Most people think Tic Tac Toe is just a silly game for kids to pass the time on the back of a cereal box. It isn’t. Well, it is, but it’s also a solved game. In the world of game theory, "solved" means that if both players play perfectly, the outcome is predetermined. In this case, that outcome is always a draw. But here is the thing: most people don't play perfectly. They get distracted, they make "intuitive" moves that are actually mathematical disasters, and they fall into traps that have been documented for decades.

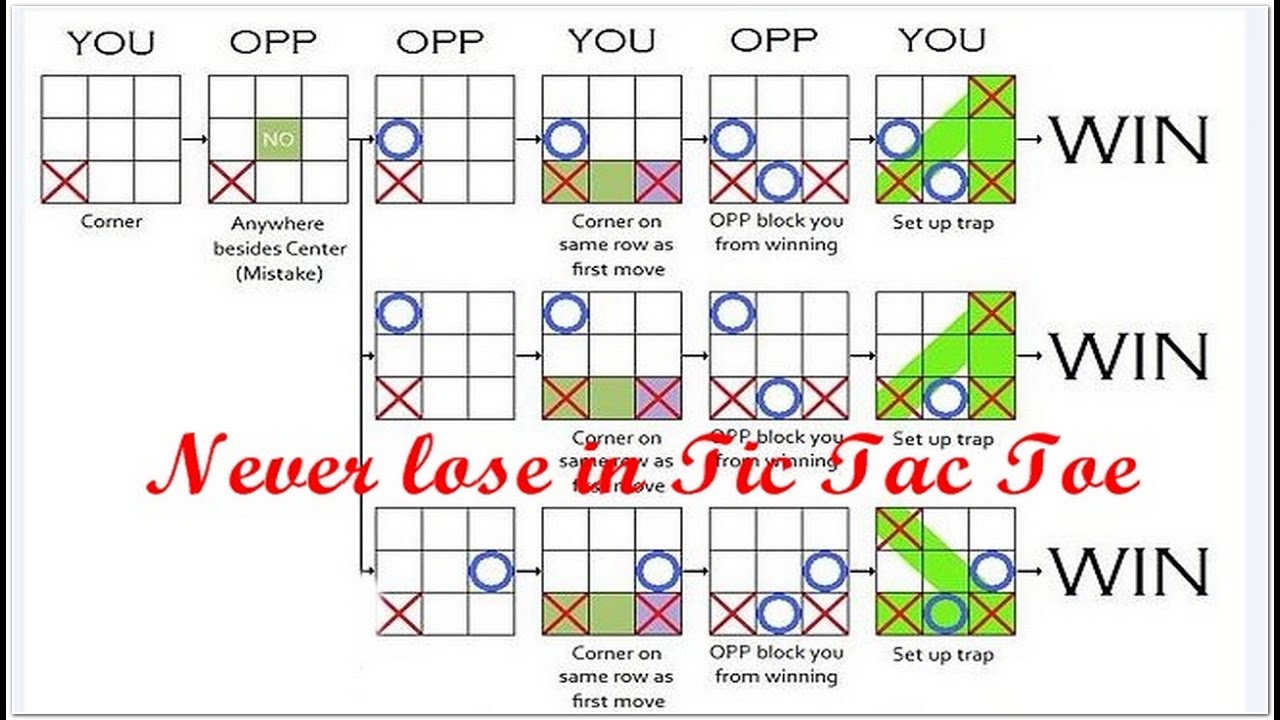

If you want to know how to win tic tac toe every time, or at least ensure you never, ever lose, you have to stop playing with your gut. You need to play like an algorithm. It’s about forcing your opponent into a "fork"—a scenario where they have two threats to block but only one move to make.

The first move is everything

Strategy starts before the first X or O even hits the paper. If you go first, you have a massive advantage. You aren't just playing; you're setting a trap. Most amateurs start in the center because it feels powerful. It’s not. While the center is good, the corners are statistically superior for creating traps.

Let’s say you take the top-left corner. Your opponent has eight possible squares to choose from. If they don't pick the center immediately, they have basically already lost. It sounds harsh, but it's true. If they pick any other edge or corner, you can force a win in about three moves. This is because corners contribute to three possible winning lines, whereas edges only contribute to two. By taking a corner, you maximize your "branching factor," a term used in combinatorial game theory to describe the number of possible moves that lead to a favorable state.

What happens when you go second?

Going second is about survival. You aren't playing to win; you’re playing to not lose, hoping your opponent gets cocky. If they start in a corner, you must take the center. If you don't take the center, you’re toast. If they start in the center, you must take a corner. Anything else gives them the leverage to set up a double-threat that you can’t escape.

The "Fork" is how to win tic tac toe every time

The "fork" is the holy grail of Tic Tac Toe. This happens when you create two ways to win at the same time. Since your opponent can only block one square per turn, the other one stays open, and you win on your next move.

💡 You might also like: Why the Disney Infinity Star Wars Starter Pack Still Matters for Collectors in 2026

Imagine this scenario. You take the top-left corner. They take the center (the smart move). You then take the bottom-right corner, creating a diagonal line. Now, they have to take an edge to block you. If they mess up and take another corner, you’ve got them. You place your third mark in a way that completes a second potential line.

Honestly, it’s kinda mean once you get the hang of it. You’re basically watching them realize they’ve lost two turns before the game actually ends. This is often referred to as a "double threat." In the 1950s, researchers like Donald Michie even built mechanical computers out of matchboxes—called MENACE (Matchbox Educable Naughts and Crosses Engine)—just to prove that a machine could learn these exact patterns through trial and error.

Common mistakes that lead to losing

People get lazy. They see two Xs in a row and their brain screams "BLOCK!" but they forget to look at the rest of the board. One of the biggest mistakes is failing to recognize the "Edge Trap."

If you are going second and your opponent takes two opposite corners (like top-left and bottom-right), and you have the center, do not take a corner for your next move. If you do, you’ve just handed them a win. You have to take an edge. Taking an edge forces them to block you, which breaks their ability to set up a fork. It’s counter-intuitive because we’re taught that corners are "strong," but in this specific defensive setup, a corner move is a death sentence.

The psychology of the draw

When two experts play, it’s boring. It’s a stalemate. This is why computers like the one in the 1983 film WarGames famously concluded that Tic Tac Toe is a game where "the only winning move is not to play." But we aren't computers. We're humans who get bored, blink, and make mistakes.

📖 Related: Grand Theft Auto Games Timeline: Why the Chronology is a Beautiful Mess

Expertise in this game isn't just about knowing the moves; it's about playing fast to induce panic. When you move instantly, you signal to your opponent that you know something they don't. That pressure causes "calculation errors." They start looking at your pieces instead of the empty spaces where the danger actually lies.

A step-by-step roadmap for the first player

If you want a concrete path to victory, follow this logic tree. It’s the closest thing to a guaranteed win against a casual player.

- Take a corner. It doesn't matter which one. Let's say top-left.

- If they take any square EXCEPT the center, you've won. Just take another corner, leaving a space between your two marks. They will be forced to block you. Then, you take a third corner that creates two winning paths.

- If they take the center, things get trickier. You need to take the opposite corner (bottom-right). Now you have a diagonal.

- Watch their next move. If they take a corner, you win by taking the remaining corner to create a fork. If they take an edge, the game will likely end in a draw, provided you both play perfectly.

This isn't just theory. It's been tested by everyone from mathematicians to the programmers who write the AI for "Expert" mode on Google’s own Tic Tac Toe widget. The game is essentially a 3x3 grid of possibilities, totaling 255,168 possible games, but when you account for symmetry, there are only 765 essentially different positions. That's small enough for a human to memorize the "danger zones."

Defensive play: When you're on the ropes

Sometimes you're playing someone who also knows the corner trick. What then? You have to be a pest. Your goal shifts from "winning" to "denying."

- Priority 1: If they have two in a row, you block them.

- Priority 2: If you have two in a row, you complete it.

- Priority 3: If no one is about to win, you block any potential "fork" your opponent might be building.

A lot of players forget Priority 3. They think they're safe because there isn't an immediate row of two. Then—bam—the opponent places a mark and suddenly there are two different rows of two. Game over. To prevent this, always look one move ahead to see where their next fork could happen. If you can occupy that square first, you neutralize the threat.

👉 See also: Among Us Spider-Man: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessed With These Mods

The math of the 3x3 grid

Behind the Xs and Os is a field called combinatorics. Because the board is so small, the game tree is shallow. If you were playing on a 4x4 or 5x5 grid (often called Quarto or Gomoku), the strategies would change because the number of ways to create a fork increases exponentially. But on a 3x3 grid, the "center and corners" strategy is the undisputed king.

Interestingly, if you play randomly, the first player wins about 58% of the time. But once you introduce even a basic understanding of how to win tic tac toe every time, that percentage for the first player jumps to nearly 100% against an untrained opponent. The only thing that stops it is the "Perfect Play" response from player two.

Practical next steps to master the board

To truly never lose again, you need to practice recognizing the "empty" forks. Don't just look at where the pieces are; look at the "L" shapes formed by the empty squares.

- Memorize the "Opposite Corner" Opening: This is the most common way to trap people who think they are being smart by taking the center.

- Practice the "Edge Defense": Spend a few games going second and purposefully letting your opponent take corners so you can practice forcing a draw.

- Run Drills: Use a digital version of the game set to "Impossible" or "Expert." Observe how the AI responds to your corner starts. You'll notice it follows the exact same logic of taking the center and then edges to kill your forks.

Once you stop seeing the game as a series of random moves and start seeing it as a geometric puzzle, you'll find that losing becomes almost impossible. It's less about being "smart" and more about being disciplined enough to follow the optimal path every single time.