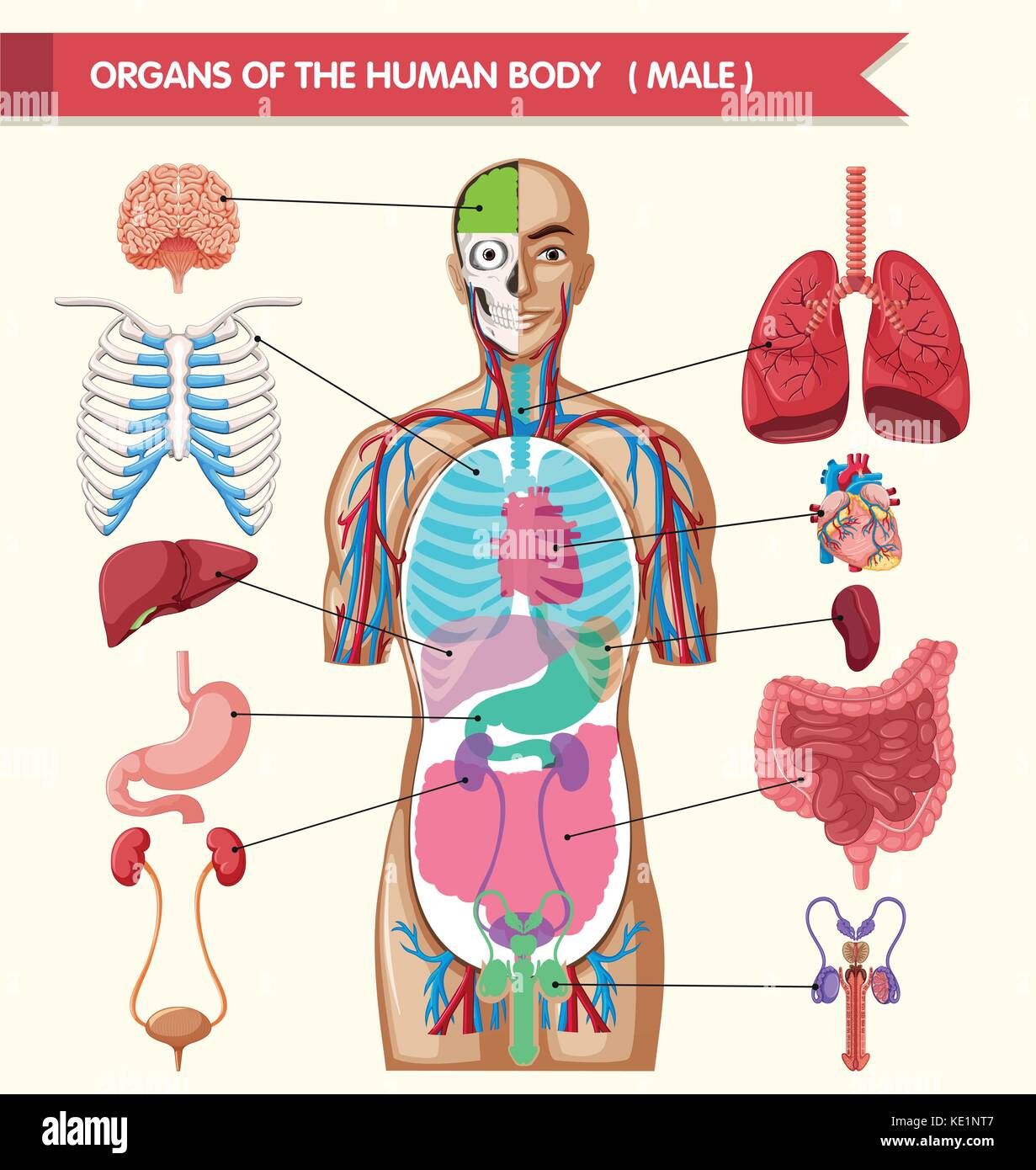

Ever looked at a medical poster in a doctor's office and felt like you were staring at a subway map of Tokyo? It's a mess of colors, lines, and overlapping shapes. Honestly, most people think they know where their liver is, but they're usually off by three inches. That matters. Understanding a human anatomy map organs layout isn't just for surgeons or med students; it’s about knowing why that weird twinge in your side might actually be your gallbladder and not just a pulled muscle.

Bodies are weird. They're crowded.

Think about it. Your torso is basically a high-stakes game of Tetris where nothing is allowed to touch but everything is packed tight. If you move one thing, something else has to shift. This isn't just a collection of parts; it's a living, breathing topographical map.

The Vertical Stack: Redefining the Human Anatomy Map Organs

Most of us imagine our organs sitting side-by-side like groceries in a bag. That’s wrong. The reality of a human anatomy map organs setup is much more "3D." It’s layered.

🔗 Read more: Why Videos of 10-Year-Old Girls Walking Are a Growing Trend in Youth Sports Biomechanics

Take the retroperitoneal space. This is the "back room" of your abdomen. Your kidneys don't just hang out in the middle of your belly; they are tucked way back against the muscles of your spine. This is why kidney pain feels like a backache. If you're looking at a standard map of the body, you see the intestines first. You have to peel back layers of fascia, the greater omentum (which is basically a fatty apron), and several feet of tubing just to see the heavy hitters.

The diaphragm is the real MVP here. It’s a thin, dome-shaped muscle that acts as the border patrol between your chest and your abdomen. Everything above it—heart, lungs—is protected by the rib cage. Everything below it—stomach, liver, spleen—is part of the digestive and filtration powerhouse. When you breathe, this entire map shifts. Your liver actually moves down an inch or two every time you inhale. It's a dynamic map, not a static one.

The Liver and Gallbladder: The Heavy Neighbors

The liver is massive. It’s the largest internal organ, weighing in at about three pounds, and it sits almost entirely on your right side. If you put your hand over your lower right ribs, you're basically touching it.

But here’s the kicker: it’s not just a filter. It’s a chemical plant.

- It produces bile.

- It stores glucose.

- It breaks down toxins.

- It regulates blood clotting.

Right tucked underneath that giant liver is the gallbladder. It’s tiny, pear-shaped, and easy to miss on a low-resolution human anatomy map organs diagram. Its only job is to store the bile the liver makes. When you eat a greasy burger, the gallbladder squeezes that bile into the small intestine. This is where people get confused. They feel pain in their upper right quadrant and think "stomach ache," but the stomach is actually further to the left.

Dr. Henry Gray, whose work in Gray's Anatomy remains the gold standard, famously detailed these relationships with painstaking precision. He noted how the liver’s "bare area" is the only part not covered by the peritoneum, allowing it to attach directly to the diaphragm. This level of physical connection is why your breathing can affect your digestion and vice-versa.

The Gut Logic: Ten Meters of Complexity

If you unspooled your small intestine, it would be about 20 feet long. That’s huge. How does it fit? It folds. These folds, known as plicae circulares, aren't just for space-saving; they maximize surface area for nutrient absorption.

The large intestine, or colon, acts like a frame for the small intestine. It starts in the bottom right (the cecum, where the appendix hangs out), goes up the right side (ascending), crosses the middle (transverse), and goes down the left (descending).

Most people don't realize how high the transverse colon sits. It’s right under your ribs. When you feel "bloated" or have "gas pain" high up in your chest, it’s often just the "splenic flexure"—the corner where the colon turns downward near the spleen. It’s a common mistake to think this is heart-related because of the proximity.

👉 See also: What Percentage of Humans Are Left Handed: The Reality Most People Get Wrong

The Left-Side Secrets: Spleen and Pancreas

On the left side of your human anatomy map organs layout, things get crowded. The stomach is a J-shaped sac that sits mostly on the left, tucked under the liver's left lobe. Behind the stomach lies the pancreas.

The pancreas is a "ghost" organ in many ways. You can't feel it from the outside. It’s long and flat, crossing the midline of the body. It’s both an endocrine gland (making insulin) and an exocrine gland (making digestive enzymes). Because it’s so deep in the body, problems with the pancreas often manifest as pain that "bores" straight through to the back.

Then there’s the spleen. It’s about the size of a fist. It’s your blood's primary security system, filtering out old red blood cells and holding a reserve of white blood cells. It’s tucked so far back under the left ribs that if it’s healthy, a doctor can’t even feel it. If they can feel it, it’s usually because it’s swollen from infection or injury.

Thoracic Real Estate: Heart and Lungs

Moving up past the diaphragm, the map changes. It’s all about protection. The lungs aren't just two balloons; they are spongy, asymmetric structures. The right lung has three lobes, while the left lung only has two.

Why? Because the heart needs a place to sit.

The heart is tilted. Its "apex" or bottom point aims toward your left hip. This "cardiac notch" in the left lung is a perfect example of how the human anatomy map organs design prioritizes space. The mediastinum is the central compartment of the chest that holds the heart, the esophagus, and the trachea. It’s the highway system for your body’s air and fuel.

The Pelvic Floor: The Foundation

We often stop the map at the waist, but the pelvic organs are the foundation. This is where the bladder and reproductive organs live. The bladder is like a balloon; when it’s empty, it hides behind the pubic bone. When it’s full, it expands upward into the abdominal cavity.

This is a key point for clinical diagnosis. A "pelvic" pain might actually be an abdominal issue if an organ is displaced or enlarged. In women, the uterus sits right between the bladder and the rectum. This proximity is why pregnancy often leads to frequent urination—the physical map is literally being rewritten by the growing fetus.

Why This Mapping Actually Matters for You

Understanding your internal geography isn't just a fun fact for trivia night. It's about self-advocacy. When you go to a doctor and say "it hurts here," being able to distinguish between your "stomach" (the organ) and your "abdomen" (the area) changes the diagnostic path.

If you feel sharp pain in the lower right, you're looking at the appendix or the ascending colon. If it's the upper left, it's likely the stomach or spleen.

We often ignore the "interstitium," a recently "discovered" organ that is essentially a network of fluid-filled spaces throughout the body's connective tissues. This reminds us that the human anatomy map organs we see in books are simplified. We are still finding new ways to define what an organ even is.

Moving Toward Better Body Literacy

You don't need a medical degree to be literate in your own biology. Start by visualizing the "big three" areas:

- The Right Upper Quadrant: Liver and gallbladder.

- The Left Upper Quadrant: Stomach, spleen, and the tail of the pancreas.

- The Lower Right Quadrant: The appendix and the start of the large intestine.

Next time you feel a sensation in your torso, don't just call it a "belly ache." Try to map it. Is it deep or superficial? Does it move when you breathe?

📖 Related: Woman Top Sex Position: Why It’s Actually The Most Practical Way To Reach Orgasms

To take this further, spend five minutes looking at an interactive 3D anatomy model—there are plenty of reputable ones from university medical centers like the University of Michigan or the Mayo Clinic. Physical awareness reduces anxiety. When you know where your organs are supposed to be, you become a much better judge of when something is actually wrong.

Pay attention to your posture as well. Slouching physically compresses these organs, particularly the stomach and lungs, which can lead to acid reflux or shallow breathing. Sitting up straight isn't just about looking good; it's about giving your internal map the space it needs to function. Consider incorporating diaphragmatic breathing exercises once a day to ensure your "border patrol" muscle is moving through its full range of motion, which helps massage the abdominal organs and promotes better circulation through the entire map.