You’ve probably stared at those glossy posters in a waiting room. You know the ones—the neon-red heart, the blue-tinted veins, and the lungs that look like perfectly symmetrical sponges. Honestly, most human anatomy images organs lovers see are pretty misleading. They're cleaned up. They're color-coded for a textbook, not for real life. If you actually saw a human liver during surgery, it’s not that bright "liver-colored" shade you see in diagrams; it’s a deep, dark, heavy maroon that looks almost like wet clay.

Understanding how our insides actually fit together is kind of a trip. We tend to think of organs as these separate "parts" in a machine, like a spark plug or a fan belt. But that’s not how it works at all. Your organs are basically a singular, continuous web of tissue wrapped in something called fascia. If you pull on one part, the rest feels it.

The Problem With Standard Human Anatomy Images Organs Diagrams

Most digital renderings simplify things so much they lose the "human" element. Look at the mesentery. For decades, it was just thought of as some random bits of connective tissue holding the guts in place. It wasn't until around 2016 that researchers like J. Calvin Coffey at the University of Limerick officially reclassified it as a single, continuous organ.

If you look at older human anatomy images organs collections, the mesentery is barely there. It looks like scraps. This matters because how we see the body dictates how we treat the body. When we view the digestive system as a series of disconnected tubes, we miss the "highway" system that links them all together.

Real anatomy is messy. It’s crowded.

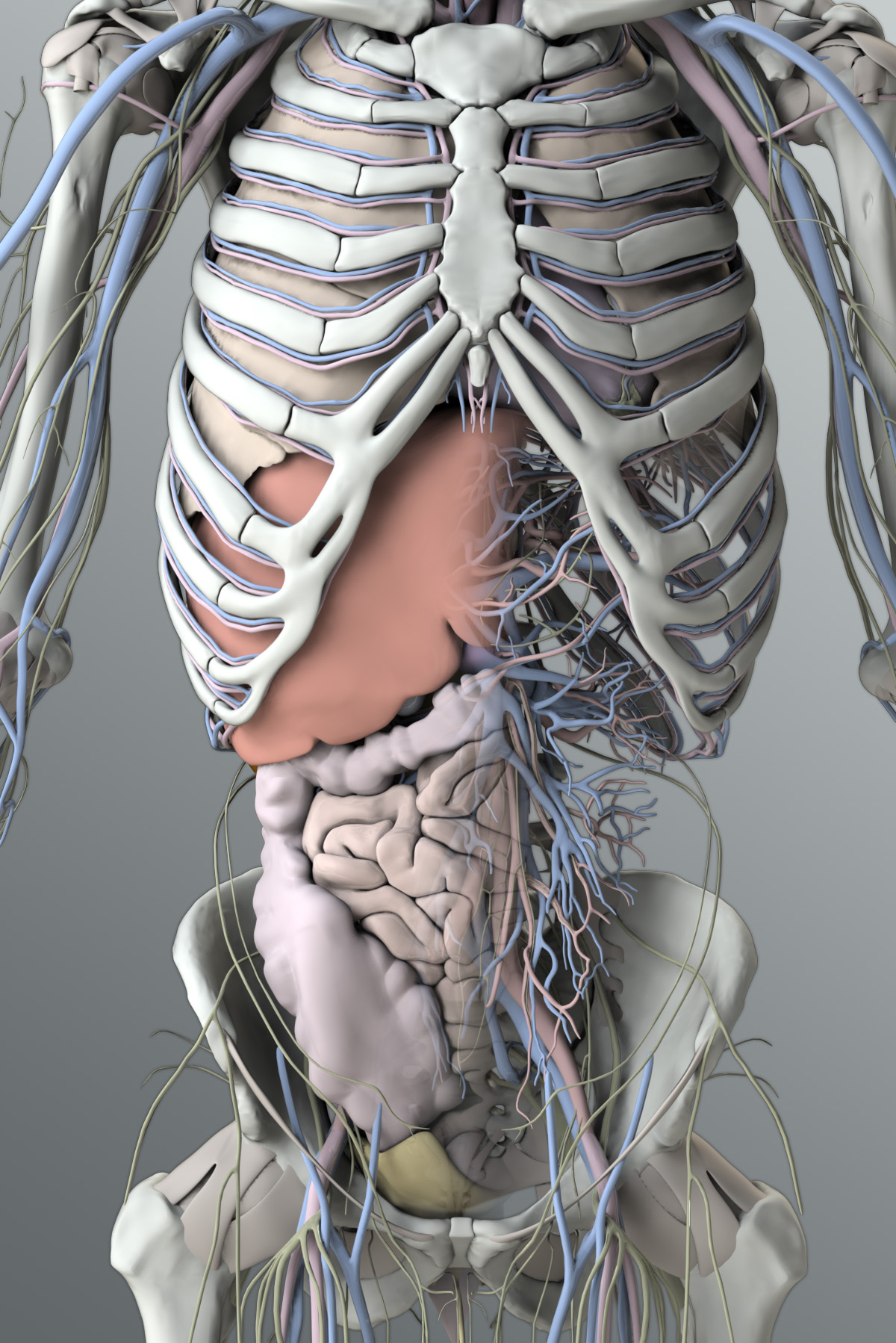

Ever wonder why a "stomach ache" can feel like it's in your chest or your lower back? It's because your organs are packed in there with zero wasted space. There isn't "air" between your liver and your diaphragm. They are literally sliding against each other. This is why high-quality, 3D cross-section images are so much more valuable than the flat drawings we grew up with. They show the pressure. They show the intimate contact.

Why Your Liver is the Actual MVP (and Looks Nothing Like the Pictures)

Everyone talks about the heart. Sure, it’s a pump. Important? Obviously. But the liver is a chemical processing plant that performs over 500 functions simultaneously. In many human anatomy images organs displays, the liver is just a big wedge on the right side.

👉 See also: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

In reality, it's massive. It’s the largest internal organ and it’s incredibly resilient. You can cut away 70% of it, and it can grow back to full size in months. That’s some sci-fi level regeneration.

When you look at specialized imaging—like a CT scan or a high-resolution MRI—you start to see the vascularity. It’s a dense forest of blood vessels. This is why blunt force trauma to the abdomen is so dangerous. It’s not just about "bruising" an organ; it's about the fact that the liver is basically a giant sponge filled with blood. If it tears, it’s a surgical emergency of the highest order.

The Heart Isn't Where You Think It Is

Go ahead, put your hand over your heart. You probably put it on the far left of your chest, right?

Wrong.

Your heart is actually situated pretty much in the dead center of your chest, tucked behind the sternum. The "left-sided" myth comes from the fact that the bottom of the heart, the apex, points toward the left. That’s where the beat is strongest, so that's where you feel it.

If you look at human anatomy images organs that show the ribcage removed, you'll see the heart is cradled by the lungs. The left lung is actually smaller than the right lung specifically to make room for that tilt of the heart. Nature is surprisingly pragmatic about floor space.

✨ Don't miss: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

The "Second Brain" Tucked in Your Gut

We need to talk about the Enteric Nervous System (ENS).

If you look at a standard anatomical drawing of the intestines, it looks like a bunch of pink sausages. What those images usually fail to show is the massive web of 100 million nerve cells lining your gastrointestinal tract.

This isn't just for digestion. This "brain" in your gut communicates directly with the brain in your head via the Vagus nerve.

This is why you get "butterflies" when you're nervous. It's not a metaphor. It's your brain sending a literal "code red" to the neurons in your gut. Modern human anatomy images organs are starting to include "nervous system overlays" that show this connection, and honestly, it’s way more complex than the brain itself in some ways. It operates independently. Even if the Vagus nerve were cut, the gut could still manage digestion on its own. It's the only part of the body with that kind of autonomy.

Seeing the Invisible: The Lymphatic System

Most people can point to their lungs. Most can find their kidneys (which, by the way, are much higher up than you think—they’re tucked under your lower ribs, not down by your belt).

But almost nobody can visualize the lymphatic system.

🔗 Read more: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

In a lot of human anatomy images organs galleries, the lymph system is shown as a few green dots near the armpits or groin. In a real body, it's everywhere. It’s a secondary circulatory system that carries "lymph"—a clear fluid containing white blood cells.

It doesn't have a pump.

Unlike the heart, which forces blood through your veins, the lymph system relies on you moving. When you walk, your muscles squeeze the lymph vessels and push the fluid along. This is why sitting all day makes you feel sluggish and "puffy." Your internal drainage system is literally backed up because you aren't providing the mechanical squeeze it needs to function.

How to Use Anatomy Images to Actually Improve Your Health

Don't just look at these images for a biology test. Use them to visualize what's happening when things feel "off."

If you have lower back pain, stop looking at bone charts and start looking at images of the Psoas muscle and the kidneys. The kidneys sit right against the back muscles. Sometimes "back pain" is actually just your kidneys crying for more water.

When you look at human anatomy images organs of the lungs, notice the diaphragm—that big dome-shaped muscle underneath them. Most people breathe "shallow" into their upper chest. But if you look at the anatomy, you see the lungs expand downward. To breathe efficiently, you have to move that diaphragm. Visualizing that muscle dropping down can actually lower your heart rate in seconds.

Real-World Action Steps for Better "Internal Awareness"

- Check Your Posture Against Your Organs: Slumping doesn't just hurt your spine; it compresses your digestive organs. Look at a side-profile anatomy image. When you slouch, you’re basically putting your stomach and liver in a hydraulic press. Stand up to give them "breathing room."

- Visualize the Vagus Nerve: When you’re stressed, look at a map of the Vagus nerve. It touches the heart, lungs, and gut. Slow, deep "belly breaths" physically stimulate this nerve, signaling your entire organ system to chill out.

- Hydrate for Volume: Your blood volume directly affects organ perfusion. If you're dehydrated, your blood gets "thicker," and your kidneys have to work twice as hard to filter it. Look at the tiny capillaries in a kidney diagram—they’re thinner than a human hair. Don't clog them with sludge.

- Move for Lymphatic Drainage: Since the lymph system has no pump, you are the pump. Every 30 minutes of sitting should be met with 2 minutes of walking or jumping jacks to "flush" the system.

The human body isn't a collection of parts. It’s a high-pressure, fluid-filled, interconnected miracle. The next time you see human anatomy images organs on a screen, remember that everything is touching, everything is talking, and everything is moving. You aren't just "holding" your organs; you are your organs. Treat them like the high-performance tech they are.