You’re standing in a pharmacy in Mexico City or maybe a doctor’s office in Madrid. You’ve got this nagging ache right where your arm meets your torso. You need to explain it. You know the word is hombro, but then you realize language isn't just a 1:1 translation game. It’s never that simple.

Spanish is tricky.

The word for shoulder in Spanish is hombro. That’s the baseline. It’s masculine (el hombro). If you have two, they are los hombros. But if you just stop there, you're going to miss the subtle ways Spanish speakers actually talk about their bodies, their clothes, and even their responsibilities.

Honestly, most learners trip up because they try to use "shoulder" the way we do in English for everything. In English, we "shoulder" a burden. We talk about the "shoulder" of a road. We talk about "cold shoulders." Does hombro cover all that? Not even close.

The Anatomy of El Hombro

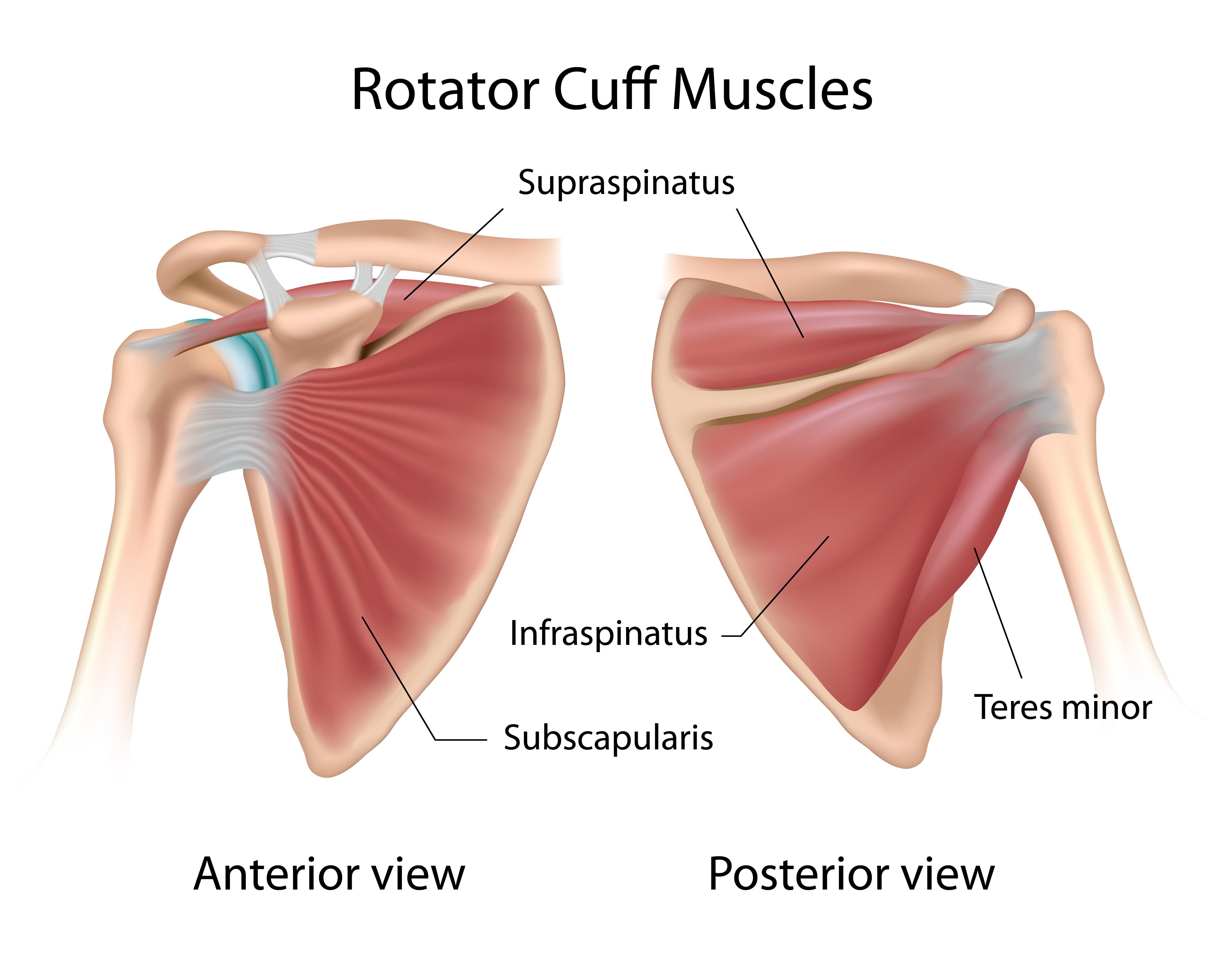

Let's get the basics out of the way first. Anatomically, el hombro refers to the joint and the surrounding muscle. If you’re at the gym and you’re doing overhead presses, you’re working your hombros.

But here’s where it gets specific.

If you are talking about the "shoulder blade," don't you dare say hombro. That’s the omóplato. Or, if you want to sound a bit more "street" or colloquial in certain regions, you might hear paletilla. It’s like the difference between saying "scapula" and "wing bone."

Medical professionals in Spanish-speaking countries are incredibly precise. According to the Real Academia Española (RAE), the term hombro specifically covers the part where the arm joins the trunk. If you’re describing a dislocation to a doctor, you’re talking about a luxación de hombro.

I once saw a student try to describe a "shoulder of ham." They said hombro de jamón. The butcher looked at them like they had two heads. For pigs, we use paleta or paletilla. Using hombro for an animal’s front leg is a fast track to sounding like a confused tourist. It’s those little nuances that separate the fluent from the functional.

When "Shoulder" Isn't Hombro at All

Language is a metaphorical minefield. Think about the road. When you pull over to the side of a highway in Texas, you’re on the shoulder. If you tell a mechanic in Spain that you’re on the hombro, they’ll think you’re standing on a giant’s body.

On the road, the shoulder is the arcén.

In Mexico or parts of Latin America, you’ll hear acotamiento.

In some places, it’s even called the berma.

Context is everything. You have to pivot.

Then there’s the "shoulder" of a garment. If you’re a fashion designer or just someone getting a suit tailored in Bogotá, you might talk about the hombro of the jacket, but the actual shoulder pad is an hombrera. Those giant 80s-style power suits? Those are full of hombreras.

Idioms that actually use the word

Even though many English metaphors don't translate literally, some do.

- Encogerse de hombros: This is literally "to shrink one's shoulders." It means to shrug. If you don't know the answer to a question in a Spanish class, you te encoges de hombros.

- Mirar por encima del hombro: This is a great one. It means to look down on someone. Literally "to look over the shoulder." It implies arrogance. It’s that vibe someone gives you when they think they’re better than you because they’ve mastered the subjunctive mood and you haven't.

- Arrimar el hombro: This translates to "to bring the shoulder close." It means to pitch in or help out. It’s about collective effort. If a neighborhood is cleaning up after a storm, everyone needs to arrimar el hombro.

Regional Slang and Body Parts

Spanish isn't a monolith. The way people talk about their bodies changes once you cross a border. While hombro is universal, the way it’s used in casual conversation varies wildly.

In some Caribbean dialects, people are very expressive with their gestures. A "shrug" might be accompanied by a specific facial expression that says more than the word ever could. In Argentina, you might hear people use more medicalized terms in casual settings, or conversely, very slangy terms for the back and neck area that overlap with the shoulder.

It’s also worth noting the "cold shoulder." In English, you give someone the cold shoulder. In Spanish, you don't use hombro for this. You use hacer el vacío (to create a vacuum/void) or ignorar olímpicamente (to ignore someone in an "Olympic" fashion).

Basically, if you try to say dar el hombro frío, people will just ask if you need a sweater.

The Grammar of Pain

If your shoulder hurts, you don't say "Mi hombro duele."

Well, you can, but it sounds "gringo."

In Spanish, parts of the body aren't usually "owned" with possessive adjectives (my, your, his) when they are the object of an action or a feeling. You use the definite article.

- Me duele el hombro. (The shoulder hurts me.)

- Me lastimé el hombro. (I hurt my shoulder.)

It’s a subtle shift in perspective. The shoulder is a part of the whole, not just a possession. It’s a quirk of the language that reflects a slightly different way of perceiving the self.

I remember talking to a physical therapist in Costa Rica. I kept saying "mi hombro" this and "mi hombro" that. Eventually, he gently corrected me. He said, "We know it's yours, it's attached to you!" It was a funny moment, but it stuck.

Carrying the Weight

When we talk about "shouldering a responsibility," Spanish often moves toward the word cargar (to load/carry) or asumir.

- Cargar con la responsabilidad.

- Llevar sobre los hombros. The second one is more literal. You’ll hear it in religious contexts, especially during Semana Santa (Holy Week) in Spain or Guatemala. The men who carry the massive, heavy floats (pasos) are literally carrying the weight on their shoulders. They are called costaleros in some places, and the physical act of "shouldering" that religious weight is a point of immense pride.

How to use it in a sentence today

If you want to practice right now, try these:

- "Tengo un nudo en el hombro." (I have a knot in my shoulder.)

- "Él me puso la mano en el hombro." (He put his hand on my shoulder.)

- "No te encojas de hombros cuando te hablo." (Don't shrug at me when I'm talking to you.)

Beyond the Basics: Scapulas and Clavicles

If you really want to impress a native speaker, or if you're actually dealing with an injury, you need the surrounding neighborhood of words. The shoulder doesn't exist in a vacuum.

The collarbone is the clavícula.

The armpit is the axila (or more commonly, el sobaco, though that’s a bit more "earthy" and less formal).

The upper back is the espalda alta.

Understanding the relationship between the hombro, the cuello (neck), and the espalda is key for any meaningful conversation about fitness, health, or even just complaining about a long flight in economy class.

Why Getting This Right Matters

You might think, "Who cares? They’ll know what I mean." And sure, they usually will. But language is about connection. When you use the right term for a road's shoulder (arcén) instead of a human shoulder, you're showing that you respect the nuances of the culture. You're showing that you've moved beyond the Duolingo owl and into the real world.

It’s about precision.

📖 Related: High Rise Crop Flare Jeans: Why Most People Are Still Wearing Them Wrong

If you're at a tailor in Mexico City and you say the hombros are too tight, they’ll know what to do. If you tell a doctor your omóplato hurts, they’ll look at your back, not your chest.

Actionable Steps for Mastery

To really lock this in, stop thinking about the word in isolation.

Start by observing your own body. Throughout the day, when you feel tension, say to yourself, "Tengo tensión en los hombros." When you see a car pulled over on the highway, think "Está en el acotamiento."

Next time you watch a show in Spanish—maybe something like La Casa de Papel or a telenovela—pay attention to how they use body language. Look for the encogimiento de hombros. Notice how they use their bodies to emphasize points.

If you're a gym rat, learn your exercises in Spanish. Prensa de hombros. Elevaciones laterales. It changes the neural pathways.

Finally, don't be afraid to make mistakes. If you call a pig's front leg a hombro, and the butcher laughs, laugh with them. Then ask for the paletilla. That's how the word sticks forever.

The goal isn't to be a walking dictionary. The goal is to be a person who can communicate pain, effort, and indifference (the shrug!) in a way that feels natural. Hombro is your starting point, but the context you wrap around it is what makes you fluent.

Go out and use it. Tell someone you’re going to arrimar el hombro on a project. Pull over into the arcén if you need to check your GPS. Just keep the anatomy and the metaphors separate, and you’ll be fine.