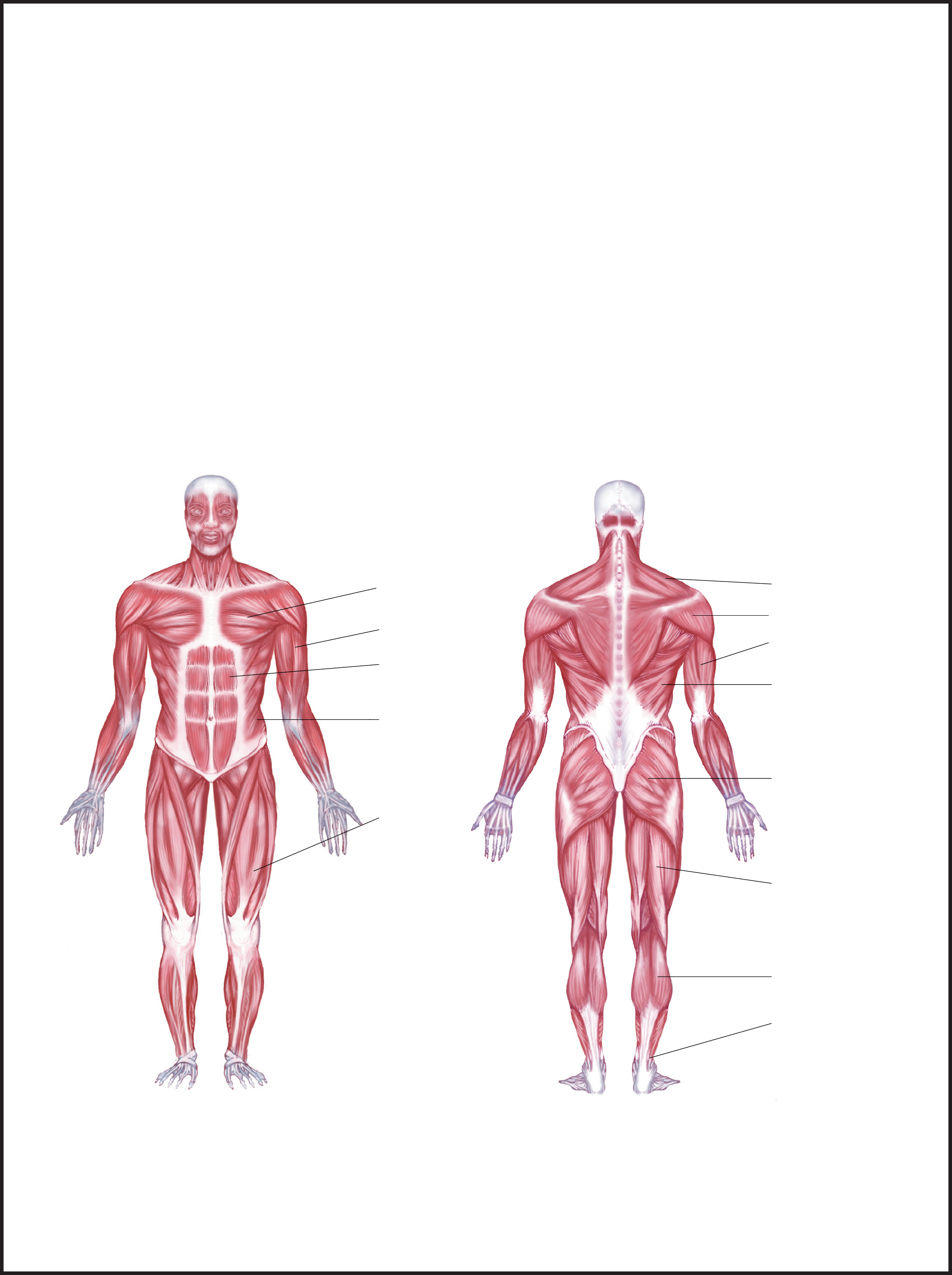

You’ve seen them a thousand times. Every doctor’s office, high school biology classroom, and dusty corner of a local CrossFit box has one hanging on the wall. It’s that skinless, red-and-white, hyper-vascularized human anatomy diagram of muscles that looks like it belongs in a horror movie. We look at it and think, "Okay, that’s me." But honestly? It’s a massive oversimplification.

The body isn't a collection of neatly labeled stickers.

It’s a chaotic, overlapping, messy web of tissue that doesn't always look like the textbook says it should. If you’ve ever tried to pinpoint why your shoulder hurts by staring at one of these charts, you know the frustration. You see the deltoid. You see the pectoralis major. But you don't see the reality of how they actually interact in a living, breathing person.

The Problem with the Standard Human Anatomy Diagram of Muscles

Most diagrams are based on "idealized" cadavers. These are often older bodies or specific specimens that have been preserved in ways that make the muscles look more distinct than they actually are in a 25-year-old athlete or a 50-year-old desk worker.

Muscles don't just start and stop. They blend.

Take the serratus anterior—those "boxer's muscles" on the ribs. On a human anatomy diagram of muscles, they look like clean, finger-like projections. In reality, they are deeply integrated with the external obliques. You can't really train one without moving the other. The diagram treats them like separate departments in a corporate office, but in your body, they’re more like a startup where everyone is doing three different jobs at once.

We also have to talk about fascia. Standard diagrams usually strip away the fascia—the silvery, cling-wrap-like connective tissue—to show the "pretty" red muscle underneath. This is a mistake. Without fascia, your muscles are just piles of meat. Fascia is what actually transmits force. If you’re looking at a muscle map to understand movement, and that map ignores the fascial lines, you're basically looking at a map of a city that doesn't show any of the streets.

It’s Not Just One Layer

Most people think of their muscles as a single layer under the skin. Wrong.

Think of your back. You have the trapezius and the latissimus dorsi on the surface. These are the "show" muscles. But underneath them? You’ve got the rhomboids, the levator scapulae, and the serratus posterior. And deeper still, you have the erector spinae group. A basic human anatomy diagram of muscles often struggles to show this depth without becoming a confusing mess of colors.

✨ Don't miss: Fruits that are good to lose weight: What you’re actually missing

When you feel a "knot" in your back, it’s rarely just in the top layer. It's usually a communication breakdown between these layers. They're supposed to slide past each other like silk. When they get "glued" together due to dehydration or lack of movement, that’s when the pain starts.

The Big Muscle Groups You’re Misunderstanding

Let's look at the glutes. Everyone talks about the gluteus maximus because it’s the biggest muscle in the body and, frankly, it’s what fills out your jeans.

But if you look at a more sophisticated human anatomy diagram of muscles, you’ll see the gluteus medius and minimus hiding underneath. These are the real MVPs of walking. If your "med" is weak, your knee is going to cave in when you run. You’ll blame your knee. You’ll buy expensive braces. But the problem is actually a tiny muscle in your butt that the diagram didn't emphasize enough for you to care about.

Then there’s the core.

Everyone wants a six-pack. That’s the rectus abdominis. But the rectus abdominis is basically just a fancy postural muscle. The real work is done by the transverse abdominis (TVA). This is your body’s internal weight belt. It wraps around your midsection horizontally. Most diagrams show it as a flat sheet, but it’s more like a living corset. If you only train what you see in the mirror, you’re missing the foundational strength that keeps your spine from collapsing.

Why Variation is the Only Constant

Dr. Gil Hedley, a famous "somanaut" who performs integral anatomy dissections, has spent years showing that no two bodies look the same inside.

One person might have a bicep with two heads (hence the name "bi-cep"). Another might have three. Some people are literally missing muscles that appear on every human anatomy diagram of muscles ever printed, like the palmaris longus in the forearm. About 14% of the population doesn't even have it.

If you're staring at a diagram trying to find a muscle that you literally don't possess, you're going to have a bad time. This anatomical variation is why one person can squat "ass-to-grass" with no effort, while another person’s hip sockets are built in a way that makes deep squatting physically impossible without bone hitting bone. The diagram shows the "average," but nobody is average.

🔗 Read more: Resistance Bands Workout: Why Your Gym Memberships Are Feeling Extra Expensive Lately

How to Actually Use a Muscle Diagram Without Getting Fooled

Don't treat it like a static map. Treat it like a general suggestion.

When you look at a human anatomy diagram of muscles, don't just look at where the muscle is. Look at where it attaches. These are the "origins" and "insertions." If a muscle attaches to your humerus (upper arm) and your scapula (shoulder blade), you know that muscle's job is to move those two bones closer together.

The Kinetic Chain Reality

Nothing happens in isolation. If you pull a muscle in your calf (the gastrocnemius), your body is going to change the way you walk. This shifts the load to your hamstring, which then pulls on your pelvis, which then tilts your lower back.

A static human anatomy diagram of muscles can't show this "kinetic chain." It makes it look like the calf is its own island. It isn't. It’s the first link in a long, interconnected whip.

- The Posterior Chain: This is the group of muscles running from your heels to your skull. It includes the calves, hamstrings, glutes, and spinal erectors. In modern life, because we sit so much, this chain is usually "turned off" and overstretched.

- The Anterior Chain: Your quads, hip flexors, and abs. These are usually tight and "short" from sitting.

- The Lateral Line: The muscles on the side of your body that stop you from toppling over.

Misconceptions That Just Won't Die

"Lactic acid causes muscle soreness."

Nope. Old news. Lactic acid (or lactate) is actually a fuel source and is usually cleared from your system within an hour of working out. That burning sensation two days later? That’s DOMS (Delayed Onset Muscle Soreness), which is caused by microscopic tears in the muscle fibers and the subsequent inflammatory response.

Another one? "You can spot-reduce fat by working a specific muscle."

Looking at a human anatomy diagram of muscles and deciding to do a thousand crunches to "burn belly fat" is a waste of time. You’re strengthening the muscle underneath the fat, but the fat on top is metabolized globally. Your DNA decides where the fat comes off first, not your workout routine.

💡 You might also like: Core Fitness Adjustable Dumbbell Weight Set: Why These Specific Weights Are Still Topping the Charts

Real-World Application: Improving Your Mind-Muscle Connection

So, how do you use this info?

Next time you’re at the gym or even just stretching at home, pull up a high-quality, 3D human anatomy diagram of muscles. Look at the muscle you’re trying to target. Close your eyes and try to visualize it contracting.

This isn't "woo-woo" science. Research in the European Journal of Applied Physiology has shown that focusing on the specific muscle being worked—the mind-muscle connection—can actually increase muscle fiber recruitment.

If you're doing a row and you just pull the weight, your biceps do most of the work. But if you look at the diagram, see the latissimus dorsi, and visualize those fibers pulling your elbow back, you’ll actually engage your back more effectively.

Actionable Steps for Better Movement

- Stop looking at 2D charts. Use apps like Complete Anatomy or Visible Body. These let you rotate the body and peel back layers, which is way more accurate to how you actually function.

- Focus on the "Attaching" bones. Don't just learn muscle names. Learn what bones they pull on. It makes every exercise make way more sense.

- Hydrate your fascia. Fascia needs water to stay slippery. If you're dehydrated, your "muscle map" becomes a stiff, tangled mess, no matter how much you stretch.

- Acknowledge your uniqueness. If a certain movement feels "wrong" in your joints despite what the "perfect form" videos say, trust your anatomy. Your bone structure might not match the diagram.

The human anatomy diagram of muscles is a starting point, a legend for a map that is constantly changing. Use it to learn the language of your body, but don't let it tell you how you're supposed to feel. Your body is a three-dimensional, fluid system that no 2D poster can ever fully capture.

Start by identifying one area where you feel chronic tension. Find it on a 3D model. Look at what’s underneath it. Often, the spot that hurts isn't the problem—it's just the part of the chain that's screaming the loudest because another muscle isn't doing its job.

Check your posture right now. Are your shoulders rolled forward? Look at the diagram of the pectoralis minor. It’s likely tight and pulling your scapula forward. Stretch the pec, and the back pain might just vanish. That's the power of actually understanding the map.