So, you’re standing in the middle of a crowded plaza in Madrid, or maybe a dusty street in Oaxaca, and the exhaustion hits. You’re done. The tacos were great, the architecture is stunning, but your feet ache and your brain is fried from trying to conjugate verbs for six hours straight. You need to leave. You need your bed. But when you try to figure out how to say i want to go home in spanish, your mind goes blank.

It happens to the best of us.

Language is weird because the "textbook" version usually makes you sound like a 19th-century diplomat, while the way people actually talk is messy and rhythmic. If you just say "Yo quiero ir a mi casa," sure, people will understand you. But they might also think you’re reading from a primary school primer. Context is everything. Are you telling a friend you're tired at a party? Are you telling a taxi driver where to drop you? Or are you experiencing that deep, existential homesickness that makes you want to hop the next flight to JFK?

The Standard Way to Say I Want to Go Home in Spanish

The literal, most basic translation is Quiero ir a casa.

Simple. Direct. To the point.

In Spanish, the "Yo" (I) is usually dropped because the verb ending -o in quiero already tells everyone you’re talking about yourself. If you include the "Yo," you’re adding emphasis. It’s like saying, "As for me, I want to go home." Use it if you're arguing with friends who want to stay at the club until 6:00 AM.

But "casa" is a flexible word. Sometimes you mean "my house," and sometimes you mean the general concept of "home." If you’re living in an Airbnb or a hotel, saying Quiero ir al hotel is obviously more practical, but if you’re trying to express the sentiment of returning to your sanctuary, casa is the move.

Why the Verb "Irse" Changes Everything

Most beginners learn ir (to go). But native speakers love irse (to leave/to go away).

If you say Me quiero ir a casa, you are adding a layer of "getting out of here." The "me" attached to the verb makes it reflexive, focusing on the act of departing. It’s the difference between saying "I want to go home" and "I want to get myself home." It sounds much more natural. Honestly, if you use me quiero ir instead of just quiero ir, you’ll immediately sound 40% more fluent.

Different Flavors of Leaving

Life isn't a textbook. You aren't always just "going home." You're escaping, you're retreating, or you're just done with the night.

🔗 Read more: Why an Escape Room Stroudsburg PA Trip is the Best Way to Test Your Friendships

Ya me voy. This means "I'm leaving now." It’s the classic phrase used when you’re standing up, grabbing your coat, and heading for the door. It implies the destination (home) without having to say it.

Me retiro. This is a bit more formal, almost like saying "I shall retire for the evening." It’s great if you’re at a nice dinner or a professional event and want to sound classy while exiting.

Tengo ganas de volver. This translates to "I feel like going back." It’s less about the physical movement and more about the desire. If you’re talking about your home country while on a long trip, this is the phrase you use.

Me piro. Warning: this is very slangy, mostly used in Spain. It’s like saying "I'm bouncing" or "I'm outta here." Use it with friends, never with your mother-in-law.

Dealing with Homesickness and "Extrañar"

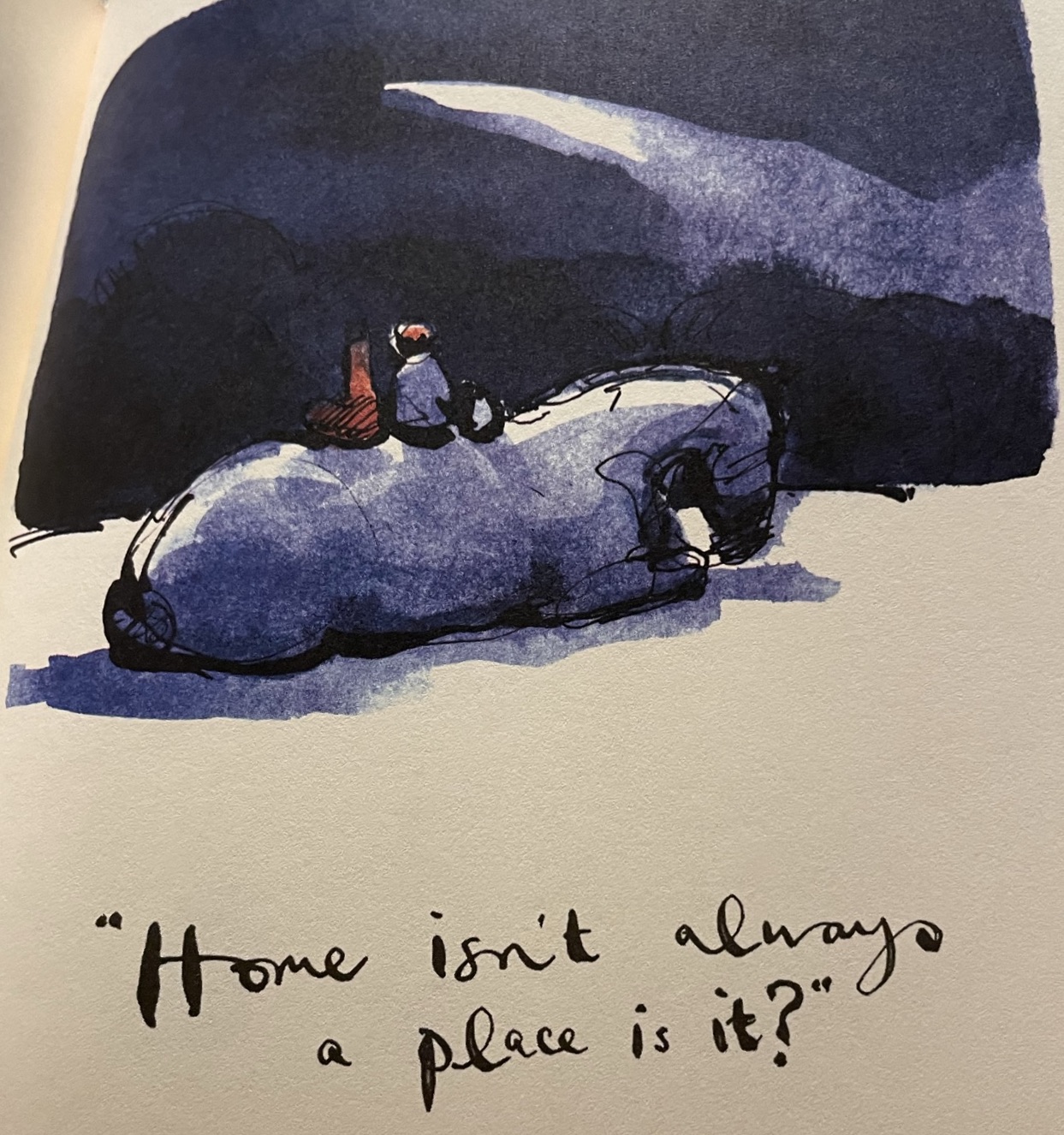

Sometimes, i want to go home in spanish isn't about leaving a party. It’s about the soul-crushing realization that you miss your dog, your own pillow, and a grocery store where you actually know what the cereal boxes say.

In Latin America, you’ll hear Extraño mi casa. In Spain, it’s more likely to be Echo de menos mi casa.

Both mean "I miss home."

There is a psychological weight to these phrases. According to sociolinguists like Dr. Carmen Silva-Corvalán, the way we express "home" reflects our emotional connection to space. In Spanish-speaking cultures, casa isn't just a building; it's the family unit. When you say you want to go home, you might be saying you miss your people.

The "A Casa" vs. "Hacia Casa" Distinction

You might see hacia casa in books. It means "towards home."

💡 You might also like: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Nobody says this in casual conversation.

If you tell a taxi driver "Voy hacia casa," he’ll think you’re a character in a Netflix period drama. Just stick with a casa. Prepositions in Spanish are notoriously tricky—just ask anyone struggling with por vs para—but for going home, a is your best friend. It’s the destination. It’s the end of the line.

Real-World Scenarios

Imagine you’re at a wedding in Mexico. The mariachi band is on their fourth hour. You’ve had three tequilas. You look at your partner and whisper: "Ya me quiero ir a la casa." The addition of la (the) before casa can sometimes make it feel more specific to the place you are currently staying.

Or imagine you are a study abroad student. It’s been three months. You’re sitting in a cafe in Buenos Aires, and you’re crying over a cold empanada. You call your mom. You don't say "Quiero ir a casa." You say "Quiero volver." (I want to return). The verb volver carries the weight of the journey. It implies a return to where you belong.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Don't say "Quiero caminar a casa" unless you are literally walking at that moment.

Don't use "Hogar" in casual speech. Hogar means "hearth" or "home" in a poetic, sentimental sense. You’ll see it on "Home Sweet Home" signs (Hogar Dulce Hogar), but you don’t tell a friend "I’m going to my hogar." It sounds weird. Like you're about to go light a ceremonial fire in your living room.

Regional Variations You Should Know

Spanish is not a monolith. The way you say you want to go home in Medellin is different from how you’d say it in Barcelona.

In Argentina and Uruguay, they might use "Me voy para las casas." It’s a pluralized, colloquial way of saying "I’m heading home." It feels cozy and rural.

In parts of the Caribbean, people talk fast. Everything gets clipped. "Me voy pa' casa" is the standard. That pa' is a shortened version of para. It’s the "wanna" or "gonna" of the Spanish world. If you can drop that ra and slide the words together, you’ll sound like you’ve lived in San Juan for a decade.

The Grammar of Desire: Querer vs. Quisiera

When you say i want to go home in spanish, you’re using the verb querer.

📖 Related: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

Quiero is "I want." It’s a demand.

Quisiera is "I would like." It’s a wish.

If you’re talking to yourself or a close friend, quiero is fine. If you’re talking to a host and want to be polite about wanting to leave, use "Me gustaría irme a casa" (I would like to head home). It softens the blow. It’s less "I’m bored" and more "I’m tired but thank you for the lovely evening."

A Note on "A Casa" vs. "En Casa"

One of the most frequent errors for English speakers is mixing up "to" and "at."

- Voy a casa = I am going home.

- Estoy en casa = I am at home.

If you say "Quiero ir en casa," you’re essentially saying "I want to go (while being inside) home." It makes no sense. The a indicates motion. The en indicates location. Think of a as an arrow and en as a box.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Trip

If you find yourself needing to express this, don't overthink the conjugation.

- Memorize "Me quiero ir." This is your emergency exit phrase. It works for leaving home, leaving a restaurant, or leaving a bad date.

- Use "Ya" for emphasis. Adding ya (already/now) to the start of the sentence—"Ya me quiero ir"—signals that you have reached your limit.

- Watch the tone. Spanish is a tonal language in terms of emotion. If you say it with a smile, it’s a casual exit. If you say it with a sigh, it’s homesickness.

- Practice the "R" in Quiero. It’s a single tap of the tongue, not a rolled R. If you roll it, you’re saying "Quierro," which isn't a word.

When you finally get back to wherever you're staying, you can drop your bags, fall onto the bed, and exhale: "Por fin en casa." (Finally home). That’s the best feeling in any language.

The most important thing is to stop worrying about being perfect. Native speakers are generally thrilled you're even trying. If you mix up ir and irse, the world won't end. You'll still get your taxi. You'll still find your bed. You'll still get that much-needed sleep.

Now, take these phrases and use them. Start by saying them out loud to yourself in the mirror. Get the "m" in me and the "q" in quiero to flow together. Before you know it, you won't be translating in your head anymore. You'll just be speaking. And that's when the real fun of travel—and the relief of going home—truly begins.