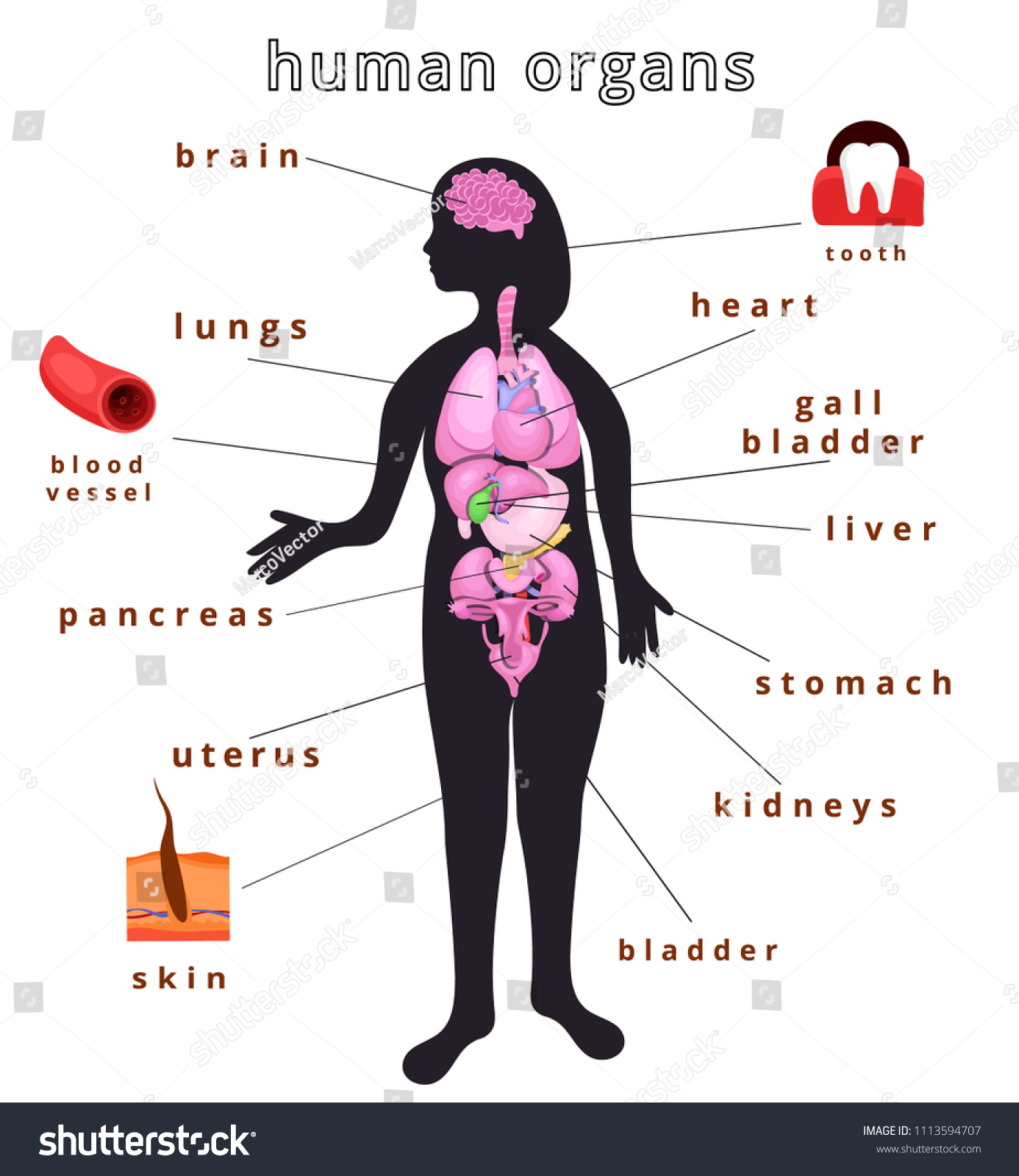

You’ve seen them in every doctor’s office since you were five. Those glossy, slightly intimidating posters showing a transparent person with perfectly color-coded insides. Red for arteries. Blue for veins. Neon green for the lymphatic system. It makes everything look so organized, right? Like the internal wiring of a high-end gaming PC.

But honestly? A real human organ anatomy diagram is a massive oversimplification.

If you actually opened someone up—which, please don't—you wouldn't find a rainbow. You’d find a lot of beige, some deep reds, and a whole lot of slippery connective tissue called fascia that holds everything together like biological Saran Wrap. Most diagrams leave out the "mess" because it’s hard to teach. They treat the body like a collection of separate parts, but your liver doesn't just sit there in a vacuum; it’s physically crowded by the stomach, the diaphragm, and the right kidney.

The Problem With the Static View

Standard diagrams usually show the "anatomical position." You know the one: standing straight, palms forward, looking ahead. It’s the gold standard for medical communication. But humans move.

When you sit down, your abdominal organs shift. When you take a deep breath, your diaphragm—that thin, dome-shaped muscle—flattens out and pushes your liver and stomach downward by a couple of centimeters. Static images make us think our organs are bolted to our ribs. They aren't. They’re floating, pulsing, and sliding against each other.

Take the heart. Most people think it’s on the left side of the chest. It’s actually more central than you’d think, tucked behind the sternum, just tilted slightly to the left. If you’re looking at a human organ anatomy diagram and the heart looks like a Valentine’s Day sticker, you’re looking at a bad diagram. Real hearts are lumpy, covered in yellow fat deposits (even in healthy people), and shaped more like a twisted cone.

What We Get Wrong About the Digestive Track

People talk about the "stomach" as if it’s their entire belly. It’s not. The stomach is actually tucked way up under your left ribs. Most of what people point to when they say "my stomach hurts" is actually the small intestine.

🔗 Read more: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

The small intestine is a logistical nightmare. It’s roughly 20 feet of tubing crammed into a space the size of a basketball. Most diagrams show it as a neat coil. In reality, it’s a chaotic tangle held in place by the mesentery. For a long time, we just thought the mesentery was "extra" tissue. Then, around 2016, researchers like J. Calvin Coffey at the University of Limerick argued it should be classified as a distinct organ itself.

This changed how we look at the human organ anatomy diagram entirely. It turns out the "background noise" in the body is often just as important as the big players like the heart or lungs.

The Liver: The Quiet Powerhouse

If there’s an MVP of the abdominal cavity, it’s the liver. It’s huge. It’s the largest solid organ in your body, weighing about three pounds. It’s also incredibly resilient. You can cut away a massive chunk of it, and it will grow back.

In most diagrams, it’s a big dark red wedge on the right side. But its relationship with the gallbladder is what usually trips people up. The gallbladder is this tiny, pear-shaped sac tucked under the liver. It stores bile. When you eat a greasy burger, it squirts that bile into the small intestine to break down the fat. If you see a diagram where the gallbladder is the size of a kidney, someone messed up the scale.

Your Lungs Aren't Equal

One of the coolest things about human anatomy that rarely makes it into basic sketches is the asymmetry of the lungs. Your right lung has three lobes. Your left lung only has two.

Why? Because the heart needs a place to stay.

💡 You might also like: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

The left lung has a little "indent" called the cardiac notch. It’s a literal carved-out space to accommodate the heart’s tilt. If you look at a human organ anatomy diagram and the lungs are perfectly symmetrical, it’s a stylized illustration, not a medical reality.

Why the Interstitium Changed Everything

Medical science is never "done." For centuries, we thought we had mapped every part of the human body. Then, in 2018, a study published in Scientific Reports identified the interstitium.

Think of it as a highway of fluid-filled spaces between tissues. It’s everywhere—under your skin, lining your gut, surrounding your blood vessels. Before this, we just thought it was solid connective tissue because when you slice a sample for a microscope, the fluid drains out and the structure collapses. It’s like looking at a dried-out sponge and forgetting it used to hold water.

This discovery means that every human organ anatomy diagram printed before the late 2010s is technically missing a massive, body-wide network that might be crucial for how cancer spreads or how we feel pain.

Variation Is the Only Constant

There is a thing called Situs Inversus. It’s a rare condition where a person’s organs are a literal mirror image of the "standard" diagram. The heart is on the right, the liver is on the left. It’s rare, affecting about 1 in 10,000 people, but it proves a vital point: the "average" body doesn't exist.

Even in "normal" people, the shape of the kidneys or the branching of the arteries varies wildly. Some people have an extra rib. Some are born with one kidney and never know it until they get an ultrasound for something else.

📖 Related: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

How to Actually Use an Anatomy Diagram

If you're a student or just a curious person trying to understand your body, don't just look at one image. Compare different versions.

Look at 3D renderings that allow you to rotate the torso. Static 2D images are great for memorizing names, but they fail to show the depth. The kidneys, for example, are "retroperitoneal." That’s a fancy way of saying they sit behind the rest of your organs, closer to your back than your belly button. A flat human organ anatomy diagram makes it look like they’re just hanging out next to the intestines. They’re actually tucked way back there, protected by your lower ribs and heavy back muscles.

Actionable Steps for Better Body Literacy

Don't just stare at a poster and assume you know where your bits are. If you want to understand your internal landscape, try these steps:

- Palpate your own landmarks. Find your "sternal notch"—the dip at the base of your throat. Use that to trace down to your sternum. Feel where your ribs end. This is the boundary of your thoracic cavity.

- Use the "Hand Rule" for the Liver. Place your right hand over the lower part of your right rib cage. Most of your liver is protected right under there.

- Trace your pulse. Don't just do the wrist. Find the carotid artery in your neck or the femoral artery in your groin. Visualizing the "pipes" helps the human organ anatomy diagram make sense in 3D.

- Check the source. If you're looking at a diagram online, check if it’s from a reputable source like the Mayo Clinic, Gray’s Anatomy (the book, not the show), or university medical departments. Avoid generic "stock photo" anatomy which often gets proportions hilariously wrong.

- Download a 3D app. Tools like Complete Anatomy or BioDigital Human let you peel away layers of muscle to see how organs actually stack. It’s way better than a flat piece of paper.

The human body is a crowded, pulsing, wet, and incredibly efficient machine. A diagram is just a map. And as any hiker will tell you, the map is not the territory. Knowing the difference is what makes you actually literate about your own health.

Instead of looking for a "perfect" image, look for one that acknowledges the complexity. Understand that your spleen is a tiny purple fist on the left, your pancreas is hidden behind your stomach, and your "insides" are far more dynamic than a textbook ever lets on.