If you spent any time on social media during the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season, you probably saw them. Bright, chaotic tangles of lines zig-zagging across a map of the Gulf of Mexico or the Florida coast. They look like someone dropped a bowl of neon pasta on a chart. We call them hurricane spaghetti models 2024, and honestly, they are one of the most misunderstood tools in meteorology. People see a single line crossing their house and panic. Or, they see a line 50 miles away and think they’re safe. Both reactions are usually wrong.

Weather forecasting isn't a crystal ball. It’s math. It’s physics.

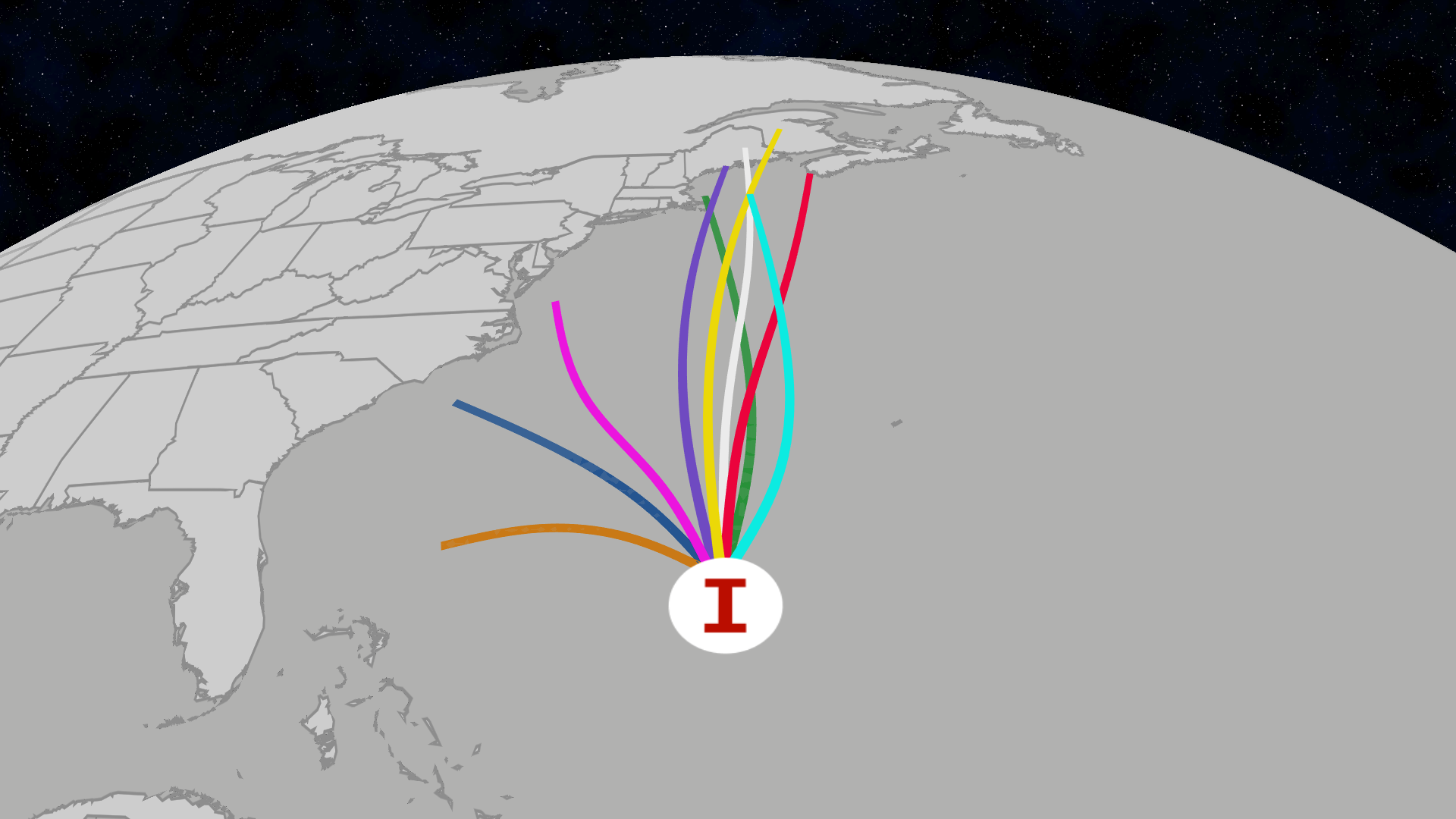

The 2024 season was particularly weird. Remember Beryl? It was the earliest Category 5 hurricane on record. It defied a lot of the early logic. When we look at hurricane spaghetti models 2024, we aren't looking at "the path." We are looking at a collection of possibilities. Each line represents a different computer model’s "best guess" based on a slightly different set of initial conditions. If the lines are tightly packed, meteorologists feel confident. If they look like a spider on caffeine, we have a problem.

Why the Lines Don't Always Agree

Every model has a personality. Some are better at handling the upper-level winds. Others focus more on sea surface temperatures. You’ve probably heard of the "GFS" (the American model) and the "European" (ECMWF). During 2024, these two were often at odds, especially during the development of Hurricane Milton.

The GFS tends to be a bit more "jumpy." It reacts quickly to new data, which sometimes makes it look like it's chasing its tail. The European model is usually more stable, but it isn't perfect. In the context of hurricane spaghetti models 2024, these global models are just the starting point. Then you have the "convection-allowing" models like the HWRF or the HMON. Those are the ones that try to figure out the internal structure of the storm. Will the eye wall collapse? Is it going to undergo rapid intensification?

The Difference Between Global and Mesoscale

It’s basically a matter of resolution. Think of a global model like a satellite photo of a whole state. You see the big stuff—the mountains, the coastline. But a mesoscale model is like a drone flying over your neighborhood. It sees the trees and the street signs. When you see a spaghetti plot, you’re often seeing a mix of both. Mixing them is helpful, but it's also why the lines diverge so wildly once you look five days out into the future.

💡 You might also like: The Cannibal Cop New York Case: Why This Disturbing Story Still Challenges Our Legal System

The 2024 season was defined by record-breaking ocean heat. The "Main Development Region" (MDR) was hot. Like, bathtub hot. This heat acted as high-octane fuel. When the water is that warm, even a weak disturbance can turn into a monster overnight. This makes the hurricane spaghetti models 2024 even harder to read because the models sometimes struggle to predict exactly when a storm will "decouple" from the environment and start creating its own weather.

Reading the "Ensemble" Instead of the Line

Most people don't realize that "spaghetti" usually refers to an ensemble. Take the GFS ensemble, or GEFS. Forecasters take the GFS model and run it 30 different times. Each time, they change the starting data by a tiny, tiny amount. Maybe they change the temperature in the Caribbean by half a degree. Maybe they nudge the wind speed in the Sahara Desert.

If all 30 runs end up in the same place, that's a high-confidence forecast.

But in 2024, we saw plenty of "split" ensembles. Half the lines would go toward Louisiana, and the other half would curve toward Florida. This is what we call a bifurcated track. For a homeowner in Tampa, seeing that "spaghetti" is terrifying because it offers no certainty. But for a professional forecaster at the National Hurricane Center (NHC), it's a signal to tell the public: "The uncertainty is very high. Do not focus on the center line."

The NHC actually creates their "cone of uncertainty" based on historical error, not just the spaghetti models. They know that, on average, they’re going to be off by a certain number of miles. The cone is designed to contain the actual center of the storm about two-thirds of the time. That means one out of three times, the storm will actually go outside the cone.

The 2024 Reality Check: Milton and Helene

Let’s talk about Hurricane Helene. The hurricane spaghetti models 2024 for Helene were actually fairly consistent. They pointed toward the Big Bend of Florida pretty early on. But here is the catch: the spaghetti lines only show where the center of the storm goes. They don't show how wide the storm is.

Helene was massive.

👉 See also: Denver Migrant Shelter Closing: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Even if you were 200 miles away from the "line" on the spaghetti plot, you were getting hammered. The wind field was huge. The surge was catastrophic. This is the biggest danger of these models. They focus the human eye on a thin line, making people forget about the hundreds of miles of rain and wind surrounding that line.

Then came Milton. Milton was a "model breaker." It went from a tropical storm to a Category 5 in what felt like the blink of an eye. Some of the hurricane spaghetti models 2024 struggled to keep up with the pressure drops. When a storm intensifies that fast, its "steering" changes. A deeper, stronger storm is pushed by winds higher up in the atmosphere. A weaker, shallower storm is pushed by lower-level winds. If the model doesn't know how strong the storm is, it can't know which way the wind will push it.

Data Gaps and why they matter

We still have huge holes in our data. We don't have sensors every ten feet in the ocean. We rely on buoys, which are sparse, and "Hurricane Hunters"—those brave crews who fly planes directly into the eye. In 2024, the data from these flights was critical. When a plane drops a "sonde" (a sensor package) into the storm, the real-time data is fed back into the models. You can actually see the spaghetti models shift in real-time after a flight. It's wild. One flight can shift the entire consensus 50 miles to the east.

Don't Forget the "Model of the Day" Trap

There is a temptation for hobbyists to find the one model that "got it right" last time and treat it like gospel for the next storm. "Oh, the ICON model nailed the turn on Beryl, so I’m following the ICON for Debby."

Don't do that.

Models don't have "hot streaks." A model might perform well in one environment (like a low-shear environment in the deep Atlantic) and fail miserably in another (like a high-shear environment in the Gulf). The 2024 season proved this repeatedly. The European model, which is usually the gold standard, had some rough runs where it missed key turns that the GFS actually caught.

How to Actually Use This Information

If you are looking at hurricane spaghetti models 2024 or any future season, you need a strategy. Stop looking at the individual lines. Instead, look for the "envelope."

What is the furthest left line? What is the furthest right line? That entire area is your "threat zone." If you are inside that envelope, you need to be prepared. Also, check the timestamp. If you’re looking at a model run that is 12 hours old, it is basically trash. New data comes in at 00z, 06z, 12z, and 18z (Greenwich Mean Time). If you aren't looking at the most recent "initialization," you’re looking at old news.

The Role of Artificial Intelligence

2024 was also a breakout year for AI weather models like GraphCast and FourCastNet. These are different. They don't solve physics equations. Instead, they look at 40 years of historical weather data and say, "In the past, when the atmosphere looked like this, the storm went there." Interestingly, these AI models were often more accurate than the traditional supercomputer models during the 2024 season. It’s a bit controversial in the meteorology world, but the results are hard to ignore.

Actionable Steps for the Next Storm

When the next set of spaghetti models starts circulating on your feed, follow these steps to stay sane:

✨ Don't miss: The Miracle on the Hudson: What People Still Get Wrong About Flight 1549

- Check the source. If the map doesn't have a timestamp or a model name (like GEFS, EPS, or UKMET), ignore it. It’s probably "weather porn" designed for clicks.

- Focus on the consensus, not the outlier. There is always one "rogue" line that shows the storm hitting your house. Don't obsess over it. Look at where the thickest cluster of lines is located.

- Look for "Run-to-Run Consistency." If the models have pointed at the same spot for three days in a row, confidence is high. If they are jumping from Alabama to Florida every six hours, nobody knows what's happening yet.

- Ignore anything past Day 5. The physics just break down. A spaghetti model showing a land-fall 10 days out is basically a coin flip. It's interesting for a "heads up," but it is not a basis for evacuation.

- Wait for the NHC. The professionals at the National Hurricane Center spend their lives looking at these. They weigh the models, look at the satellite data, and listen to the pilots. Their official forecast is always more reliable than a raw spaghetti plot you found on a random website.

The hurricane spaghetti models 2024 taught us that while our technology is getting better, the ocean is getting more volatile. We have better tools, but the "target" is moving faster. Use the models as a guide, keep your supplies ready, and never bet your life on a single neon line on a map.