You’re standing in your kitchen, the sky is a weird shade of bruised purple, and the local news anchor is pointing at a swirling mass of pixels on the radar. They keep saying "Category 3." You check a hurricane wind speed chart on your phone, see the numbers 111 to 129 mph, and think, Okay, I can handle that. But here’s the thing. That chart—the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale—is kinda like judging a book by its font size. It tells you something, sure, but it misses the plot.

I’ve spent years looking at how we talk about weather, and honestly, the way we use the hurricane wind speed chart is a bit broken. We treat it like a scoreboard where the highest number wins. In reality, a "weak" Category 1 can sometimes be way more lethal than a "major" Category 3. It depends on where you are, how fast the storm is moving, and how much water it’s dragging along for the ride.

What the Saffir-Simpson Scale Actually Measures

Let's get the technical stuff out of the way first. Herbert Saffir and Robert Simpson developed this thing back in the early 1970s. Saffir was an engineer; Simpson was a meteorologist. They wanted a way to explain how wind would likely wreck buildings.

The hurricane wind speed chart is strictly about sustained wind. We’re talking about a one-minute average measured at 33 feet (10 meters) above the ground. It doesn't account for gusts. It doesn't account for rain. It definitely doesn't account for storm surge, which is the big killer.

The Breakdown

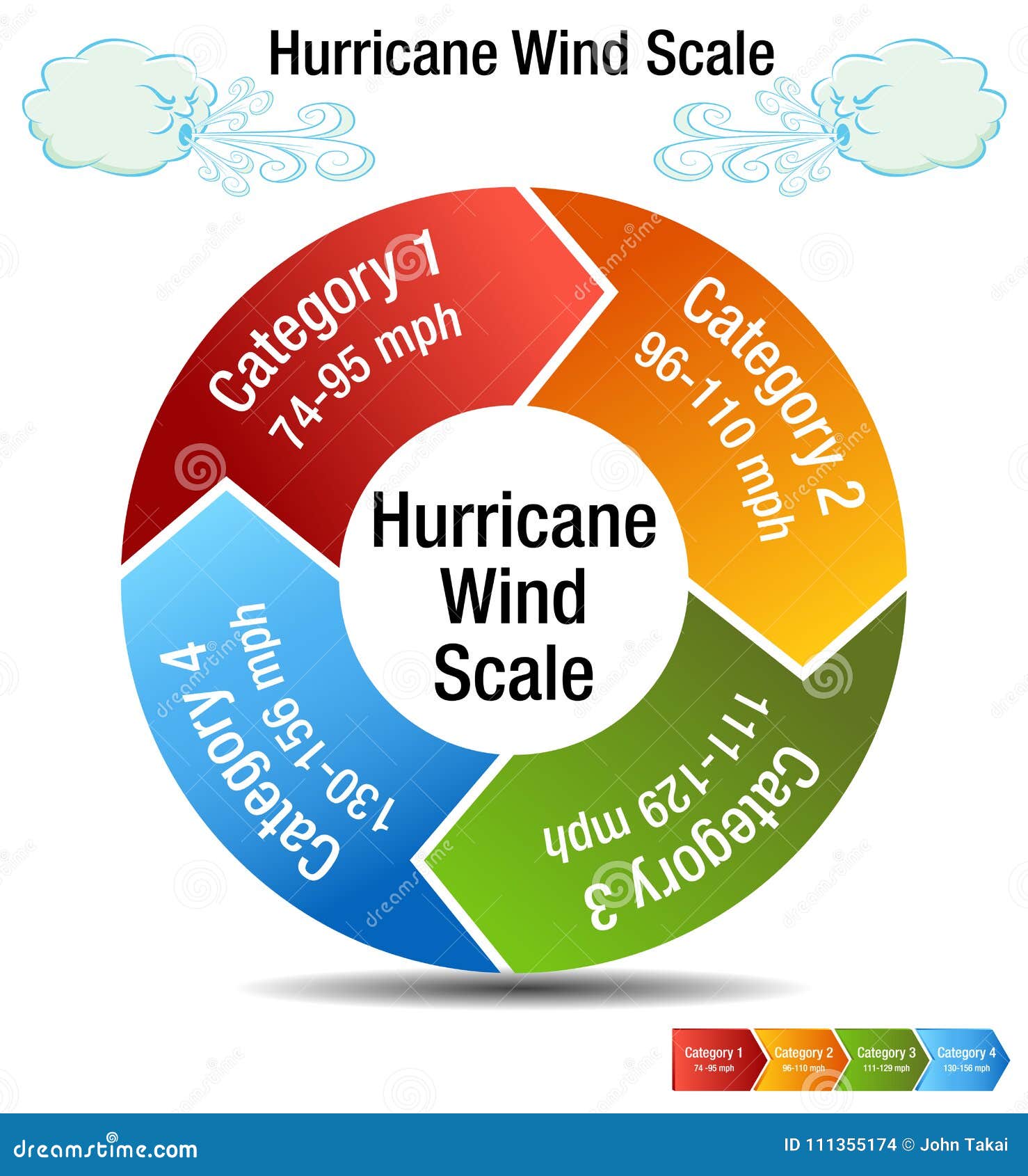

Category 1: 74-95 mph. Dangerous winds. You’ll lose some roof shingles. Vinyl siding might peel off. Tree branches snap. Power lines go down. It sounds manageable until a pine tree is through your roof.

Category 2: 96-110 mph. Extremely dangerous. You’re looking at major roof and siding damage. Shallow-rooted trees get uprooted. Near-total power loss for days or weeks.

Category 3: 111-129 mph. This is where the National Hurricane Center starts using the term "Major Hurricane." Devastating damage. Even well-built frame homes might lose their roof decking. Electricity and water could be gone for weeks.

Category 4: 130-156 mph. Catastrophic. Most of the roof structure will be gone on smaller homes. Most trees will be snapped or uprooted. Isolation is real because fallen trees and power poles block every single road.

💡 You might also like: Wisconsin Judicial Elections 2025: Why This Race Broke Every Record

Category 5: 157 mph or higher. The "Godzilla" tier. Total roof failure. Walls collapse. High-rises get their windows blown out. It’s basically unlivable for months.

Why the Chart Can Be Deceptive

If you only look at the numbers, you might think a 70 mph tropical storm is "safe" compared to a Category 1. It isn't.

Remember Hurricane Florence in 2018? By the time it hit North Carolina, it had "weakened" to a Category 1. People saw the hurricane wind speed chart drop and relaxed. That was a mistake. Florence crawled. It sat over the coast and dumped trillion of gallons of water. The wind didn't kill most people; the water did.

The Saffir-Simpson scale used to include pressure and storm surge estimates. They actually stripped those out around 2010. Why? Because the correlation wasn't perfect. You can have a huge, sprawling Category 2 storm that pushes way more water than a tiny, pin-hole Category 4.

The scale is an estimate of wind damage to property. It is not a "danger meter" for your life.

The Physics of Wind: Why 10 mph Matters

Wind force doesn't grow in a straight line. It's exponential.

If the wind speed doubles, the force on your house quadruples. A 100 mph wind is not just "a bit worse" than a 50 mph wind. It is significantly more violent. This is why the jumps between categories on the hurricane wind speed chart feel so dramatic.

📖 Related: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

When you get into Category 3 territory, the air starts behaving like a solid object. It picks up gravel, roof tiles, and lawn furniture, turning them into high-velocity bullets. An oak tree that stood for eighty years can be twisted out of the ground in seconds because the soil gets saturated and the wind leverage is just too much.

Real World Examples of Scale Failure

Let’s talk about Sandy in 2012. Technically, it wasn't even a hurricane when it hit New Jersey and New York—it was a "post-tropical cyclone." If you were just looking for a hurricane rank, you would have missed it.

But Sandy was massive. It was over 900 miles wide. It pushed a wall of water into Manhattan. The "wind speed" was relatively low, but the impact was billions of dollars in damage and dozens of lives lost.

Contrast that with Hurricane Charley in 2004. Charley was a tiny, tight ball of fury. It was a Category 4. If you were ten miles away from the eye wall, you barely got a breeze. If you were in the eye wall, your house was gone.

The hurricane wind speed chart tells you the intensity of the core, but it says nothing about the size of the field. A giant Category 2 is often scarier than a tiny Category 4.

How to Actually Use This Information

When the NHC (National Hurricane Center) puts out a forecast, look at the "Cone of Uncertainty" and the wind field graphics, not just the category number.

- Check the wind field size. Is the storm 50 miles wide or 400?

- Look at the forward speed. Is it moving at 20 mph or 5 mph? Fast storms bring wind; slow storms bring floods.

- Ignore the "it's only a Category 1" talk. If you live in a mobile home, a Category 1 is a death trap. If you live in a coastal flood zone, the wind speed is secondary to the surge.

The Problem With "Category 6"

Every few years, someone suggests adding a Category 6 to the hurricane wind speed chart. They point to storms like Patricia (2015) which had winds of 215 mph.

👉 See also: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

Scientifically, it makes sense. If the categories are about damage, what is the word for "more than catastrophic"? But the NHC has resisted this. Their logic is pretty sound: once a house is destroyed at 160 mph, it doesn't really matter if the wind is 200 mph. It’s already gone. Adding more numbers might actually make people less likely to take a Category 5 seriously.

Practical Steps for the Next Season

Don't wait for the tropical wave to become a depression before you act.

First, find your evacuation zone. This is usually based on elevation and surge risk, not just wind. If your local government says go, you go. They aren't looking at the wind speed; they’re looking at the water.

Second, harden your home. Impact-resistant windows or actual plywood shutters make a massive difference. Once the wind gets inside your house, the pressure change can literally lift your roof off from the inside out. It's called "internal pressurization," and it’s how most homes are lost in Category 3+ storms.

Third, get a battery-powered radio. When the cell towers go down—and they will in a Category 2 or higher—your fancy weather app is a brick.

Finally, understand that the hurricane wind speed chart is just a tool. It’s one piece of a puzzle that includes rainfall, surge, and duration. Treat every hurricane as a flood event first and a wind event second. You can hide from wind, but you have to run from water.

Check your insurance policies now. Standard homeowners insurance almost never covers "rising water" (flood). It covers "falling water" (rain coming through a hole in the roof). If you’re waiting for a storm to form before buying flood insurance, you’re usually too late—there’s often a 30-day waiting period.

Stay safe, watch the pressure drops, and remember that the numbers on the screen are just the beginning of the story.

Next Steps for Preparation:

- Locate your home’s elevation relative to the nearest body of water to understand your specific surge risk.

- Inventory your property using video or photos and upload them to a cloud service immediately.

- Review the NHC’s "Arrival of Tropical-Storm-Force Winds" graphics instead of just the eye’s path, as these indicate when it becomes too dangerous to continue outdoor preparations.