You’ve probably been there. You sit down with a fresh sheet of paper, a 2B pencil, and a vision of a majestic, fluffy bunny. Then, ten minutes later, you’re looking at a lumpy circle with two accidental antennae. It’s frustrating. Honestly, learning how to sketch a rabbit is one of those tasks that seems deceptively simple until you actually try to map out the anatomy of a creature that is basically 80% fur and 20% twitching nerves.

Rabbits aren't just balls of fluff. They have complex skeletal structures. If you look at a Flemish Giant or even a tiny Holland Lop, the way their weight sits on their haunches is specific. Most beginners make the mistake of drawing a "marshmallow" shape. But rabbits have an arched spine, a powerful set of back legs designed for explosive movement, and a skull that is surprisingly angular under those long ears.

Why your first sketch usually fails

It’s the eyes. People always put the eyes in the front of the head, like a human or a cat. Rabbits are prey animals. Their eyes are positioned on the sides of their heads to provide a nearly 360-degree field of vision. If you draw a rabbit looking straight at you with two eyes clearly visible, it's going to look like a weird Pokémon. In profile, you should only see one eye, and it should be high and far back on the skull.

Think about the "gesture" first.

Before you even touch a pencil to paper for a final line, you need to understand the line of action. In a rabbit, this usually follows the curve from the tip of the nose, over the hump of the shoulders, and down to the tuck of the tail. If that curve is stiff, the whole drawing is dead. Professional animators at studios like Disney or Warner Bros.—think about the classic construction of Bugs Bunny or the more realistic Bambi rabbits—always start with these "rhythm lines."

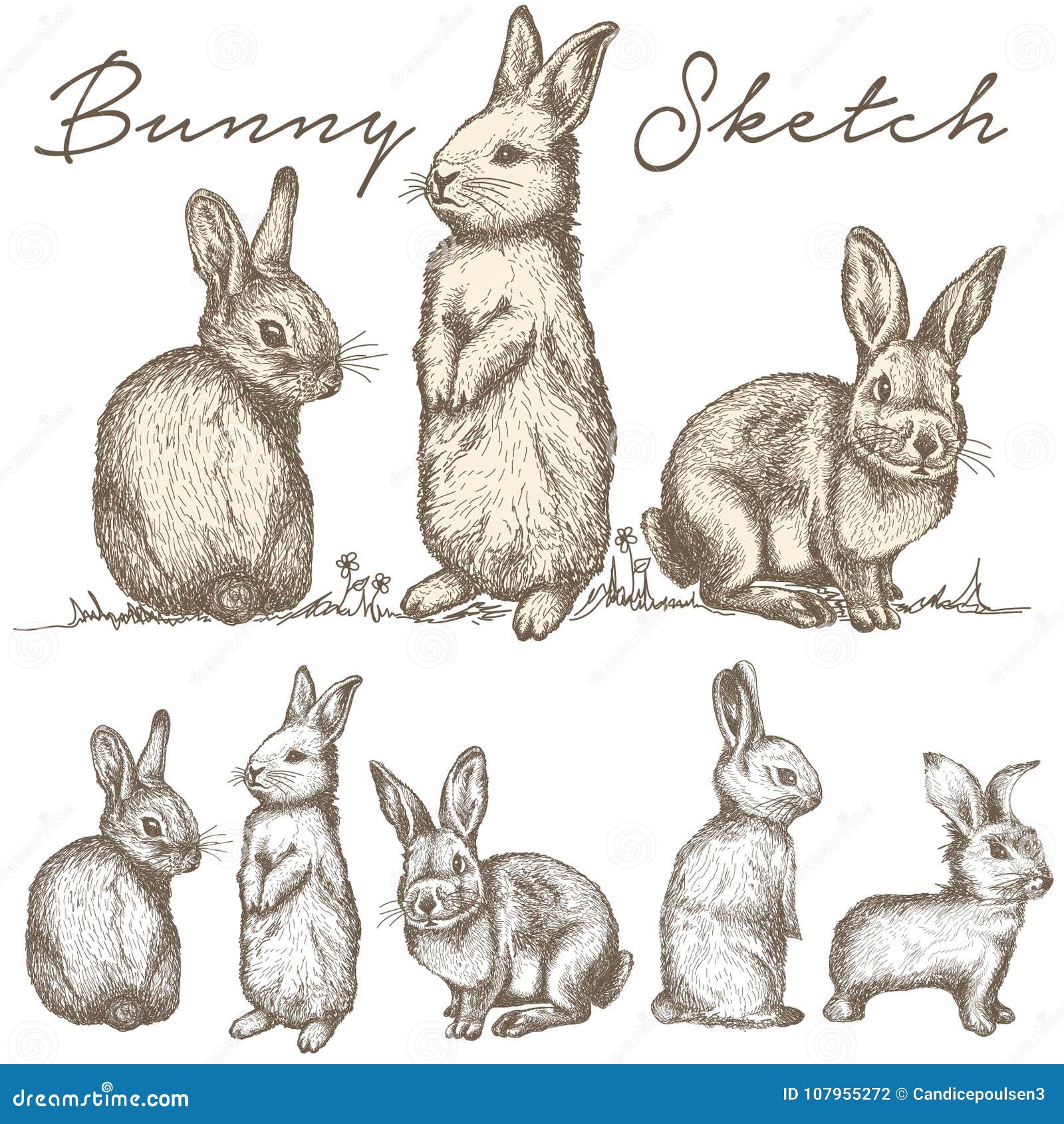

Getting the anatomy right: The three-circle method

Forget the "potato." Instead, try visualizing three distinct circles that overlap.

👉 See also: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

The first circle is the head. It’s the smallest. The second is the chest or "thorax," which sits slightly lower. The third is the largest—the hindquarters. When a rabbit is hunched, these three circles are squeezed together. When it stretches or leaps, they pull apart. This is a fundamental concept in animal drawing often taught by experts like Glenn Vilppu. He emphasizes that "drawing is not about the thing, but the action of the thing."

The ears are not just rectangles. They are delicate, vascular structures. If you look closely at a rabbit's ear, there's a thick "root" where it attaches to the head, and then it fans out. They move independently. One might be cocked toward a sound while the other stays flat. This adds personality. If you draw both ears perfectly parallel, the rabbit looks like a toy, not a living creature.

The secret is in the "tuck"

Look at the back legs. A rabbit’s foot is massive compared to its body size. When they sit, that long foot is tucked right up against the belly. The "knee" is actually hidden under the skin and fur of the torso. What you see as the "elbow" on the back leg is actually the heel. Understanding this "Z-shape" of the skeletal leg will keep your how to sketch a rabbit process from looking lopsided.

Fur is an illusion

Stop drawing every single hair. Just stop.

It’s the fastest way to ruin a sketch. When you're learning how to sketch a rabbit, you should focus on "clumping." Fur grows in groups. Use your pencil to define the shadows under the clumps of fur rather than the hairs themselves. This creates depth. For example, around the neck, rabbits often have a "dewlap"—a fold of skin that looks like a fluffy scarf. Don't draw lines for the fur there; use soft shading to show the weight of the fold.

✨ Don't miss: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

Tools that actually matter

- A 2B or 4B pencil for those dark, rich shadows in the ears and eyes.

- A kneaded eraser. This is non-negotiable. You use it to "pick up" graphite to create highlights in the fur.

- Toned paper. If you use tan or gray paper, you can use a white charcoal pencil for the highlights on the tail and the whiskers. It pops.

A lot of people think they need a massive kit. You don't. You need a steady hand and the ability to look at a reference photo for more than five seconds. Take a look at the work of Beatrix Potter. Her sketches of Peter Rabbit weren't just "cute"; they were anatomically precise because she spent hours studying real lagomorphs. She understood that the weight of a rabbit is concentrated in the back.

Common pitfalls in rabbit sketching

- The nose: People draw a "Y" shape. While that's the basic structure, it's actually a series of soft, moving pads. It's better to suggest it with light shading than hard lines.

- The whiskers: Don't draw them coming out of the nose. They sprout from the "whisker pads" on the cheeks. Use a quick, flicking motion of the wrist. If they are too thick, the rabbit looks like it has a mustache.

- The tail: It’s not a perfect cotton ball. It’s a small, muscular stump covered in fur. It has a top and a bottom. Usually, the underside is lighter.

Putting it all together: A workflow

Start with the "envelope." This is a series of light, straight lines that box in the entire shape of the animal. It helps you get the proportions right before you commit to the curves. If the box is too long, you know your rabbit is going to look like a dachshund. Once the proportions are set, drop in those three circles we talked about.

Connect the circles with a fluid line. This is where you define the "scruff" of the neck and the arch of the back.

When you get to the eye, leave a tiny white "catchlight." This is the reflection of light. Without it, the eye looks flat and "dead." With it, the rabbit looks alive and alert. It’s the single most important mark in the entire drawing.

Variations by breed

Not all rabbits are created equal.

🔗 Read more: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

- The Netherland Dwarf: Has a very round head and tiny ears. Proportions are almost "chibi" by nature.

- The English Lop: The ears are the main event. They should drag on the ground and have a heavy, leathery look.

- The Wild Cottontail: Leaner, longer legs, and more "alert" eyes.

Why sketching from life is different

If you have a pet rabbit, try sketching it while it eats. They stay relatively still for a few minutes. This is called "gesture drawing." You have to work fast. You won't get the details, but you will get the soul of the movement. You’ll notice how their nose never stops moving and how they shift their weight constantly. This energy is hard to capture from a static photo.

Realism isn't about copying a photo. It's about understanding the form. When you understand that a rabbit is a creature of tension—always ready to bolt—your lines will naturally become more dynamic. You'll start to see the "negative space" between the ears and the back. You'll notice how the shadow falls under the belly, grounding the animal so it doesn't look like it's floating on the page.

Final touches and refinement

Once the structure is down, go back in with your darker pencil. Define the "creases" where the limbs meet the body. Use a blending stump (or just your finger, honestly) to soften the shadows on the rounded parts of the body. But be careful. If you over-blend, the drawing becomes "muddy." Keep some of those crisp lines on the edges to maintain the silhouette.

The whiskers should be the very last thing you do. Use a sharpened pencil and a very fast stroke. If you hesitate, the line will be shaky.

Moving forward with your art

Now that you've got the basics of how to sketch a rabbit, the next step is repetition. Draw ten of them. Draw them sleeping, jumping, and grooming. Each pose will teach you something new about how their skin stretches over their muscles.

- Study skeletal diagrams: Look at how the spine connects to the pelvis. It explains the "hump."

- Master the "C" curve: Practice drawing the back in one smooth motion.

- Experiment with texture: Try using a dry brush with some ink to create a "furry" effect on the edges of your sketch.

- Focus on lighting: Place a single lamp near your subject (or use a high-contrast photo) to see how the light wraps around the spherical shapes of the body.

The most important thing is to keep the pencil moving. Don't worry about making a "masterpiece" every time. Most of your sketches will be "throwaways," and that’s perfectly fine. That’s how the muscle memory develops. Eventually, you won't need the three circles anymore; you'll just see the rabbit on the paper before you even start.