You're standing in front of a bike, a lathe, or maybe a custom-built RC car, staring at two interlocking sets of teeth. One is spinning fast; the other is barely moving. You know there’s a mathematical relationship there, but your brain keeps trying to overcomplicate it. Honestly, learning how to work out gear ratio isn't about memorizing a scary calculus formula. It’s basically just counting.

If you have a gear with 10 teeth driving a gear with 40 teeth, that big one is going to turn once for every four times you spin the little one. That's it. That is the soul of the mechanical advantage. We use these ratios to trade speed for torque, or vice versa, and getting it wrong means your motor burns out or your car feels like it's driving through molasses.

The Core Math (It’s Simpler Than You Think)

Let's get the "scary" part out of the way first. The fundamental equation for a simple gear pair is the number of teeth on the driven gear divided by the number of teeth on the driving gear.

💡 You might also like: TM List Gen 3: Why This Data Standard Still Breaks Everything (and How to Fix It)

The "driver" is the gear attached to the power source, like a motor or your bike pedals. The "driven" gear is the one receiving that power. If you’re a visual learner, just remember: Driven / Driver.

$$Gear Ratio = \frac{T_{driven}}{T_{driver}}$$

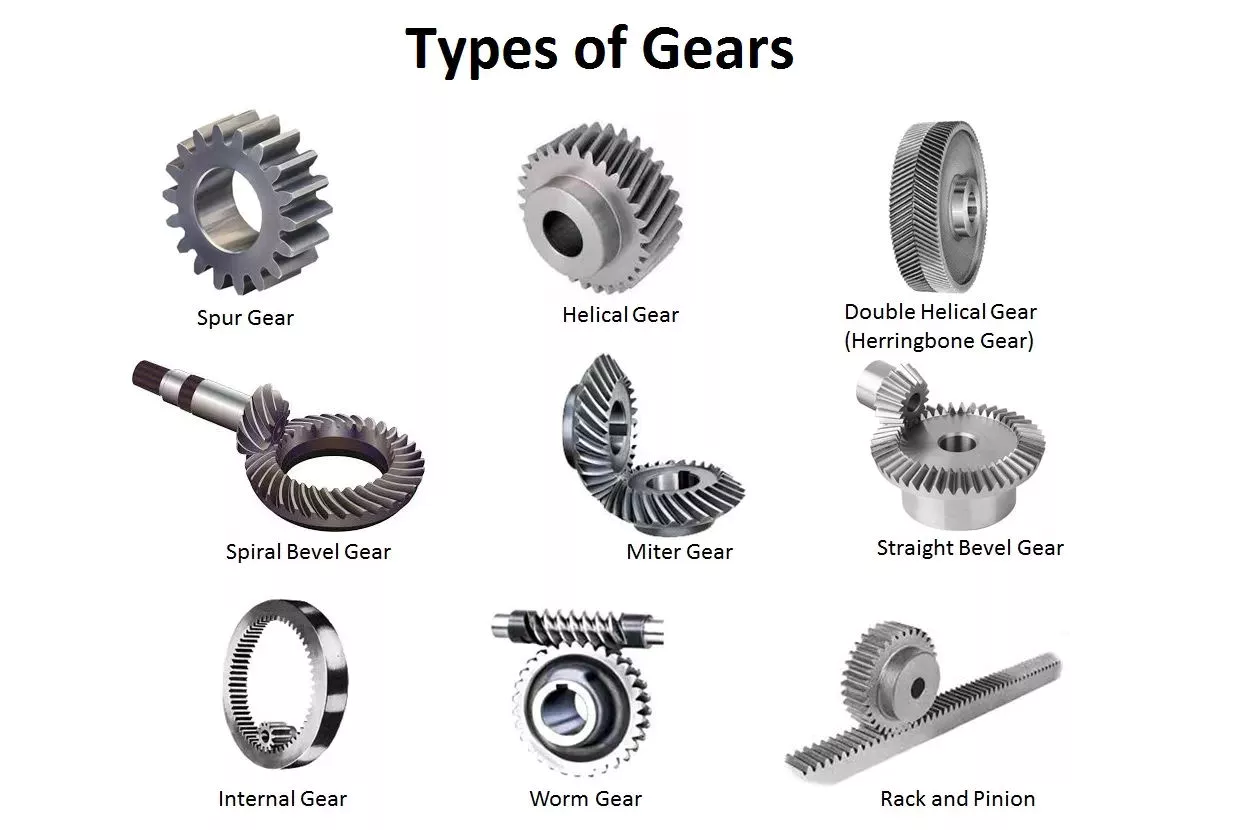

Say you've got a 20-tooth pinion (the small gear) on a motor and it’s turning a 60-tooth spur gear on an axle. You divide 60 by 20. The result is 3. We write that as 3:1. This means the motor has to spin three full times to make the axle spin once. You've lost speed, but you've tripled your torque. That’s why your car starts in first gear; you need that massive mechanical advantage to get two tons of metal moving from a dead stop.

Why How to Work Out Gear Ratio Actually Matters in the Real World

Most people think about gears only when something breaks. But if you’re into 3D printing, robotics, or even just trying to fix a vintage clock, you've gotta understand the "why" behind the numbers. A 1:1 ratio is boring—it just transfers motion. But once you move away from 1:1, you’re playing with the physics of work.

High gear ratios (like 10:1) are for climbing hills or lifting heavy loads. Low gear ratios (like 0.8:1, often called "overdrive") are for cruising at high speeds while keeping your engine RPMs low. If you've ever felt your legs spinning wildly on a downhill bike ride without actually going any faster, you’ve run out of gear ratio. You’re "spun out."

Don’t Get Tripped Up by Idler Gears

Here is a weird quirk that messes with everyone the first time they see it. Imagine three gears in a row. Gear A (driver) has 10 teeth. Gear B (the middle guy) has 50 teeth. Gear C (the final driven gear) has 20 teeth.

Most people start doing math for A to B, then B to C. They think the 50-tooth gear in the middle changes the ratio.

It doesn't.

The middle gear is called an idler gear. Its only jobs are to bridge a physical gap and to change the direction of rotation. If Gear A is 10 teeth and Gear C is 20 teeth, your ratio is 2:1. Period. The idler gear mathematically cancels itself out. You could put a gear with 1,000 teeth in the middle and the ratio between the first and last gear would remain exactly the same.

Dealing with Compound Gear Ratios

Now, things get a bit more "Expert Level" when you have multiple gears on the same shaft. This is a compound gear train. You see this in heavy machinery or the transmission of your car.

In a compound setup, you have pairs. You work out the ratio for each pair individually, then you multiply them together. You don’t add them. Never add them.

- Pair 1: 10-tooth driver to a 30-tooth driven = 3:1 ratio.

- Pair 2: A 10-tooth gear on that same second shaft driving a 40-tooth gear = 4:1 ratio.

- Total Ratio: $3 \times 4 = 12$. So, 12:1.

The input motor has to spin 12 times for the final output to spin once. This is how winches can pull thousands of pounds using relatively small electric motors. It’s all about stacking those ratios to create massive force.

💡 You might also like: Why 4k wallpaper for pc looks terrible on some monitors (and how to fix it)

The Misconception of "Perfect" Ratios

In the automotive world, especially with differentials, engineers often avoid "perfect" whole number ratios like 4:1. They prefer something like 4.11:1 or 3.73:1.

Why? It’s about wear and tear.

If you have a 10-tooth gear hitting a 40-tooth gear, the same teeth hit each other every single revolution. If there’s a tiny imperfection or a chip on one tooth, it will hammer the same spot on the other gear over and over. This creates a "rhythmic" wear pattern that leads to early failure. By using "hunting tooth" ratios (ratios that don't divide evenly), the teeth meet at different points each time, spreading the wear evenly across the entire gear set. It’s a subtle bit of engineering that makes your car last 200,000 miles instead of 20,000.

Real-World Tools and Measurement

Sometimes you can't count the teeth. Maybe the gear is partially obscured, or it’s too small to see clearly. In those cases, you work with circumference or diameter.

Since the teeth have to be the same size to mesh together, the ratio of the diameters is the same as the ratio of the teeth. If you measure a 2-inch drive pulley and a 6-inch driven pulley, you have a 3:1 ratio.

- Pro Tip: If you're working on a bike and want to know your "gear inches" (a common metric for cyclists), you take the ratio of the front chainring to the rear sprocket and multiply it by the diameter of the wheel. It tells you how far the bike travels with one pedal stroke.

Putting It Into Practice

If you're currently trying to figure out a project, stop guessing. Grab a marker. Put a dot on one tooth of the driver gear and a dot on the driven gear. Rotate the driver and count how many times it goes around until the driven gear makes one full circle.

💡 You might also like: That This User Is Under Surveillance Discord Meme: Why Your Profile Isn't Actually Flagged

If you're designing something from scratch, start with your "target." Do you need speed or power?

- Identify your motor's RPM and the torque it produces.

- Determine your required output (e.g., "I need this wheel to spin at 60 RPM to move the robot at the right speed").

- Divide the Input by the Output to find your required ratio.

- Select gears that fit your physical space while satisfying that math.

Understanding how to work out gear ratio is basically gaining a superpower over physics. It allows you to take a weak, fast motor and turn it into a slow, unstoppable force. Or, it lets you take a slow, powerful engine and turn it into a high-speed cruiser.

Next time you look at a mechanical device, don't just see a mess of metal. Look for the driver and the driven. Count the teeth. Do the division. Once you see the ratios, you see how the machine actually "thinks."

To get started on your own calculation, find the tooth count stamped on the side of most industrial gears or simply use a set of calipers to measure the pitch diameter. From there, the math is just a simple division away.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Count the teeth on your primary drive gear and your final driven gear.

- Divide the driven count by the driver count to establish your current baseline ratio.

- Check for idler gears and ignore their tooth counts for the final ratio calculation, using them only to determine the direction of rotation.

- Calculate your "hunting tooth" frequency if you are designing a high-load system to ensure long-term durability.