The headlines are enough to make anyone want to live in a bunker. Every time a new strain of avian influenza pops up in a dairy farm or a poultry plant, the same question starts trending: is this the one that finally jumps? We’ve been hearing about H5N1 for decades. It's the "wolf" in the "boy who cried wolf" scenario of public health. But lately, the tone has shifted. When we talk about human to human transmission of bird flu, we aren't just talking about a theoretical disaster anymore. We are looking at specific, documented instances where the virus tried to make the leap, and why it hasn't quite stuck the landing—yet.

It's scary. Honestly, it's okay to admit that.

But here is the reality: birds are the natural reservoir. They've had these viruses for millennia. For a bird virus to become a human virus, it has to undergo a sort of biological extreme makeover. It’s not just one mutation. It’s a series of "lucky" breaks for the virus that are very unlucky for us.

The Missouri Case and the Mystery of the "Silent" Spread

Most people think of bird flu as something you get from touching a sick chicken. That’s how it usually happens. You work on a farm, you breathe in some dust or get fluids on you, and you get sick. But in 2024, something happened in Missouri that made the CDC and the WHO lean in a little closer. A person was hospitalized with H5N1 who had no known contact with animals. No cows, no birds, no backyard coop.

Then, some of their close contacts and healthcare workers also got respiratory symptoms.

This is where the term human to human transmission of bird flu moves from the lab to the real world. If a person gets it without an animal source, and then the people around them get sick, that is the literal definition of a transmission chain. However, the Missouri case was frustratingly murky. By the time investigators got there, the window for perfect testing had narrowed. Blood tests eventually showed that some of those contacts had antibodies, but it wasn't the "smoking gun" that proves sustained, easy spread. It was more like a spark that didn't quite catch the forest on fire.

We’ve seen this before. Back in 1997 in Hong Kong, and in various clusters in Indonesia and Thailand over the years, small family groups have caught it from one another. It usually dies out after one or two people. Why? Because the virus is still "shaped" for a bird’s throat, not a human’s.

🔗 Read more: Why a Vitamins and Minerals Table Still Matters for Your Real-World Diet

Why the "Lock and Key" Mechanism Matters

Think of the virus like a key. Your cells have locks (receptors). Bird flu viruses are great at unlocking cells deep in the human lungs—the lower respiratory tract. That’s why it’s so deadly; it causes viral pneumonia. But to spread easily through coughing or sneezing, the virus needs to be able to unlock the cells in your nose and throat (the upper respiratory tract).

Right now, H5N1 and its cousins aren't very good at that. They are "sticky" in the lungs but "slippery" in the nose.

Scientists like Dr. Richard Webby at St. Jude Children's Research Hospital spend their lives watching for the specific mutations—like PB2 E627K—that allow the virus to replicate better at the cooler temperatures found in the human nose compared to the hot internal temperature of a bird. If the virus learns to live in the nose, it can hitch a ride on a sneeze. That’s the line we haven't seen it cross in a major way.

Is the Dairy Farm Outbreak a Game Changer?

The 2024-2025 H5N1 outbreak in US dairy cattle changed the conversation. Before this, we didn't really think of cows as a primary risk. But the virus moved into the udders. It showed up in high concentrations in raw milk. We saw farmworkers getting conjunctivitis—pink eye—after being splashed with milk.

This matters for human to human transmission of bird flu because every time the virus jumps into a mammal, it gets a "training session."

Mammals are more like us than birds are. If the virus adapts to spread between cows, or between pigs (which are the ultimate "mixing vessels"), it is essentially practicing for us. In October 2024, the CDC confirmed H5N1 in a pig in Oregon. This was a "wait, what?" moment for virologists. Pigs can be infected by both bird flu and human flu at the same time. Inside the pig, the two viruses can swap segments of their DNA. It’s called reassortment. It’s basically viral sex. If a human flu virus swaps its "ease of spread" gene with a bird flu’s "deadliness" gene, we have a massive problem.

What the Data Actually Says About Your Risk

Let's be blunt: your risk of catching bird flu from your neighbor today is effectively zero.

There is no evidence of "community spread." That is the phrase you want to listen for in the news. Community spread means the virus is circulating among people who haven't been to a farm or handled raw milk. If that happens, the CDC will be the first to scream it from the rooftops because they have a massive surveillance network of wastewater testing and flu-tracking apps.

- Wastewater monitoring: We are now tracking H5 markers in sewage. If a city starts showing high levels of H5 without a nearby poultry plant, it’s a red flag.

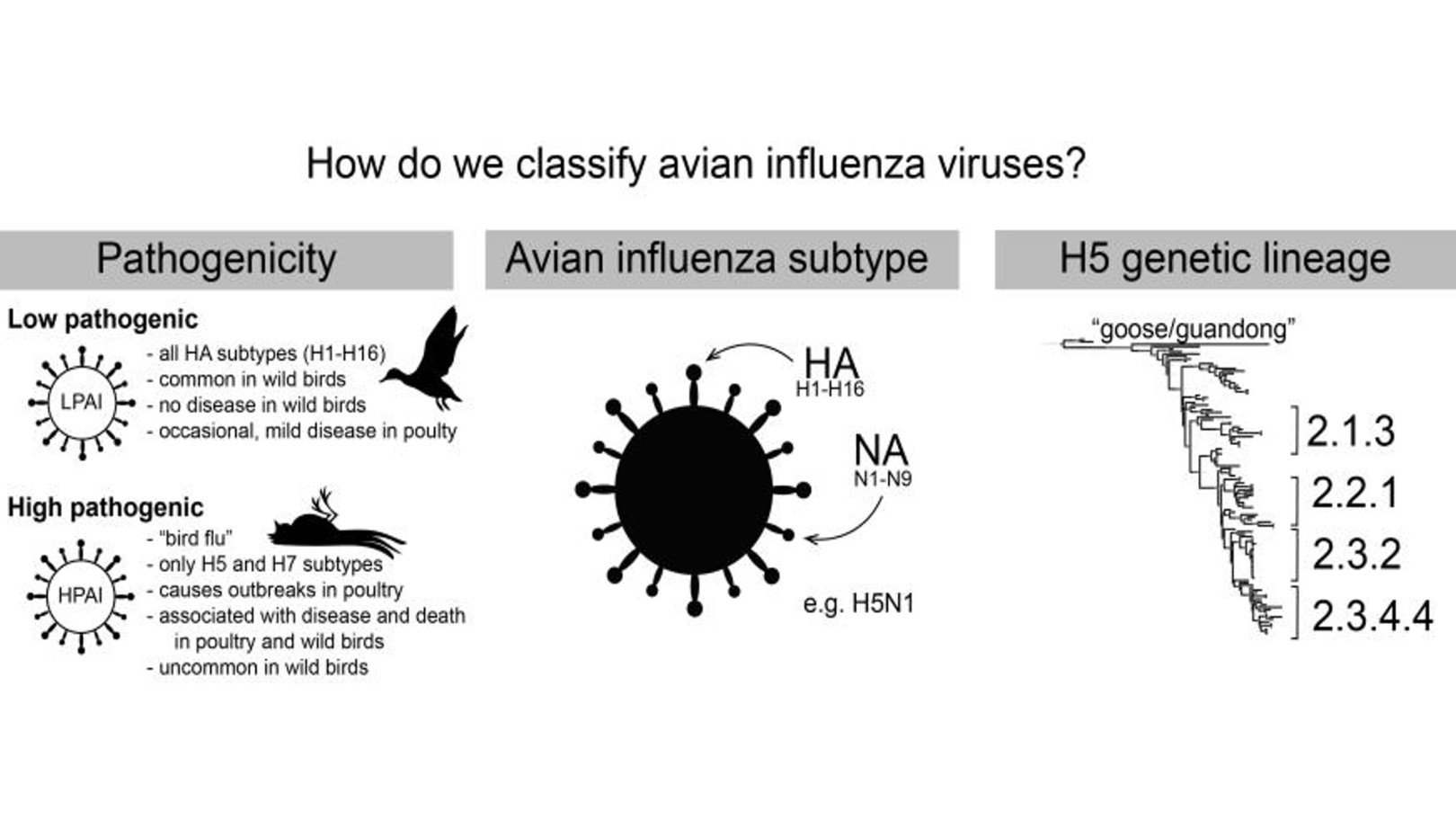

- Genetic Sequencing: Every time a human gets infected, the virus is sequenced immediately. Scientists look for "human-adapting" mutations in the HA (hemagglutinin) protein.

- Antiviral Sensitivity: So far, the strains we’ve seen are still mostly susceptible to Oseltamivir (Tamiflu). That's good news.

The mortality rate is often cited as being over 50%. That sounds terrifying. However, that number is likely skewed. It only counts the people who got so sick they went to a hospital and were tested. It doesn't count the farmworker who had a scratchy throat for two days and stayed home. The real "death rate" for humans is likely much lower, though still potentially much worse than the seasonal flu.

Why We Aren't in a Pandemic Yet

Biology is hard. For a virus to become a pandemic threat, it has to achieve a "fitness" balance. It has to be stable enough to survive in the air, sticky enough to grab human receptors, and efficient enough to hijack our cellular machinery to make copies of itself.

Usually, when a virus gains a mutation that makes it spread better, it loses some of its "virulence" (its ability to make you really sick). Evolution doesn't actually "want" to kill the host; it wants the host to walk around and sneeze on fifty other people. This is why many experts believe that if human to human transmission of bird flu becomes common, the virus might actually become less lethal in the process. Not a guarantee, but a common evolutionary trade-off.

The Role of Government and Vaccines

The US has a "seed" vaccine for H5N1. If the situation changed tomorrow, the government has the ability to start mass-producing shots tailored to the current strain. They’ve already started bottling some of this as a precaution. This isn't 2020; we aren't starting from scratch. We know what this virus looks like.

But public trust is at an all-time low. That's the real hurdle. If the CDC says "we need to vaccinate poultry workers," and half the workers refuse because of misinformation, the virus gets more chances to mutate. It’s a race between the virus’s ability to change and our ability to cooperate.

Practical Steps You Can Actually Take

You don't need to wear an N95 to the grocery store. Not for this, anyway. But you should be smart about where the virus currently lives.

👉 See also: Para qué es la hidrocortisona: verdades, errores comunes y lo que tu piel intenta decirte

Avoid Raw Milk. Honestly, just don't do it right now. Pasteurization kills H5N1. Raw milk is a direct path for the virus to enter your system. High-heat cooking also kills the virus in meat and eggs.

Don't Touch Dead Birds. If you see a dead crow or duck in your yard, don't pick it up with your bare hands. Call your local wildlife agency. They want to test those birds to see where the virus is moving.

Protect Your Pets. If you live in an area with a bird flu outbreak, keep your cats inside. Cats are actually very susceptible to H5N1 and can get severely ill after eating infected birds. There have been cases of cats passing it to humans in domestic settings, though it’s very rare.

Stay Informed, Not Panicked. Follow sources like the CIDRAP (Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy) or the NEJM (New England Journal of Medicine) blog. They provide the "why" behind the news without the clickbait.

Moving Forward With Eyes Open

The story of human to human transmission of bird flu is still being written. We are currently in a "period of heightened surveillance." It’s like watching a storm on radar; we see the clouds gathering, we see the rotation, but it hasn't touched down as a tornado in the general population.

We have the tools to stop it: wastewater tracking, rapid sequencing, and a pre-existing vaccine strategy. The bottleneck is often political and social, not just biological. We need better protections for migrant farmworkers so they feel safe reporting illness without fear of deportation or job loss. That's where the next "Missouri-style" cluster will likely start—in the shadows of the agricultural industry.

If we want to prevent a pandemic, we have to look where the virus is actually playing. Right now, that’s on the farms. If we contain it there, the "human to human" headline stays a hypothetical for another day.

Actionable Insights for Your Health:

- Check the CDC Wastewater Map: Look at your local area for "Influenza A" spikes that occur outside of the normal winter flu season. This can be an early warning sign.

- Get Your Regular Flu Shot: It doesn't protect against H5N1, but it prevents you from getting both at once, which reduces the chance of the viruses "swapping" DNA in your body.

- Practice Basic Biosecurity: If you have backyard chickens, keep their food and water away from wild birds. Use dedicated shoes for the coop that don't go inside your house.

- Monitor Symptoms: If you’ve been near livestock and develop a fever or red, itchy eyes, tell your doctor specifically about the animal exposure. Standard flu tests might miss H5N1, and specialized testing is required.