Everyone thinks they know how to squat until they're staring at a barbell with fifty pounds of iron on each side and their lower back starts screaming. It’s the king of exercises. You've heard that a million times, right? But honestly, most people in your local gym are doing it in a way that’s basically a slow-motion car crash for their joints.

Squatting isn't just about bending your knees. It’s a complex coordination of your ankles, hips, and spine working in a symphony that most of us have forgotten how to play because we spend eight hours a day sitting in cheap office chairs. If you want to learn how to properly do a squat, you have to stop thinking about "going down" and start thinking about "opening up."

👉 See also: Total Cereal Nutrition: Is This 1950s Staple Actually a Superfood?

The Myth of the Perfect Form

There is no such thing as a universal "perfect" squat. If someone tells you your feet must be shoulder-width apart and pointing exactly forward, they’re probably ignoring basic human anatomy. Look at the neck of a femur. Some people have deep hip sockets; others have shallow ones. Some have long femurs that make them look like folding lawn chairs when they descend. Basically, your "perfect" stance is dictated by your bone structure, not a checklist from a 1980s aerobics video.

To find your footprint, try this: jump in the air and see where your feet land naturally. Usually, that’s your power position. For most, it’s a bit wider than the hips with the toes turned out about 15 to 30 degrees. This creates space for your pelvis to drop between your thighs rather than crashing into your hip bones.

The Setup: Where 90% of Failures Happen

The squat begins before you even move. If you're using a barbell, the "unrack" is your foundation. You need to create a "shelf" for the bar. High-bar squatters place it on the upper traps, while low-bar squatters—often powerlifters—tuck it across the rear deltoids. If the bar is resting on your neck bones, you're doing it wrong and you're going to hurt yourself.

Bracing is the secret sauce. You aren't just "sucking in your gut." You need to breathe into your belly—a technique called the Valsalva maneuver. Think about someone is about to punch you in the stomach. You tighten your core, create internal pressure, and turn your torso into a rigid cylinder. This protects your spine. Without this pressure, your back will round like a frightened cat the moment things get heavy.

The Descent and the "Tripod Foot"

Focus on your feet. You want three points of contact: your heel, the base of your big toe, and the base of your pinky toe. Imagine your feet are claws grabbing the floor. As you start to descend, don't just sit back. Think about "screwing" your feet into the ground. This creates external rotation in the hips, which keeps your knees from caving in—a common error known as knee valgus.

Knees over toes? Let's settle this. For decades, "experts" said your knees should never pass your toes. That’s mostly nonsense. If you have long legs, your knees have to go past your toes to keep your center of gravity over your mid-foot. If you force them to stay back, you'll lean too far forward and put massive shear stress on your lower back. As long as your heels stay on the ground and your knees aren't wobbling like Jell-O, you're fine.

💡 You might also like: How Long Do Edibles Stay in Your Urine? The Reality of Drug Testing Timelines

Depth: How Low Should You Actually Go?

"Ass to grass" looks cool on Instagram, but it’s not for everyone. The goal is to reach "parallel"—where the crease of your hip is level with or slightly below the top of your kneecap.

- The Butt Wink: This is the dreaded posterior pelvic tilt. If you go too low and your tailbone starts to tuck under, you're losing tension in your hamstrings and putting your lumbar discs at risk.

- Mobility Gates: If you can't hit depth, it's usually not a strength issue. It's often tight ankles. If your ankles don't flex (dorsiflexion), your heels will pop up.

- Shadow Testing: Use a mirror or film yourself from the side. If your back rounds before you hit parallel, stop there. That's your current "functional depth." You can work on the rest later.

Why Your Lower Back Hurts

If you finish a set of squats and your lower back feels pumped or painful, you're likely "stripper squatting." This happens when your hips rise faster than your chest on the way up. It turns the squat into a "good morning" exercise, shifting the entire load onto your spine.

To fix this, think about driving your traps back into the bar as you push out of the "hole" (the bottom of the squat). Your hips and shoulders should rise at the exact same rate. It’s a total-body push, not a leg press followed by a back extension.

Equipment and Nuance

Do you need lifting shoes? Maybe. If you have poor ankle mobility, the raised heel of a weightlifting shoe can be a game-changer. It essentially "cheats" the ankle range of motion, allowing you to stay more upright. But don't rely on them forever. Work on your calf flexibility.

Belts are another point of contention. A lifting belt doesn't "support" your back; it gives your abs something to push against to create more internal pressure. If you can't squat 135 pounds with a flat back without a belt, you shouldn't be wearing one yet. Build the internal brace first.

Common Mistakes Breakdown

- The Toe Rise: If your weight shifts to your toes, you're losing power and risking your ACL. Keep the weight mid-foot.

- Looking Up: Don't stare at the ceiling. It kinks your neck and messes with your spinal alignment. Pick a spot on the floor about six feet in front of you and keep your gaze there.

- The "Soft" Top: Finish the rep. Stand all the way up and squeeze your glutes, but don't hyperextend your lower back at the top.

How to Properly Do a Squat: The Progression Path

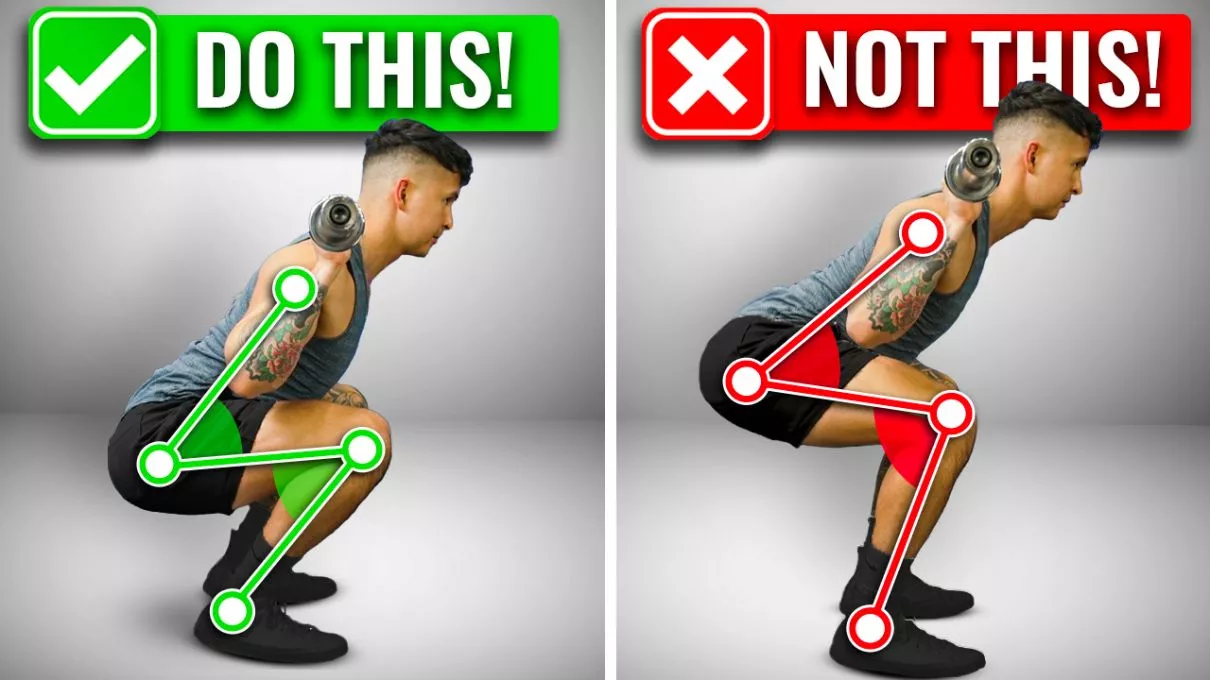

If you're a beginner, don't touch a barbell yet. Start with the Goblet Squat. Hold a dumbbell or kettlebell against your chest. This weight acts as a counter-balance, making it much easier to sit deep and keep your chest up. Once you can do 20 clean goblet squats with a heavy weight, then you’ve earned the right to go to the rack.

Dr. Stuart McGill, a leading expert on spine biomechanics, often suggests that for many people, the back squat isn't even necessary. Front squats or split squats can build massive legs with much less spinal compression. But if you want to back squat, you have to respect the movement. It’s a skill, just like throwing a football or playing the piano. You don't just "do" it; you practice it.

The Actionable Plan

To actually master this, stop chasing heavy weights for a few weeks and focus on the mechanics.

- Warm up your ankles: Spend 2 minutes doing knee-to-wall stretches to improve dorsiflexion.

- Activate your glutes: Do a set of bird-dogs or glute bridges before you get under the bar. This wakes up the muscles that are supposed to be doing the heavy lifting.

- Pause Squats: Take a light weight, go to the bottom of your squat, and hold it for 3 seconds. This forces you to find your balance and removes the "bounce" that often hides bad form.

- Record yourself: Your brain lies to you. You think you're hitting parallel, but you're probably four inches high. The camera doesn't lie.

Start your next leg day with three sets of five reps at 50% of your usual weight. Focus entirely on the "tripod foot" and the belly breath. If you can't feel your core working as hard as your quads, you're not bracing enough. Tighten up, sit down between your knees, and drive the floor away. That is how you build real strength without the doctor's visits.