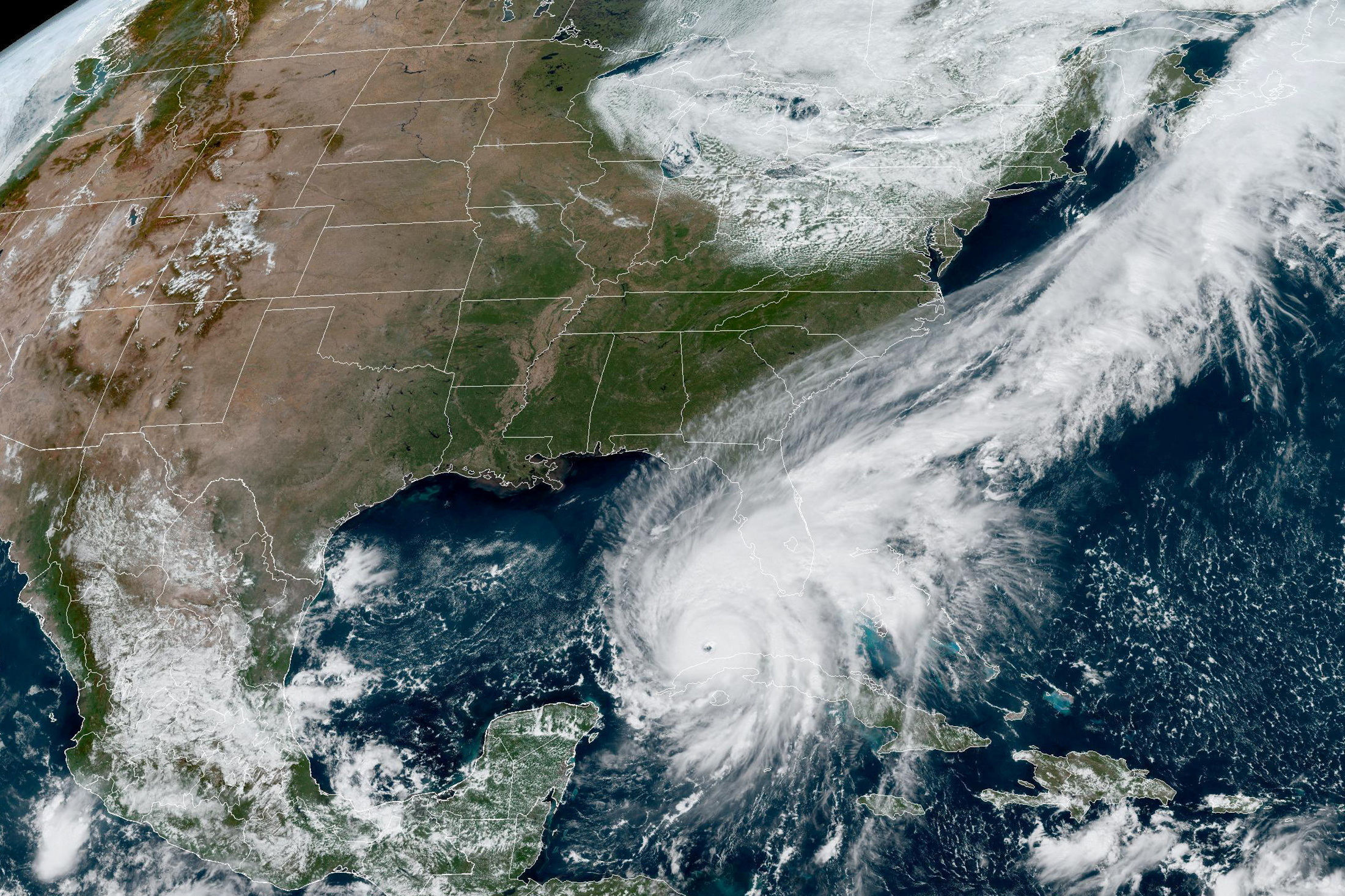

The wind starts as a whisper. Then, it’s a roar that sounds like a freight train parked in your front yard. If you live anywhere from the Florida Keys up to the rugged coast of Maine, a hurricane on east coast shores isn't just a weather event; it’s a seasonal anxiety that sits in the back of your mind from June to November. We've seen the satellite loops. We've watched the spaghetti models wiggle across our screens. But honestly, despite all the supercomputers at the National Hurricane Center (NHC) in Miami, these storms are becoming weirder, faster, and much more dangerous than they used to be.

It's not just your imagination.

Think back to Hurricane Sandy in 2012. It wasn't even a "major" hurricane by category standards when it hit New Jersey, yet it crippled New York City. Or look at Ian in 2022, which underwent what meteorologists call "rapid intensification." One minute it’s a manageable storm, the next it’s a Category 4 monster erasing coastal towns. The old rules—the ones our parents used to decide whether to stay or go—basically don't apply anymore.

The Warm Water Problem and Rapid Intensification

The engine of any hurricane on east coast tracks is the ocean. Specifically, the Gulf Stream. This river of warm water acts like high-octane fuel. Recently, sea surface temperatures in the North Atlantic have been hitting record highs, sometimes feeling more like a bathtub than an ocean. When a tropical wave moves over water that's $30°C$ or higher, it doesn't just grow; it explodes.

Meteorologists use the term "rapid intensification" to describe a jump in wind speed of at least 35 mph within 24 hours. It’s a nightmare for emergency planners. If a storm ramps up right before landfall, you don't have time to evacuate hundreds of thousands of people. You’re stuck. We saw this with Hurricane Idalia in 2023. It gained massive strength over the exceptionally warm waters of the Gulf before slamming into Florida’s Big Bend. The East Coast is just as vulnerable to this phenomenon, especially as those warm waters creep further north toward the Mid-Atlantic.

Why the "Category" Isn't Everything

We are obsessed with the Saffir-Simpson scale. Category 1, Category 5—we use these numbers to judge risk. But here’s the thing: the category only measures sustained wind. It tells you nothing about the size of the storm or the "wet" side of the danger.

- Storm Surge: This is usually what kills. It’s a wall of water pushed toward the shore by the force of the winds. In 2018, Hurricane Florence was "only" a Category 1 at landfall in North Carolina, but it moved so slowly and pushed so much water that it caused catastrophic flooding.

- Rainfall Totals: A slow-moving Tropical Storm can actually be more dangerous than a fast-moving Category 3. If a storm stalls, you’re looking at feet of rain, not inches.

- The Wind Field: A massive, sprawling storm like Sandy can have lower wind speeds but affect a much larger area, causing power outages for millions.

Focusing strictly on the "Cat" rating is a mistake. Honestly, it's a dangerous one.

Predicting the Path: Why the "Cone of Uncertainty" Fails You

You’ve seen the cone. That white, growing shape on the news that shows where the hurricane on east coast targets might be. Most people think the storm will stay inside the cone. That's not what it means. The cone represents where the center of the storm might go, based on historical forecast errors.

It doesn't show where the rain will fall. It doesn't show where the tornadoes will spin up. In fact, some of the worst damage often happens far outside that cone. Dr. Rick Knabb, a former director of the NHC, has spent years trying to get people to look at "impact maps" instead of just the track. If you’re on the "dirty side" of the storm—the front-right quadrant—the winds and surge are significantly worse because the storm’s forward motion adds to the wind speed.

The Jet Stream and the "Turn"

What actually moves these storms? It’s not just their own power. They are steered by large-scale atmospheric currents. Usually, a hurricane on east coast paths are dictated by the Bermuda High. If that high-pressure system is strong and sits over the Atlantic, it pushes storms toward the coast. If it’s weak, the storms often curve safely out to sea.

Then you have the Jet Stream. This river of air in the upper atmosphere can either "shear" a storm apart—literally blowing the top off it—or it can act as an exhaust pipe, helping the storm breathe and grow stronger. When a hurricane interacts with a dip in the Jet Stream (a trough), it can get pulled inland or accelerated north at 50 mph. This is why New England gets hit. People forget that Long Island and Rhode Island are hurricane magnets. The 1938 "Long Island Express" moved so fast that people didn't even know it was coming until the ocean was in their living rooms.

Infrastructure: The East Coast's Weakest Link

We have built too much, too close to the water. It's that simple. From the high-rises of Miami to the historic homes of Charleston and the refineries in New Jersey, the East Coast is a trillion-dollar target.

The Power Grid

Our grid is incredibly fragile. Most lines are above ground. A few falling branches can knock out power for a week. When a hurricane on east coast cities hits, it’s not just the wind; it’s the salt spray. Saltwater conducts electricity. It fries transformers. It corrodes components that weren't meant to be submerged.

The Drainage Problem

In places like Norfolk, Virginia, or Miami Beach, "sunny day flooding" is already a thing. High tides now spill into the streets because of sea-level rise. When you add a hurricane's rainfall and storm surge to that already high baseline, the water has nowhere to go. The pumps can't keep up. The soil is already saturated. You get inland flooding that lasts for weeks, long after the sun comes back out.

What Most People Get Wrong About Preparedness

"I'll just wait and see."

That’s the most common phrase heard in coastal bars and grocery store aisles. It’s also the most dangerous. Waiting until the hurricane watches are issued means you’re fighting for the last gallon of milk and the last sheet of plywood.

You need to understand your "Vulnerability Profile." Do you live in an evacuation zone? This isn't about how strong your house is; it’s about whether the roads will be underwater when you try to leave. If the local authorities tell you to go, you go. They aren't worried about your roof blowing off; they’re worried about the 10 feet of water that will prevent ambulances from reaching you when you have a medical emergency.

The Real Survival Kit

Forget the fancy gear. You need the basics, but you need them in a way that actually works when the world turns upside down.

- Cash is King: When the power goes out, credit card machines don't work. ATMs don't work. You need small bills.

- The Paper Map: Your phone's GPS is great until the cell towers are blown over or the network is jammed. Have a physical road atlas of your state.

- Water Storage: You need one gallon per person per day. But don't forget your pets. And don't forget water for flushing toilets if you’re on a well (no power = no well pump).

- Prescriptions: Get a two-week supply of your meds before the storm even enters the Caribbean.

Looking Ahead: The Future of East Coast Storms

The data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) suggests we might not see more hurricanes, but the ones we do see will likely be more intense. We are looking at a future with more Category 4 and 5 storms. We are looking at storms that carry more moisture—roughly 7% more water vapor for every degree of warming.

This means the "inland flooding" threat is going to eclipse the "wind" threat for many people. If you live 100 miles inland, you aren't safe. You might not get the surge, but you could get the 20 inches of rain that turns your local creek into a river.

Actionable Steps for the Next Season

Don't wait for a name to be assigned to a tropical wave. Take these steps now to ensure you aren't part of the chaos when a hurricane on east coast alerts start popping up on your phone.

🔗 Read more: Trump We Love You God: Why This Slogan is Taking Over Rallies

Review Your Insurance Policy Today

Standard homeowners insurance does not cover flood damage. There is usually a 30-day waiting period for a National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) policy to kick in. If you wait until a storm is in the Atlantic, it's too late to buy coverage. Check your windstorm deductible too; it's often a percentage of your home's value, not a flat dollar amount.

Document Your Assets

Walk through your house with a phone and record a video of every room. Open the drawers. Show the electronics. If you have to file a claim later, having video proof of what you owned makes the process infinitely easier. Upload this video to the cloud immediately.

Hardening Your Home

You don't need a total remodel. Small things help. Impact-rated garage doors are huge—if the garage door fails, the pressure change can literally blow the roof off your house from the inside out. Clean your gutters. Trim the dead limbs off that oak tree hanging over your bedroom.

Establish a "Communication Trigger"

Decide now what your "go" point is. Maybe it’s when the storm reaches a certain latitude, or when a mandatory evacuation is issued for the county south of you. Having a pre-set trigger removes the emotion and indecision from the moment. When the trigger is hit, you execute the plan. No arguments. No "waiting to see the next local news update."

The East Coast is a beautiful place to live, but it comes with a price. Respecting the power of these systems means moving past the hype and focusing on the cold, hard reality of tropical meteorology. Stay informed, stay prepared, and never underestimate the water.