You're sitting there, maybe feeling a little dizzy or just "off," and you see the number. Your systolic—the top number—looks fine, but that bottom number is dragging. It’s sitting in the 50s or low 60s. You want to know how to raise diastolic blood pressure instantly because, honestly, having a wide pulse pressure feels weird. Your heart is thumping, but your head feels light.

Low diastolic pressure, or isolated diastolic hypotension, is a sneaky one. While the medical world obsessively talks about high blood pressure, having a bottom number that's too low can starve your heart muscle of oxygen. Why? Because the coronary arteries actually fill up when the heart is resting—which is exactly what that diastolic number represents. If there isn't enough "back pressure" in the system, the heart doesn't get its own fuel.

The Quick Fixes That Actually Work

If you need a bump right now, the fastest way is through immediate fluid and salt intake. It’s basic physics. Your circulatory system is a series of pipes. If the pressure is low, you need more volume in the pipes. Drink a large glass of water—about 16 ounces—and pair it with something salty like a handful of olives, a cup of bouillon, or even just a pinch of sea salt under the tongue.

Research published in the journal Circulation has shown that water drinking can have a significant pressor effect in people with autonomic failure or low blood pressure. It’s not a permanent cure, but it’s an instant physiological lever.

Movement helps too. Don't just sit there staring at the monitor. If you're lying down, pump your ankles. Cross your legs tightly while sitting. These "physical counter-pressure maneuvers" squeeze the blood out of the veins in your legs and push it back toward your heart and brain. It's a trick fighter pilots use to avoid blacking out during high-G maneuvers, and it works for a low diastolic reading just as well.

📖 Related: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

Why Your Bottom Number Is Low to Begin With

Sometimes, your diastolic pressure is low because your arteries are too "stiff." As we age, or if we have certain types of cardiovascular disease, the aorta loses its elasticity. Normally, the aorta acts like a balloon—it stretches when the heart pumps (systolic) and then snaps back to keep blood flowing when the heart rests (diastolic). If the aorta is stiff, it doesn't snap back. The pressure just drops off a cliff the second the heart stops squeezing.

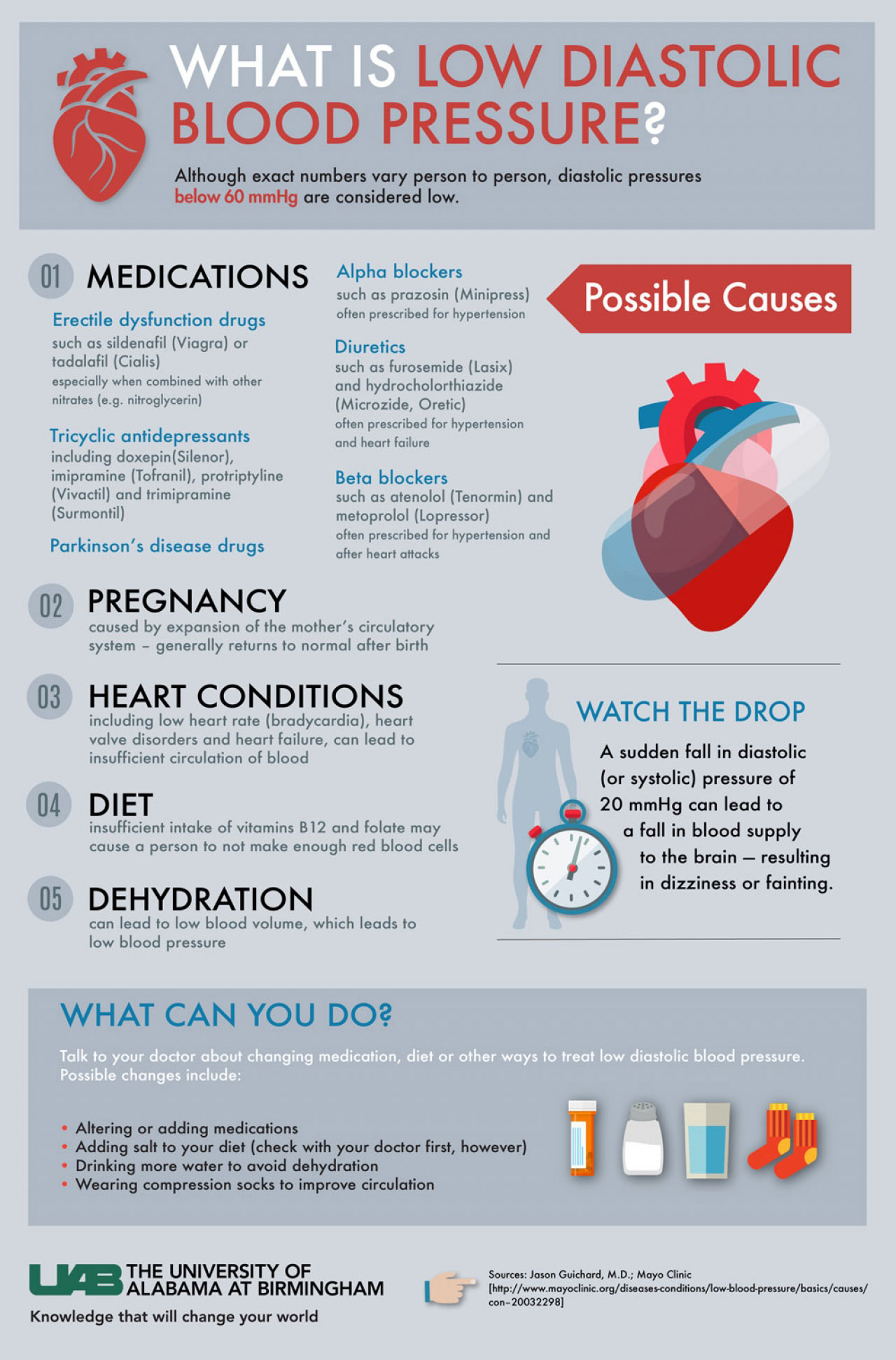

Another culprit? Medications. You might be taking an alpha-blocker or a diuretic that’s doing its job a little too well. Or maybe it's your thyroid. An underactive thyroid (hypothyroidism) or an overactive one (hyperthyroidism) can both mess with how your blood vessels constrict and relax.

Then there's the lifestyle stuff. Are you dehydrated? Truly dehydrated, not just "I haven't had water in an hour" dehydrated? When your blood volume drops, the diastolic pressure often takes the hit first.

The Alcohol Factor

Alcohol is a weird one. Initially, it might make you feel warm and flushed because it's a vasodilator. It opens up the "pipes." This can cause your diastolic pressure to tank shortly after drinking. While long-term heavy drinking is linked to high blood pressure, that immediate window after a couple of drinks often sees a dip that can make you feel lightheaded when you stand up. If you're looking for how to raise diastolic blood pressure instantly, skipping the evening glass of wine is a good start.

👉 See also: Ankle Stretches for Runners: What Most People Get Wrong About Mobility

Understanding the Risks of "Isolated" Low Pressure

We used to think the lower the better. That’s not really the case anymore. The J-curve phenomenon suggests that if you push diastolic pressure too low—specifically below 60 mmHg—the risk of heart attacks and strokes might actually go up, especially in people who already have coronary artery disease.

Dr. Sahil Parikh from Columbia University Irving Medical Center has noted in various clinical contexts that while we focus on the "top" number to prevent strokes, the "bottom" number is vital for heart perfusion. If you're a "60-something" or "70-something" person with a systolic of 130 and a diastolic of 55, your heart might be working harder than it needs to.

Long-Term Strategies That Move the Needle

You can’t just eat salt and cross your legs forever. To stabilize your diastolic pressure, you have to look at vascular tone.

- Strength Training. Everyone talks about cardio, but resistance training helps improve the "tone" of your blood vessels. It makes them more responsive.

- Reviewing Meds. Sit down with your doctor and look at your ACE inhibitors or calcium channel blockers. Sometimes a slight dose adjustment is all it takes to bring that bottom number back into the "safe zone" of 70–80 mmHg.

- Compression Stockings. They aren't just for airplanes. If your blood is pooling in your legs due to venous insufficiency, your diastolic pressure will suffer. Waist-high or thigh-high compression (20-30 mmHg) can provide that external pressure your veins are failing to provide.

- Hydration with Electrolytes. Plain water is fine, but water with sodium, potassium, and magnesium is better. It stays in the vascular space longer rather than just running straight to your bladder.

The Role of Stress and the Nervous System

Your autonomic nervous system is the conductor of this whole orchestra. If you are stuck in a "freeze" state or have a condition like POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome), your body struggles to regulate pressure when you change positions. In these cases, raising diastolic pressure isn't just about salt; it's about retraining the nervous system.

✨ Don't miss: Can DayQuil Be Taken At Night: What Happens If You Skip NyQuil

Deep, slow "box breathing" can sometimes help normalize the system, though it’s more commonly used to lower high pressure. For low pressure, you actually want a bit of "activation." A cold splash of water on the face—the mammalian dive reflex—can cause an immediate peripheral vasoconstriction, which kicks the diastolic pressure up a few notches.

When to Stop Troubleshooting and See a Pro

Look, if your diastolic is consistently below 60 and you feel like a zombie, stop DIY-ing it.

If you’re experiencing chest pain, extreme shortness of breath, or fainting spells, that's not a "drink more water" moment. That's an ER moment. Low diastolic pressure can be a sign of a leaking heart valve (aortic regurgitation) or severe anemia. No amount of olives will fix a structural heart issue or a lack of red blood cells.

Practical Steps to Take Right Now

If you've just taken your pressure and the diastolic is low, do this:

- Drink 500ml of cold water immediately. Cold water has been shown to have a slightly stronger pressor effect than room temperature water.

- Eat a high-sodium snack. Think pickles, soy sauce, or salted nuts.

- Put on compression socks if you have them.

- Lie down and elevate your feet above your heart for 10 minutes, then stand up very slowly.

- Track the trend. One low reading is a fluke. Five days of low readings is a pattern you need to bring to your primary care physician.

Most people find that by simply increasing their salt and fluid intake and adjusting their movement patterns, that stubborn bottom number starts to climb back into a healthy range. It’s about finding the balance between "relaxed" arteries and "collapsed" ones.

Next Steps for Stability:

Schedule a blood panel to check your ferritin (iron) and B12 levels, as deficiencies here can often mimic or contribute to low blood pressure symptoms. Additionally, perform a "poor man's tilt table test" at home: measure your blood pressure after lying down for 5 minutes, then again after standing for 2 minutes. If the diastolic drops significantly upon standing, discuss the results with a cardiologist to rule out orthostatic hypotension.