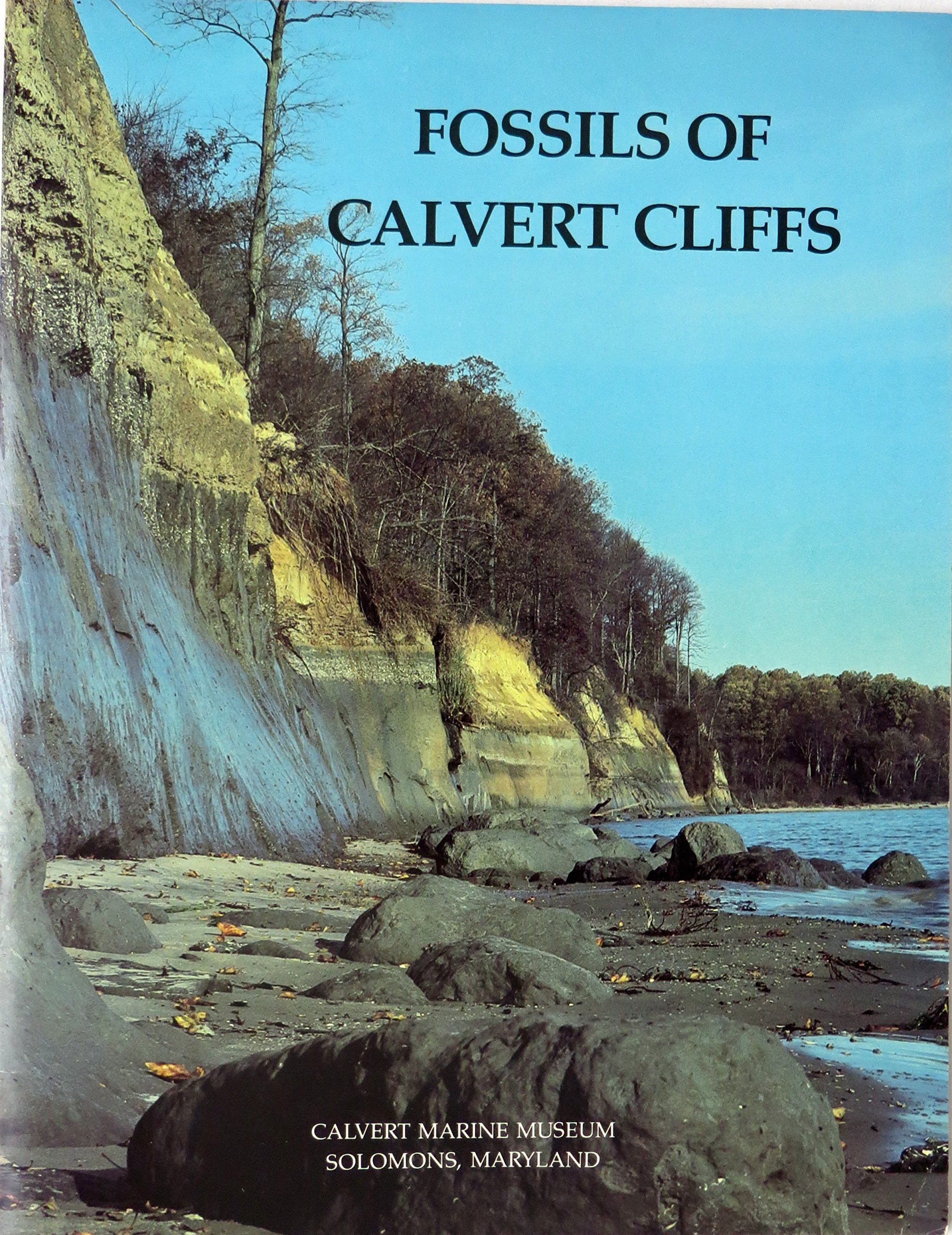

You're standing on a narrow strip of sand in Maryland, the Chesapeake Bay lapping at your ankles, and honestly, it’s easy to forget you’re walking on a graveyard. Not a spooky one. A massive, underwater one from 10 to 20 million years ago. These massive golden-brown walls of earth known as the Calvert Cliffs stretch for about 24 miles along the western shore of the Bay. They aren't just scenic overlooks for hikers; they are literally made of ancient seafloor. If you look closely at the base of the cliffs after a good storm, you might see the serrated edge of a tooth that belonged to a predator twice the size of a school bus.

Fossils of Calvert Cliffs aren't just a niche hobby for geology nerds. They are a global phenomenon. Scientists from the Smithsonian and the Calvert Marine Museum have been pulling treasures out of this silt since the 19th century. But here’s the thing: you don't need a PhD to find them. You just need a pair of sharp eyes and a little bit of patience.

Most people come here looking for one thing. The Megatooth. Otodus megalodon. It’s the "holy grail" of the cliffs. While those six-inch monsters are rare, the sheer volume of other life preserved here is staggering. We’re talking over 600 species identified so far. From prehistoric crocodiles to microscopic foraminifera, the cliffs are a vertical timeline of the Miocene Epoch.

Why the Miocene Matters (And Why It’s Under Your Feet)

The Miocene was a weird time for the Mid-Atlantic. The Earth was generally warmer, and the polar ice caps were smaller than they are today. Consequently, the ocean level was much higher. Most of what we now call Southern Maryland was submerged under a shallow, temperate sea known as the Salisbury Embayment.

Think of it like a giant ecological mixing bowl.

Because the water was shallow and nutrient-rich, life exploded. When these animals died, they sank into the soft, oxygen-poor mud. That’s the secret sauce for preservation. The lack of oxygen prevented bacteria from completely breaking everything down, and the heavy silt layers protected the bones from being crushed or scattered by currents. Over millions of years, the land rose, the waters receded, and the wind and rain began carving into the sediment.

Today, the cliffs erode at a rate of about one to two feet per year. Every time a chunk of the cliff falls, new fossils are exposed. It’s a literal conveyor belt of prehistory.

📖 Related: The Gwen Luxury Hotel Chicago: What Most People Get Wrong About This Art Deco Icon

The Predators You’ll Actually Find

Let's be real: everyone wants the Megalodon tooth. It’s iconic. But if you go expecting a hand-sized tooth on your first trip, you're probably going to leave disappointed. What you will find are the teeth of its cousins.

The most common finds are Snaggletooth shark teeth (Hemipristis serra). You can recognize them by their distinctively "hooked" shape and chunky serrations. Then you have the Carcharhinid family—Requiem sharks. These are the ancestors of modern Bulls, Lemons, and Tigers. They are usually small, triangular, and sharp as a razor. Honestly, once you train your eyes to see the "black shine" of fossilized enamel against the dull tan of the pebbles, you’ll start seeing them everywhere.

It’s Not Just Sharks

While the sharks get the headlines, the fossils of Calvert Cliffs tell a much broader story.

- Whales and Dolphins: The Salisbury Embayment was a nursery for cetaceans. It is incredibly common to find "ear bones" (periotics) or vertebrae. These fossils are often heavy and dense, feeling more like stone than bone because of the mineralization process.

- Ray Plates: Ever find a flat, rectangular black rock with ridges on it? That’s probably a mouth plate from a prehistoric stingray. They used these to crush shells, sort of like a biological nutcracker.

- Turritella and Mollusks: Some layers of the cliff are packed so tightly with shells that there’s more shell than dirt. The spiral-shaped Turritella snails are a favorite for kids because they look like little stone screws.

- Crocodilians: Yes, there were massive crocodiles in Maryland. Finding a Thecachampsa tooth is a major win. They look like dark, pointed pegs, quite different from the flat blades of a shark.

The Danger Nobody Talks About (Seriously)

I need to be very clear about this: the cliffs are dangerous. This isn't just "lawyer talk." People have died here. The sediment is remarkably unstable, consisting of compacted clay and sand that can fail without warning.

A "slump" can happen on a perfectly sunny day. Thousands of pounds of earth can drop in a second. Because of this, it is strictly illegal to dig into the cliffs or even stand too close to the base in most areas. The best way to find fossils—and the only legal way in most parks—is to search the "wash" where the tide has already done the work for you.

The best time to go is right after a storm or during a low tide following a period of high wind. The waves act like a giant sieve, pulling the lighter sand away and leaving the heavier fossils behind on the shoreline.

👉 See also: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

Where to Actually Go

You can't just pull over on the side of the road and jump into the Bay. Much of the shoreline is private property. If you want to legally find fossils of Calvert Cliffs, you have a few primary options:

Calvert Cliffs State Park is the big one. It requires a nearly two-mile hike through the woods to reach the beach, which keeps the crowds somewhat thin. The "Red Trail" is the standard route. It’s a bit of a trek, but the reward is a massive stretch of beach where you can sift to your heart's content.

Brownies Beach (Bay Front Park) used to be the go-to spot for locals, but check the current regulations before you head out. In recent years, access has been restricted to local residents during peak seasons due to overcrowding. If you can get in, it’s famous for having a high concentration of smaller shark teeth.

Flag Ponds Nature Park is arguably the best for families. It has a shorter walk than the State Park and offers great amenities. The fossil beds here are productive, and the scenery is top-tier.

Identifying Your Finds

So you found something black and shiny. Now what?

Fossilized teeth in this region are almost always black, dark grey, or deep brown. This is due to the phosphate in the sediment replacing the calcium in the tooth over millions of years. If it’s white, it’s probably modern. If it’s porous like a sponge, it’s bone. If it’s dense and smooth, it’s likely enamel.

✨ Don't miss: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

A lot of people mistake pieces of "ironstone" for fossils. Ironstone is a natural rock formation that can take on weird, bone-like shapes. The "lick test" is an old geologist trick—if you touch your tongue to it and it sticks a little, it’s likely fossilized bone. If it doesn’t, it’s probably just a rock. Maybe don't do that if the beach is particularly crowded, though. It looks a little weird.

For serious identification, the Calvert Marine Museum in Solomons is the gold standard. They have world-class exhibits and staff who can help you identify that weird lump you found. They even have a "fossil club" for the truly obsessed.

The Ethics of Fossil Hunting

There is a bit of a debate in the paleontology world about "amateur" collectors. Some think every fossil belongs in a museum. Others recognize that without the thousands of hobbyists walking the beaches, most of these fossils would simply be ground into dust by the waves and lost forever.

The general rule of thumb is: if you find something articulated (bones still joined together) or something massive like a whale skull, don't move it. Mark the location, take photos, and call the Calvert Marine Museum. You might have just discovered a species new to science. If it’s an individual tooth or a fragment of rib bone, it’s yours to keep.

Actionable Steps for Your First Expedition

If you're planning to head out this weekend, don't just wing it. A little preparation goes a long way.

- Check the Tides: This is non-negotiable. If you go at high tide, there is no beach. Use a tide chart for "Cove Point" or "Solomons" and aim to arrive two hours before low tide.

- Bring a Sifter: You can buy a professional fossil sifter, but a kitchen colander or a frame made of 1/4 inch hardware cloth works just fine. Scooping up a handful of "shell hash" and shaking it out is way more effective than just looking at the surface.

- Sun Protection: There is zero shade on those beaches. The cliffs reflect the heat. You will cook if you aren't careful.

- Footwear: Wear shoes that can get wet. The "beach" is often a mix of sharp shells, slippery clay, and rocks. Flip-flops are a recipe for a twisted ankle.

- Storage: Bring small pill bottles or Tupperware. Fossil teeth are surprisingly fragile once they dry out, and you don't want to lose your best find through a hole in your pocket.

Hunting for fossils at Calvert Cliffs is a humbling experience. You’re picking up a piece of a world that existed long before humans were even a thought. It’s a tangible connection to deep time, and honestly, there’s nothing quite like the rush of seeing that black triangular shape sitting in the sand, waiting for someone to find it after 15 million years.

Next Steps for Your Search:

- Download a Tide App: Look for "Tides Near Me" and set your location to Lusby or Solomons, MD.

- Pack a "Fossil Kit": Include a small mesh sifter, a fanny pack for storage, and a magnifying glass for the tiny teeth.

- Visit the Calvert Marine Museum First: Seeing the "ideal" versions of these fossils in the museum will train your brain to recognize the fragments you'll see on the beach.

- Stay Low: Keep your eyes focused on the waterline where the waves are actively tumbling the gravel; this is where the freshest fossils are uncovered.