You’re standing in your backyard. It's dark. You look up, and there it is—a bright, steady point of light hauling across the sky faster than any airplane you've ever seen. That's a football field-sized laboratory orbiting 250 miles above your head. It’s moving at 17,500 miles per hour. Honestly, seeing it for the first time is a bit of a rush, but capturing high-quality photos of the International Space Station is where the real obsession starts. Most people think you need a massive tracking telescope or a job at NASA to get a decent shot. You don't. You basically just need a tripod, a camera that allows manual settings, and a bit of patience.

The ISS doesn't have lights of its own like an airplane does. What you’re seeing is actually reflected sunlight. Because of this, the best time to see it is usually shortly after sunset or right before sunrise. It’s in the sun, but you’re in the dark.

Why Most Photos of the International Space Station Look Like Blurry Streaks

Most beginners end up with a shaky white line that looks like a scratch on the lens. That's because they're trying to track it by hand. Don't do that. Unless you have a specialized, computer-controlled mount like a Sky-Watcher EQ6-R Pro, you aren't going to "track" the station at 17,000 mph and get a sharp image of its solar arrays.

Instead, you have two choices. You can go for the "long exposure streak" which shows the path of the station across the stars, or you can go for "transit photography." Transit photography is the "holy grail." This is when you catch the ISS passing directly in front of the Moon or the Sun. It happens in less than a second. Literally. If you blink, you miss it.

I remember talking to a local astrophotographer who spent three hours setting up for a lunar transit only to have a single cloud drift over the Moon at the exact 0.6 seconds the ISS passed by. That’s the game. It’s high stakes for nerds.

The Gear You Actually Need

Forget the high-end gear for a second. If you have a smartphone, you can get a streak photo. You just need an app that lets you keep the shutter open for 10 to 30 seconds. If you're using a DSLR or mirrorless camera, a wide-angle lens (somewhere between 14mm and 35mm) is perfect for those sweeping shots where the ISS arcs over a landscape.

🔗 Read more: Who is my ISP? How to find out and why you actually need to know

- A sturdy tripod: This isn't optional. If the camera moves a millimeter, the shot is ruined.

- A remote shutter release: Or just use the 2-second timer on your camera so you aren't shaking the device when you press the button.

- Manual focus: Your camera will try to focus on the dark sky and fail. Set it to manual and focus on a distant star or the moon until the light is a sharp pinprick.

Planning the Hunt: When is it Flying Over?

You can't just walk outside and hope for the best. NASA has a great tool called "Spot the Station," but for the real photographers, websites like Heavens-Above or apps like ISS Detector are better. They give you a sky map.

You need to look for the "Magnitude." In astronomy, the lower the number, the brighter the object. An ISS pass with a magnitude of -3.5 is incredibly bright—brighter than Venus. If the magnitude is 0 or 1, it might be too dim to see clearly against light pollution.

Dealing with Light Pollution

If you live in a city like Chicago or London, your sky is orange. It sucks for photos of the International Space Station. The light pollution washes out the contrast. To fix this, you either need to drive an hour away from the city or use a "Light Pollution Filter." These filters specifically block the wavelengths of light emitted by sodium-vapor streetlights.

Capturing the Solar Silhouettes

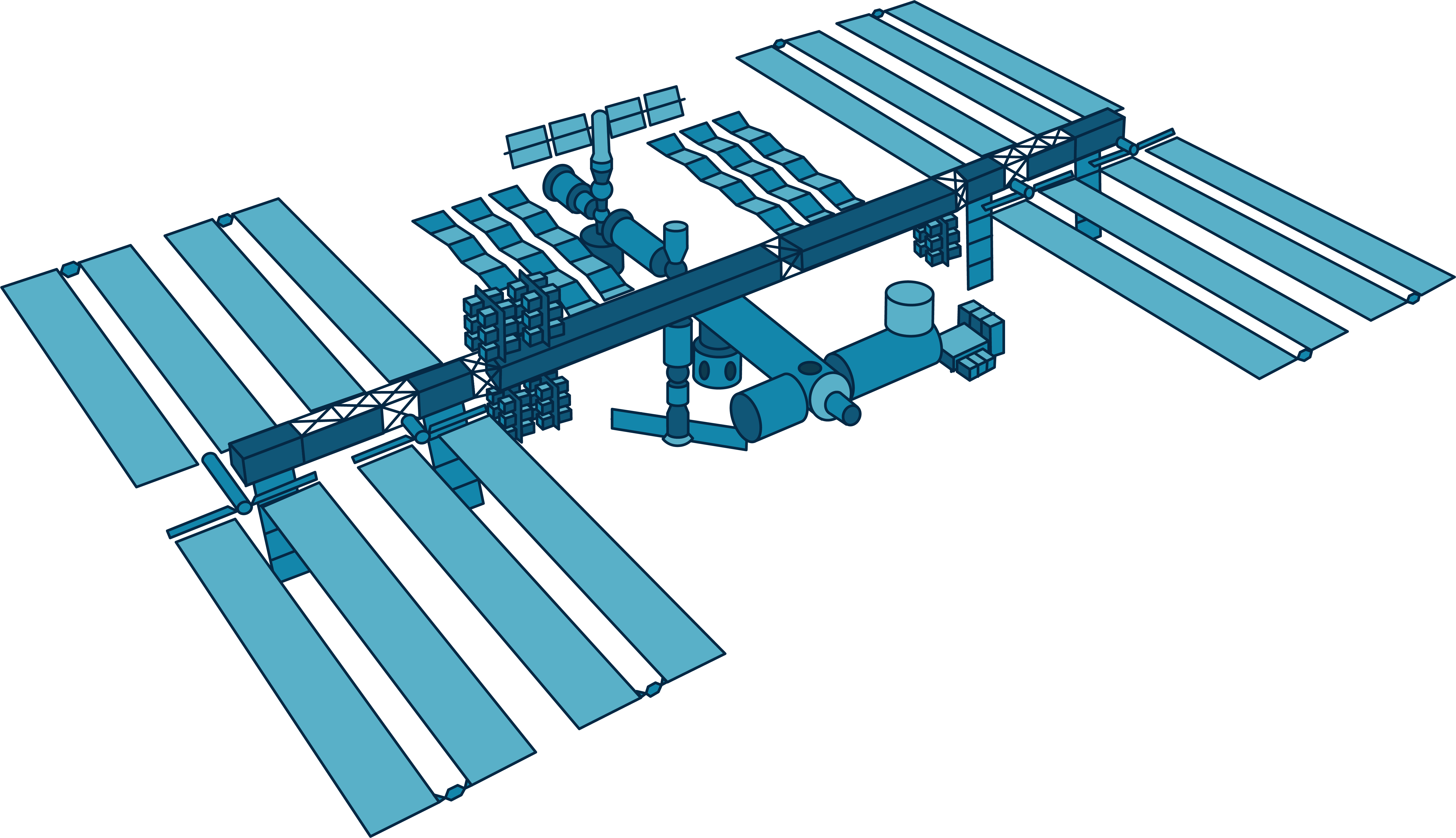

If you want to see the actual shape of the station—the "H" shape of the solar panels—you’re looking at transit photography. This is a different beast. You need a long focal length, at least 600mm or more. People often use "Dobsonian" telescopes for this because they offer huge apertures for a relatively low price.

Thierry Legault is basically the godfather of this. He’s taken photos where you can actually see the Space Shuttle (when it was still flying) docked to the station. To get to that level, you need to use a tool like Transit-Finder.com. You plug in your GPS coordinates, and it tells you exactly where you need to stand. Sometimes, the "path of totality" for an ISS transit is only a few hundred meters wide. You might have to set up your tripod in a random parking lot three towns over just to be in the right spot.

💡 You might also like: Why the CH 46E Sea Knight Helicopter Refused to Quit

Settings for a Lunar Transit

- Shutter Speed: 1/1600th of a second or faster. The station is moving fast. Anything slower and the ISS will be a blur.

- ISO: 400 to 800. You need the sensitivity to keep that shutter speed high.

- Burst Mode: Fire off as many frames as your camera can handle.

The Technical Reality of the ISS

It’s worth noting that the ISS isn't always the same brightness. Its orientation changes. Sometimes the solar panels are angled perfectly to catch the sun and reflect it toward your house; other times, it's significantly dimmer. This is called "flaring."

Also, the altitude varies. Because of "atmospheric drag," the ISS actually loses altitude over time. Every few months, the engines on a docked cargo ship or the station’s own thrusters fire to "re-boost" it. This means the orbital predictions are only accurate for a few weeks at a time. If you’re looking at a schedule from a month ago, it’s wrong.

Common Misconceptions About ISS Photos

I see this a lot on Reddit: someone posts a photo of a blinking light and claims it's the ISS. It's not. The ISS is a solid, non-blinking light. If it's blinking, it’s a plane. If it's a tiny point of light that suddenly disappears in the middle of the sky, you just watched it enter the Earth's shadow. That's actually a cool shot to catch—the "fade out."

Another thing: people think you need a "space camera." While the astronauts on board use modified Nikon Z9s and D6s, you can get a world-class shot with a ten-year-old Canon Rebel if your technique is solid. The atmosphere is your biggest enemy, not your sensor. "Atmospheric seeing"—the turbulence in the air—is why stars twinkle. For the sharpest photos of the International Space Station, you want a cold, still night.

Processing Your Images

Raw photos often look underwhelming. To make them pop, you'll want to use software like Adobe Lightroom or the free version of DaVinci Resolve if you're doing video.

📖 Related: What Does Geodesic Mean? The Math Behind Straight Lines on a Curvy Planet

- Increase Contrast: This makes the black of space look actually black.

- Adjust White Balance: Usually, the sky looks too blue or too brown. Shift the slider until the stars look white.

- Stacking: If you took 20 photos of the ISS moving across the sky, you can "stack" them using a program called StarStacker. This creates one continuous line of light rather than a series of dashes.

The Human Element

We shouldn't forget that there are people on that dot. Usually seven or more. When you’re looking through your viewfinder, you’re looking at a pressurized metal tube where humans are doing heart cell research and combustion experiments in microgravity.

The first "modular" piece of the ISS (Zarya) went up in 1998. It’s been occupied continuously since November 2000. That’s over two decades of humans living off-planet. When you capture a photo of it, you're capturing the most expensive and complex machine ever built. It’s basically a flying monument to what happens when countries stop fighting and start building.

Actionable Steps for Your First Session

Don't go out tonight and try to get a transit. Start small.

- Download ISS Detector (or check Heavens-Above). Find a "Visible Pass" with a magnitude better than -2.0.

- Check the weather. Look for "Transparency" on a site like Clear Outside. If the humidity is high, the sky will be hazy.

- Set up 10 minutes early. Your eyes need time to adjust to the dark.

- Find your focus. Use the brightest star you can see (or Jupiter/Mars). Use your camera's screen to zoom in 10x and turn the focus ring until the dot is as tiny as possible.

- Go wide. Put your lens at its widest focal length. Set an exposure for 20 seconds at f/2.8 or f/4.

- Time it. When the app says the station is appearing in the West, start your exposure.

Once you’ve mastered the long-exposure streak, then you can start worrying about telescopes and solar filters. But for now, just getting a clean, sharp line of light over your own roof is a massive win. It connects you to the people orbiting above in a way that just looking at NASA's official flickr account never will.

The station is slated for decommissioning around 2030. It will eventually be de-orbited and crashed into the Pacific Ocean. You have a limited window in human history to walk out into your yard and photograph this specific marvel. Go do it before it’s gone.