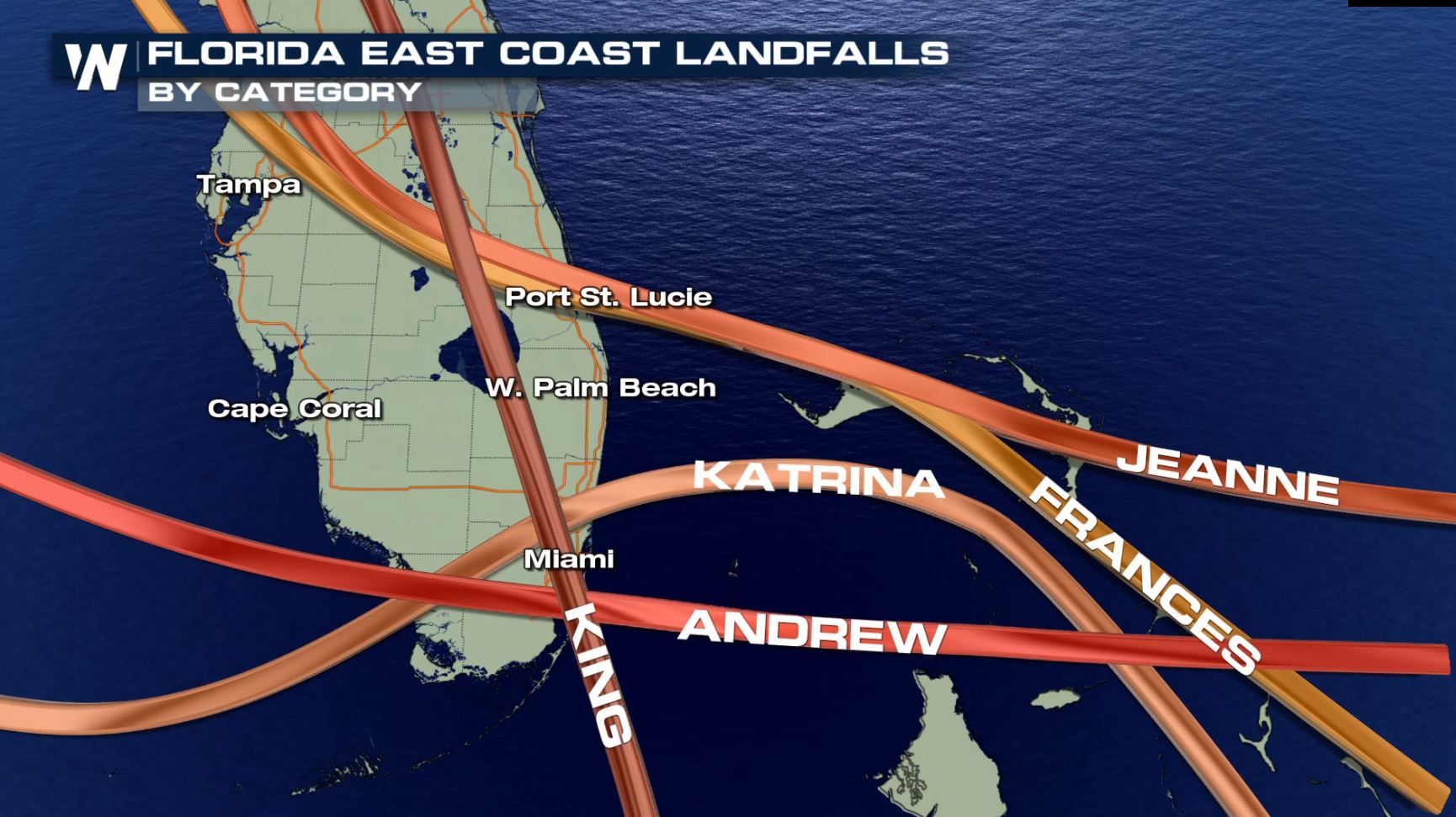

If a storm wobbles 20 miles to the east, it might stay offshore and just give the coast a rainy day. If it wobbles 20 miles west? You’re looking at billions in damages. This happened with Hurricane Charley in 2004. Everyone thought it was heading for Tampa. At the last second, it tightened up, turned, and shredded Punta Gorda. People were prepared for a brush, not a direct hit from a Category 4 buzzsaw.

Predicting Hurricanes That Hit East Coast

Modern meteorology is incredible, but it has limits. We have European models (ECMWF) and American models (GFS). Sometimes they agree. Often, they don’t. The "Euro" is famous for picking up Sandy’s weird left turn days before the American models did, but the GFS has had its own wins lately, especially with storms forming in the Gulf and crossing over Florida.

Data comes from everywhere now:

- Hurricane Hunters: These pilots actually fly Lockheed WP-3D Orions directly into the eyewall. It’s bumpy. It’s dangerous. But dropping "sondes" (sensor packages) into the storm is the only way to get real-time pressure and wind data.

- Deep-Sea Buoys: These measure the water temperature way below the surface. If the warm water is deep, the storm can keep feeding. If it's just a thin layer of warm water, the storm might "churn up" cold water and weaken itself.

- Satellites: GOES-16 provides high-res images every 30 seconds. We can see the eye clearing out in near real-time.

The Infrastructure Gap

The scary reality of hurricanes that hit east coast is that our buildings aren't always ready for the "new" normal. In the South, building codes are generally stricter because they expect the wind. In the North, many homes are older and built for snow loads, not 100 mph sustained winds or massive storm surges.

When a storm like Ida (2021) hits, it doesn't just impact the coast. It travels inland. Ida caused more deaths in New York and New Jersey from basement flooding than it did in some parts of the South where it first hit. Our drainage systems in cities like Philly and NYC were built for 20th-century rain, not 21st-century tropical deluges.

Misconceptions About Heat and Strength

It's a common trope: "It’s a hot summer, so the hurricanes will be huge."

While warm water is the fuel, wind shear is the fire extinguisher. You can have the warmest Atlantic in history, but if there’s a lot of "shear"—winds at different altitudes blowing in different directions—it rips the tops off the storms before they can organize. This is why some years are surprisingly quiet despite record-breaking heat.

Also, don't trust the "it's just a Category 1" talk. A large, slow Category 1 can be significantly more destructive than a tiny, fast-moving Category 3. Size matters. A massive storm pushes a much larger "mound" of water toward the shore. That's the surge. It’s like a bulldozer made of ocean.

👉 See also: The Black Regiment Civil War Records Most People Miss

Living with the Risk

If you live within 50 miles of the Atlantic, you basically have a seasonal contract with anxiety from June to November. But panic is useless. Preparation is the only thing that actually lowers the stakes.

The biggest mistake people make?

Staying because "the last one wasn't that bad."

Every storm has a unique fingerprint. The angle of approach matters. A storm hitting the coast at a 90-degree angle is going to push way more water into the bays than one that brushes by at an angle.

Actionable Steps for the Next Season

Understanding the risks of hurricanes that hit east coast means moving beyond just watching the news the day before landfall.

Audit Your Elevation

Don't just look at a flood map. Find out your actual "Base Flood Elevation" (BFE). If your house is at 10 feet and the predicted surge is 11 feet, you’re in trouble. Most people don't know their number until the water is at the door.

The 5-Day Rule

When a storm enters the 5-day forecast window, that's when you do the "heavy" prep. Gas up the cars. Check the generator. If you wait until the 2-day warning, the shelves at Home Depot will be empty and the gas stations will be out of premium.

Digital Backup

Take a video of every room in your house. Open the closets. Record the serial numbers on your TV and appliances. If you have to file an insurance claim after a storm, having a "before" video is worth thousands of dollars. Upload it to the cloud immediately.

Understand Your Insurance

Standard homeowners insurance almost never covers rising water. You need a separate flood policy through the NFIP or a private carrier. There is usually a 30-day waiting period for these policies to kick in, so you can't buy it when the storm is already in the Bahamas.

Evacuation Logistics

Know exactly where you are going. If you have pets, find a pet-friendly hotel 200 miles inland now. Don't rely on public shelters unless you absolutely have to. Have a "go-bag" with your birth certificates, insurance policies, and enough meds for two weeks.

The coast is a beautiful place to live, but it comes with a price. Respecting the power of these systems means acknowledging that we are guests in a landscape that the ocean occasionally wants to reclaim. Stay informed, keep your batteries charged, and never underestimate a storm just because it’s "only" a Category 1.