Ever tried explaining DNA to a kid or a skeptical friend and realized you're tripping over your own tongue? You get to that point where you need to talk about the "building blocks," but the word nucleotide in a sentence feels like a mouthful of marbles. It's a weird word. It sounds like something from a 1950s sci-fi flick or a lab report that someone forgot to translate into English.

Most people just skip it. They say "DNA bits" or "genetic stuff." But if you’re a biology student, a science writer, or just someone trying to sound smart at a trivia night, you need to know how to drop this term naturally. Honestly, it isn’t as scary as it looks.

Why Nucleotide in a Sentence Matters More Than You Think

Language is tricky. Especially scientific language. If you use a word like nucleotide incorrectly, you don't just look a little silly—you fundamentally change the meaning of the biology you're discussing.

👉 See also: Is 4 hours of sleep a night actually sustainable or just a slow-motion wreck?

A nucleotide isn't just a synonym for DNA. It’s the precursor. It’s the specific chemical unit. Think of it like this: if DNA is a massive skyscraper, a nucleotide is a single, specific brick that has a very particular shape and function. You wouldn't call a brick a "skyscraper," right? Same logic applies here.

Let’s look at a basic example. "Each nucleotide in a sentence describing genetic code represents a specific combination of a sugar, a phosphate, and a nitrogenous base."

See? Not that bad.

But it gets deeper. When researchers like James Watson and Francis Crick were racing to figure out the double helix—with a massive, often uncredited assist from Rosalind Franklin—they weren't just looking at "DNA." They were obsessed with how one nucleotide bonded to another. That specific bond is the heartbeat of life itself. If those nucleotides don't line up, you don't get a human. You get a mess. Or you get nothing at all.

The Anatomy of the Word

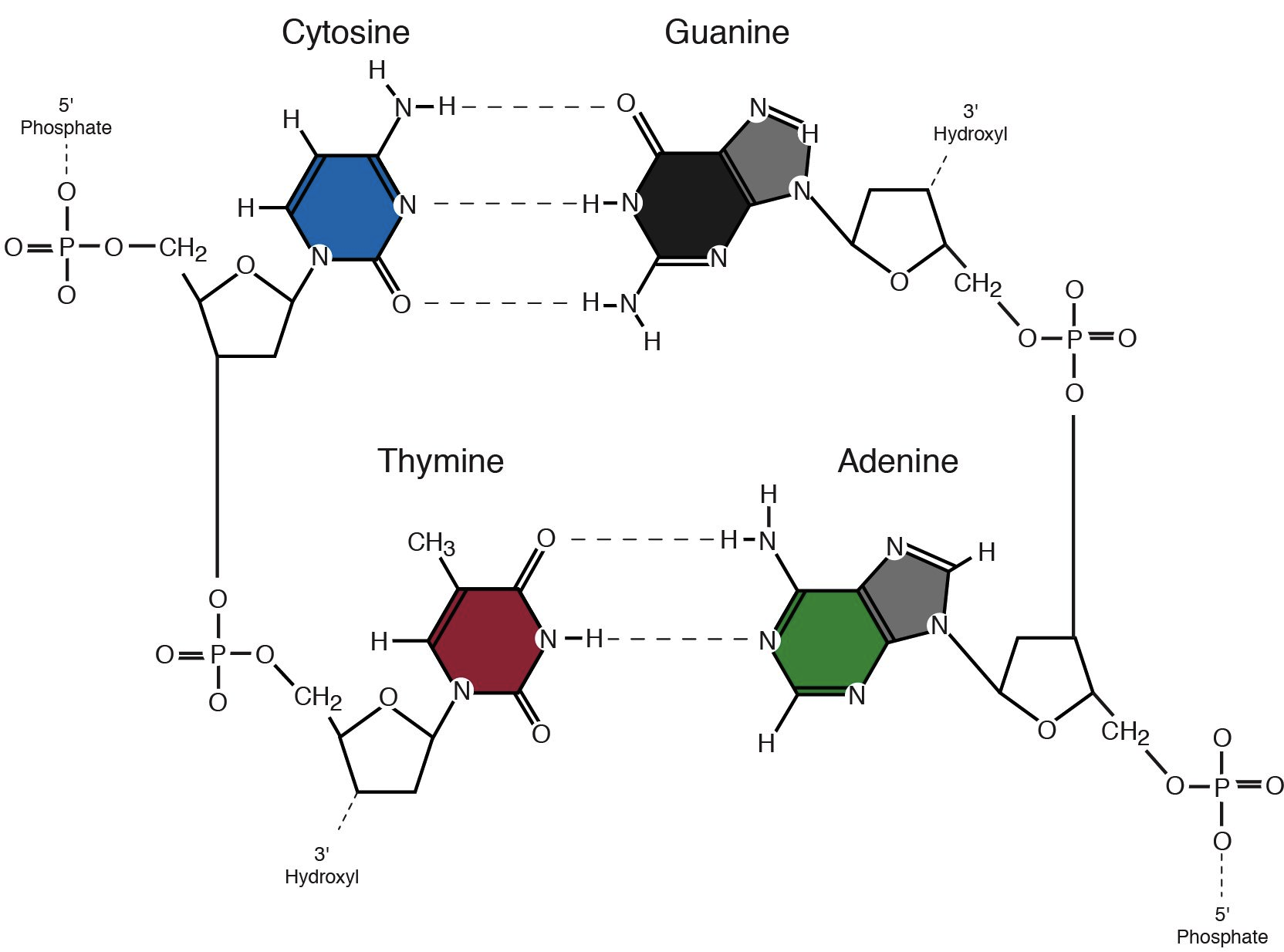

If you're going to use it, you should probably know what's inside it. Every single nucleotide is a trio. It’s a group project where everyone actually does the work. You have the phosphate group, the deoxyribose (or ribose) sugar, and the star of the show: the nitrogenous base.

Those bases—Adenine, Thymine, Guanine, and Cytosine—are the letters of the genetic alphabet. When we talk about "sequencing," we’re really just counting nucleotides.

"The lab technician identified a mutated nucleotide in a sentence of the patient's BRCA1 gene, which suggested an increased risk for specific cancers."

That is a heavy sentence. But it’s accurate. It shows how the word moves from a textbook definition into a real-world medical context. It's not just "science-y" fluff; it’s a precise measurement of a biological reality.

Stop Making These Common Mistakes

People mess this up constantly. They use "nucleotide" and "nucleoside" interchangeably. Big mistake. Huge.

A nucleoside is just the sugar and the base. It’s missing the phosphate. It’s like a car without wheels. It’s there, but it’s not going anywhere. When you add that phosphate group, it becomes a nucleotide, and suddenly it has the energy to build a DNA chain.

Another gaffe? Using it to mean a whole gene.

A gene is thousands, sometimes millions, of these things strung together. Saying "I found a nucleotide for blue eyes" is like saying "I found a letter 'A' for a Shakespeare play." It doesn't make sense. You found a component, not the whole story.

Instead, try: "Researchers observed that a single swapped nucleotide in a sentence of the genetic code can lead to sickle cell anemia."

This highlights the "Point Mutation." It shows that even the smallest unit matters. One wrong letter in a 3-billion-letter book can change the whole plot. It’s terrifying if you think about it too long, but it’s also kind of beautiful.

Context is Everything

You wouldn't use the word "nucleotide" at a grocery store unless you're buying some very specific supplements or talking to a very nerdy cashier.

It belongs in the lab. It belongs in the classroom. It belongs in high-level health discussions.

- In a Lab Report: "The concentration of each free nucleotide in a sentence of the PCR reaction mix must be carefully balanced to ensure successful amplification."

- In a Classroom: "Class, remember that the backbone of the DNA molecule is formed by the sugar and phosphate of the nucleotide, while the bases point inward."

- In a Medical Article: "Synthetic nucleotide analogues are often used in antiviral medications to trick a virus into stopping its replication process."

That last one is super cool. That’s basically how some HIV and Hepatitis C drugs work. They throw a "fake" nucleotide into the mix, the virus tries to use it to build more of itself, and then—clunk—the whole machine grinds to a halt. It’s molecular sabotage.

The Evolution of the Term

We haven't always known what these things were. Back in the late 1800s, Friedrich Miescher first isolated "nuclein" from the nuclei of white blood cells (which he got from pus-soaked bandages—gross, but true). He didn't know he was looking at the foundation of all known life. He just knew it was something rich in phosphorus that didn't act like a protein.

👉 See also: Are Duck Eggs Good for You? The Truth About Nutrition and Flavor

Fast forward to P.A. Levene in the 1920s. He was the guy who actually figured out the structure—the sugar, the phosphate, the base. He coined the term. But he actually thought DNA was a "tetranucleotide," meaning it just repeated the same four units over and over in a boring loop. He thought it was too simple to carry genetic information.

He was wrong about the function, but he was right about the parts.

Later, Erwin Chargaff noticed something weird. The amount of Adenine always matched Thymine. The amount of Cytosine always matched Guanine. This "Chargaff’s Rule" is why we can say: "The pairing of each nucleotide in a sentence of the double helix follows a strict pattern: A with T, and C with G."

Practical Ways to Master the Vocabulary

If you want to get comfortable with this, you have to practice. Not just reading it, but saying it.

- Start by identifying the components in your head. Phosphate. Sugar. Base.

- Use it to describe the "why" of a situation. Why does this test work? Because of the nucleotide sequence.

- Don't over-explain it. In professional writing, you don't need to define it every time. Assume your reader has a baseline.

If you're writing for a general audience, use an analogy first, then drop the term. "DNA is like a twisted ladder. Each rung and the bit of rail it's attached to is called a nucleotide."

It’s about building a bridge between the complex and the relatable.

👉 See also: What Color Is Your Brain? The Surprising Truth About What’s Inside Your Head

Why This Word is Gaining Popularity Again

With the rise of CRISPR and personalized medicine, "nucleotide" is moving out of the basement. People are talking about mRNA vaccines. They're talking about gene editing.

When you hear about an "A" being changed to a "G" to fix a genetic disorder, you're talking about nucleotide substitution. It’s the most precise surgery in the history of the world. No scalpels, just molecular scissors.

"The precision of CRISPR allows scientists to target a specific nucleotide in a sentence of the genome and replace it with a corrected version."

That is the future of medicine. It’s not about drugs that affect the whole body; it’s about fixing the literal code at the most granular level possible.

Final Thoughts on Technical Writing

When you're writing about science, the temptation is to hide behind big words to sound authoritative. Don't do that. The real experts are the ones who can explain the hard stuff simply.

Using nucleotide in a sentence shouldn't be a hurdle. It should be a tool. It’s a word that carries a lot of weight because it represents the fundamental unit of us. Every hair on your head, every beat of your heart, and every thought you're having right now is governed by the sequence of these tiny molecules.

Actionable Steps for Better Science Communication

- Check your nouns: Ensure you aren't using "nucleotide" when you actually mean "nucleoside" or "base pair." A base pair is two nucleotides holding hands; a nucleotide is the individual.

- Vary your verbs: Nucleotides don't just "sit" there. They polymerize, they bond, they mutate, they sequence, and they replicate.

- Contextualize for the reader: If you’re writing for a patient, explain that a nucleotide change is like a "typo" in a recipe. If writing for a peer, focus on the chemical properties.

- Verify the sequence: If you are mentioning specific sequences (like TATA boxes), double-check that you are referring to the nucleotide arrangement and not the protein product.

- Read it aloud: If the sentence feels clunky or you lose your breath halfway through, break it up. Science is dense enough; your prose shouldn't be.