It was September 18, 1989. For many people in Puerto Rico, the day started with a weird, heavy stillness. You know that kind of humidity that feels like a wet wool blanket? That was it. But by the time the sun went down, the island was screaming. Hurricane Hugo Puerto Rico wasn't just a storm; it was a total cultural and physical reset for anyone living there. Honestly, if you talk to any local who was around back then, they don't talk about "the hurricane." They talk about Hugo. It’s the benchmark. Everything is either "before Hugo" or "after Hugo."

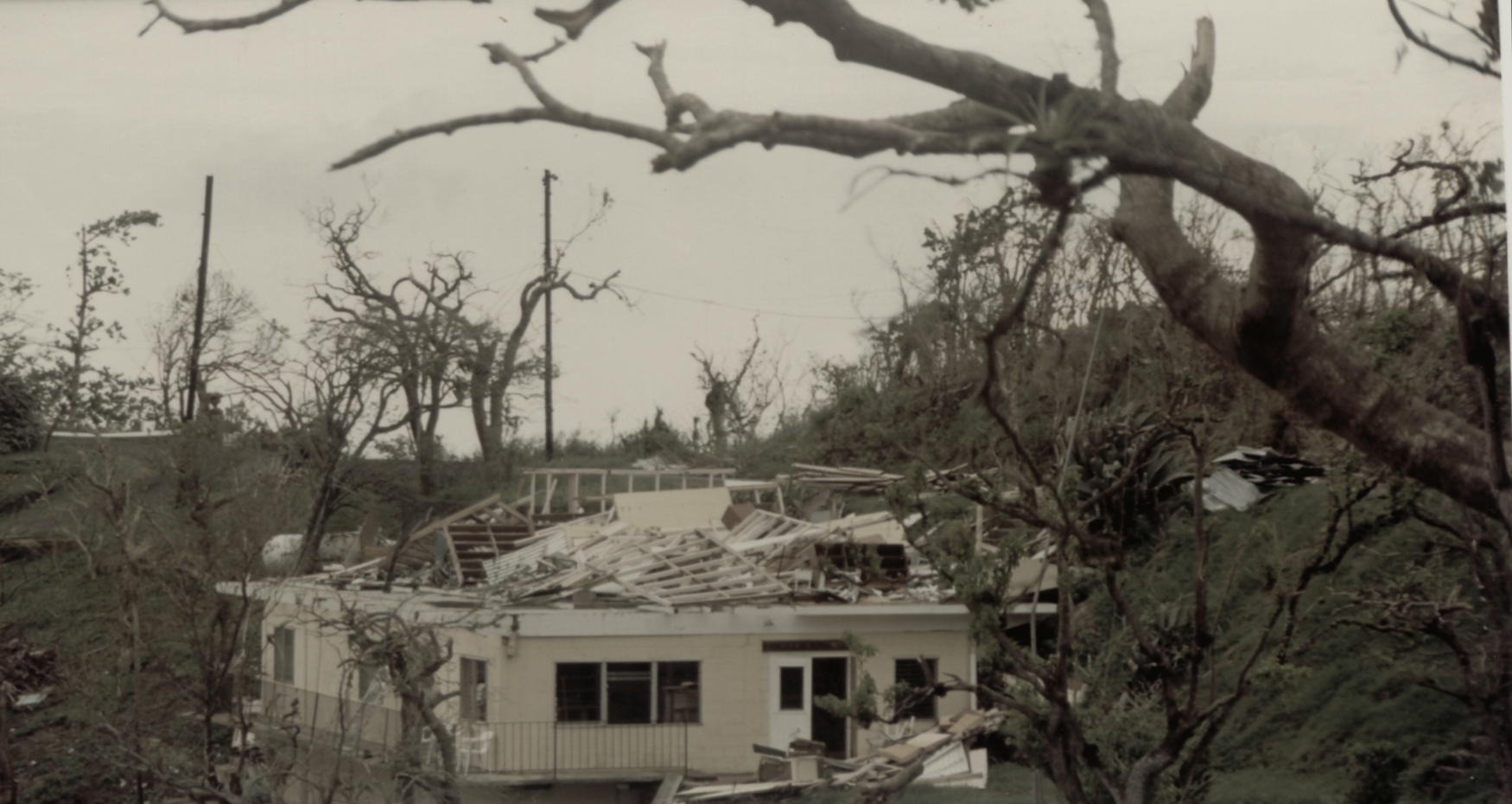

The storm hit as a Category 4. It wasn't some distant threat that grazed the coast. It tore through the northeastern corner of the island, specifically targeting places like Vieques, Culebra, and Fajardo with a violence that hadn't been seen in generations. People weren't ready. Not really. Back then, we didn't have iPhone alerts or real-time satellite feeds in our pockets. We had the radio, some plywood, and a lot of hope that turned out to be insufficient.

The Night the Lights Stayed Out

Hugo made landfall with sustained winds of about 140 mph. That’s fast. Like, "ripping the concrete off a balcony" fast. Most of the damage happened because the storm moved relatively slowly over the land, grinding down structures like a giant serrated knife.

The power grid basically vanished.

Think about that for a second. It wasn't just a few flickers. The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority (PREPA) saw its infrastructure shredded. High-voltage towers were twisted into metal pretzels. In San Juan, the capital, windows in high-rise hotels were popping out like champagne corks. If you were in a wooden house in the mountains, you were basically sitting in a tinderbox.

One of the most terrifying things about Hurricane Hugo Puerto Rico was the sound. Survivors describe it as a freight train that never ends. It’s a low-frequency roar that vibrates in your chest. When the eye passed over, there was that deceptive, eerie silence—people actually walked outside to check their roofs—only for the "dirty" side of the storm to slam them from the opposite direction minutes later. It was a trap.

Why Vieques and Culebra Got It Worst

The offshore islands of Vieques and Culebra were the first to take the hit. They were the "canaries in the coal mine," but nobody could hear them. Communications were cut almost instantly. For days, the main island didn't even know if people over there were still alive.

🔗 Read more: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

- The storm surge reached 7 to 8 feet in some areas.

- Nearly 80% of the wooden structures on Culebra were leveled.

- The vegetation was literally stripped of its bark. The islands went from lush green to a bruised, skeletal brown overnight.

The Federal Response (Or Lack Thereof)

Here is where things get messy and, frankly, a bit frustrating to look back on. FEMA wasn't the massive machine it is today. In 1989, the response to Hurricane Hugo Puerto Rico was criticized as being sluggish and disorganized. It took days for significant aid to reach the hardest-hit rural areas.

Then-Governor Rafael Hernández Colón had to mobilize the National Guard to prevent looting, which did happen in some areas of San Juan where desperation set in. People were hungry. They were thirsty. The water pumps didn't work without electricity. If you didn't have a cistern or a "tankey," you were hiking to a mountain stream with a bucket.

Actually, Hugo was a massive wake-up call for the United States. It happened right before Hurricane Andrew hit Florida in '92, and the failures in Puerto Rico actually served as a grim blueprint for what not to do. It’s weird to think about, but the suffering in Fajardo and Luquillo eventually led to better disaster management protocols for the entire mainland US.

The Economic Scars and the "Hugo Effect"

The numbers are staggering, even by today's inflated standards. We're talking about over $1 billion in damage in 1989 dollars. If you adjust that for 2026, it's astronomical.

Agriculture was wiped out. The coffee plantations in the center of the island? Gone. Banana trees? Snapped like toothpicks. It takes years for a coffee tree to produce a viable crop, so the farmers didn't just lose their harvest; they lost their livelihood for the next half-decade.

But there’s a nuance here that most history books skip. Hugo changed how Puerto Ricans built their homes. Before 1989, many houses were still "mixtas"—concrete first floors with wooden second stories. Hugo proved that wood didn't stand a chance. After the storm, there was a massive shift toward "cemented" living. Puerto Rico became a fortress of reinforced concrete. If you wonder why the island looks the way it does today—blocky, gray, and sturdy—you can thank Hugo.

💡 You might also like: Trump New Gun Laws: What Most People Get Wrong

Myths vs. Reality

A lot of people think Hugo was the deadliest storm. It wasn't. While the destruction was immense, the death toll in Puerto Rico was relatively low (around 12 directly attributed deaths) compared to the thousands lost in San Ciriaco in 1899 or the tragedy of Maria in 2017.

Why? Because Puerto Ricans are resilient as hell. They knew how to hunker down. But Hugo was the storm that taught the island about the "long tail" of a disaster. It wasn't the wind that killed people later; it was the lack of clean water, the lack of medicine, and the sheer exhaustion of living in the dark for six months.

I remember stories of families sharing a single small generator, daisy-chaining extension cords across three houses just to keep a few refrigerators running so the milk wouldn't spoil. That "comunidad" spirit grew out of the Hugo wreckage.

Modern Lessons from a 1989 Storm

If you’re looking at Hurricane Hugo Puerto Rico as just a history lesson, you're missing the point. It’s a case study in infrastructure fragility.

- Grid Vulnerability: Hugo proved that a centralized power grid is a liability on a tropical island. Decades later, the island is still struggling with this exact same issue.

- Communication is Life: When the towers go down, the government loses its ability to govern. Satellite tech has helped, but the physical copper lines of 1989 were a total failure point.

- The "Slow" Disaster: The week after the storm is always more dangerous than the four hours of the storm itself.

What You Should Do Now

If you live in a hurricane-prone area or are planning to move to the Caribbean, Hugo’s legacy offers some very practical, non-negotiable takeaways. Forget the "emergency kits" that just have a flashlight and some Band-Aids.

First, you need a redundant water system. A cistern isn't a luxury; it’s a requirement. Hugo taught us that the government cannot get water to everyone when the roads are blocked by downed trees and landslides.

📖 Related: Why Every Tornado Warning MN Now Live Alert Demands Your Immediate Attention

Second, look at your roof. Hugo peeled back corrugated metal like it was tin foil. If you have a "zinc" roof, it needs to be bolted, not nailed.

Third, understand your "zone." The people who fared best during Hugo weren't necessarily the ones with the most money; they were the ones who understood the topography of their land. They knew where the mud would slide and where the wind would tunnel.

The story of Hurricane Hugo Puerto Rico is ultimately one of survival and a very harsh education in tropical reality. It wasn't the first major storm, and as we've seen recently, it certainly wasn't the last. But it was the one that broke the old world and forced the new one to be built of concrete and iron.

Actionable Insights for Disaster Readiness:

- Audit your structural fasteners: Ensure your roof-to-wall connections use hurricane straps or clips rather than just gravity and nails.

- Invest in a solar-plus-battery setup: Relying on the centralized grid in Puerto Rico (or any island) is a gamble that history shows you will eventually lose.

- Document everything now: Survivors of Hugo struggled with insurance claims because they had no "before" photos. Take a video of every room in your house and upload it to the cloud today.

- Keep a paper map: When GPS fails because the cell towers are down, you need to know the backroads to the nearest hospital or distribution center.

Hugo was a beast. It changed the landscape, the laws, and the lives of millions. By respecting its history, you're better prepared for whatever the Atlantic decides to throw next.