Civil rights litigation is messy. It’s loud, expensive, and historically, it’s been the most effective way to bankrupt hate groups. When people ask about how to sue the klan, they usually aren't looking for a quick settlement or a public apology. They’re looking for a way to use the American legal system to dismantle organizations that rely on intimidation. It’s about hitting them where it actually hurts: the bank account.

The history of this is fascinating. You’ve got figures like Morris Dees and the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) who basically pioneered the "lawsuit as a wrecking ball" strategy. They didn’t just go after the individual person who committed a crime; they went after the leadership. They used vicarious liability. If an organization encourages violence, the organization is responsible for the damages. Simple as that.

The Strategy of Vicarious Liability

Lawsuits against the KKK don’t usually rely on some obscure, dusty law. Most of the time, they use the same principles you'd see in a slip-and-fall case or a corporate negligence suit, just applied to civil rights violations. The heavy hitter here is the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871.

Congress passed this during Reconstruction to stop the KKK from using violence to prevent Black people from voting or holding office. It’s now codified as 42 U.S.C. § 1985. This is the federal "conspiracy" statute. If two or more people conspire to deprive someone of their equal protection under the law, they’re on the hook.

It’s powerful.

But it’s also hard to prove. You have to show there was an actual agreement. You can't just say they're bad people; you have to show they planned the harm together.

Why Beulah Mae Donald Changed Everything

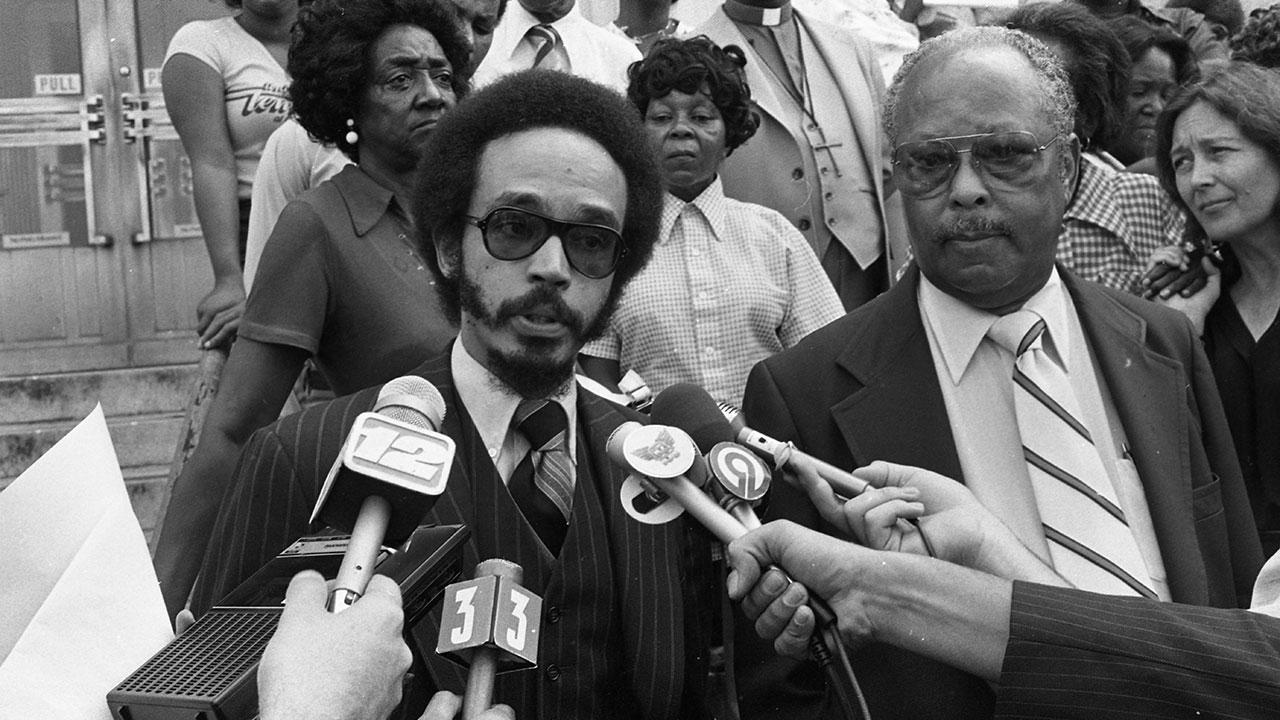

Think back to 1981. Mobile, Alabama. Two members of United Klans of America (UKA) lynched a nineteen-year-old Black man named Michael Donald. It was a horrific, random act of terror intended to "show strength." The murderers were caught, but Beulah Mae Donald, Michael’s mother, didn’t stop at the criminal convictions.

💡 You might also like: The Whip Inflation Now Button: Why This Odd 1974 Campaign Still Matters Today

She sued.

Working with the SPLC, she filed a civil suit against the UKA. The argument was that the organization’s rhetoric and leadership had effectively ordered the killing. The jury agreed. They awarded her $7 million. The UKA didn’t have $7 million. They had to hand over the deed to their national headquarters in Tuscaloosa to satisfy the judgment. That was the end of that specific Klan group. Gone.

How to Sue the Klan Using State Tort Laws

Federal court isn't the only option. Often, state-level "torts" are more effective because the burden of proof is lower than in a criminal case. You aren't trying to put someone in jail—you’re trying to take their assets.

- Assault and Battery: If there was physical contact or the immediate threat of it.

- Intentional Infliction of Emotional Distress (IIED): This is for conduct so "outrageous" that no civilized society should tolerate it.

- Trespass: If they burned a cross on your lawn, that’s a property crime.

- Public Nuisance: Used in some creative cases to argue that a group's presence creates an unsafe environment for the whole community.

Honestly, the "outrageousness" standard for IIED is basically tailor-made for these cases. Klan activity is, by definition, designed to cause extreme emotional trauma.

The Burden of Proof

In a criminal trial, you need "beyond a reasonable doubt." That’s a high bar. In a civil suit, you only need a "preponderance of the evidence." That basically means "more likely than not." If a jury thinks there's a 51% chance the group’s leadership encouraged the violence, you win.

This is why these suits are so terrifying to hate groups. They don't have the same protections they'd have in a criminal dock. They have to sit for depositions. They have to turn over emails, membership lists, and financial records. If they lie, it’s perjury. If they hide documents, it's spoliation of evidence.

📖 Related: The Station Nightclub Fire and Great White: Why It’s Still the Hardest Lesson in Rock History

The Logistics: Finding a Lawyer and Funding

You can't just walk into a local small-claims court and expect to take down a hate group. These cases are marathons. They take years. The discovery phase alone—where you dig through their internal communications—can cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in billable hours and filing fees.

Most people doing this work are non-profits or specialized civil rights firms. The SPLC is the big name, but there’s also the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and more recently, groups like Integrity First for America (IFA).

IFA was the group behind the Sines v. Kessler suit. That was the Charlottesville case. They didn't just sue the guys on the ground; they sued the organizers of the "Unite the Right" rally. They used the 1871 KKK Act. The result? A $26 million verdict. It basically crippled the "alt-right" leadership infrastructure.

What You Need for a Case

If you're serious about this, you need a paper trail.

- Documentation: Screenshots of social media posts, recordings of threats, flyers, or physical evidence of property damage.

- Witnesses: People who saw the intimidation or heard the planning.

- Financial Links: Evidence that the group’s dues or donations were used to facilitate the harm.

It's tedious. It's often scary. But the goal is to make the cost of hate too high to pay.

Misconceptions About the First Amendment

This is where things get tricky. People always scream "Free Speech!" whenever a lawsuit is mentioned. But the First Amendment isn't a magic shield for everything.

👉 See also: The Night the Mountain Fell: What Really Happened During the Big Thompson Flood 1976

You can say hateful things. That’s protected.

You cannot, however, incite "imminent lawless action."

You cannot engage in "true threats."

And you certainly cannot use speech to coordinate a physical attack or a conspiracy to violate someone's civil rights.

Courts have been very clear: the First Amendment does not protect you from the financial consequences of a conspiracy to commit violence. When you're looking at how to sue the klan, you're usually looking for that line where speech turns into conduct. Once they cross that line, the Constitution won't save their bank account.

Practical Steps for Legal Action

If you or a community are being targeted, there's a specific order to how this usually goes.

- Safety First: Contact the FBI and local law enforcement. Even if they don't make an arrest, the police report is a vital piece of evidence for a future civil suit.

- Preserve Everything: Do not delete the harassing emails. Do not wash the graffiti off the wall until it’s been photographed by a professional or the police.

- Contact a Civil Rights Org: Reach out to the SPLC’s legal department or the ACLU. They have intake forms. Be prepared for them to say no—they can only take cases that have the potential to set a major legal precedent.

- Identify the "Deep Pockets": Suing a guy with no job and no assets is a waste of time. You want to sue the organization or the wealthy donors behind them.

- Prepare for Discovery: This is the part where they try to dig into your life, too. It’s a standard intimidation tactic in these suits. You need a lawyer who can protect you from "SLAPP" suits (Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation).

These groups rely on the idea that they are untouchable or that the legal system is too slow to catch them. But history shows that a well-funded, persistent legal team can turn a hate group into a bankrupt memory. Beulah Mae Donald proved it. The Charlottesville plaintiffs proved it.

It’s not about the money. It’s about the fact that it’s very hard to run a hate group when you can’t afford to pay for a website, a meeting hall, or a lawyer.

Actionable Next Steps

- Document every interaction: Use a dedicated log to record dates, times, and specific actions of intimidation.

- Request a "Lethality Assessment": If dealing with local law enforcement, ask for a formal assessment of the threat level to ensure it is prioritized.

- Consult a Civil Rights Attorney: Look for firms that specialize in "Section 1983" or "Section 1985" claims via the National Lawyers Guild or the American Bar Association’s pro bono resources.

- Monitor Financial Ties: If the group is a registered 501(c)(4) or similar entity, public tax filings (Form 990) can reveal their assets and board members, which are essential for naming defendants in a lawsuit.