So, you’re stuck with a 3D cell model project plant assignment. It usually happens around 7th or 10th grade, and honestly, it’s a bit of a rite of passage in science class. Most people panic and head straight to the craft store to buy those overpriced Styrofoam spheres. Don't do that. It's boring. It's also technically incorrect because plant cells aren't round—they have rigid walls. If you show up with a basketball-shaped plant cell, your teacher is going to know you didn't really get the concept of turgor pressure.

Why the Shape of Your 3D Cell Model Project Plant Actually Matters

Biology isn't just about memorizing names; it's about architecture. A plant cell is basically a fortress. Unlike animal cells, which are squishy and flexible, plant cells need to hold up the weight of the entire organism. Think about a giant redwood tree. It doesn't have a skeleton. It stays upright because every single cell is encased in a rigid wall made of cellulose.

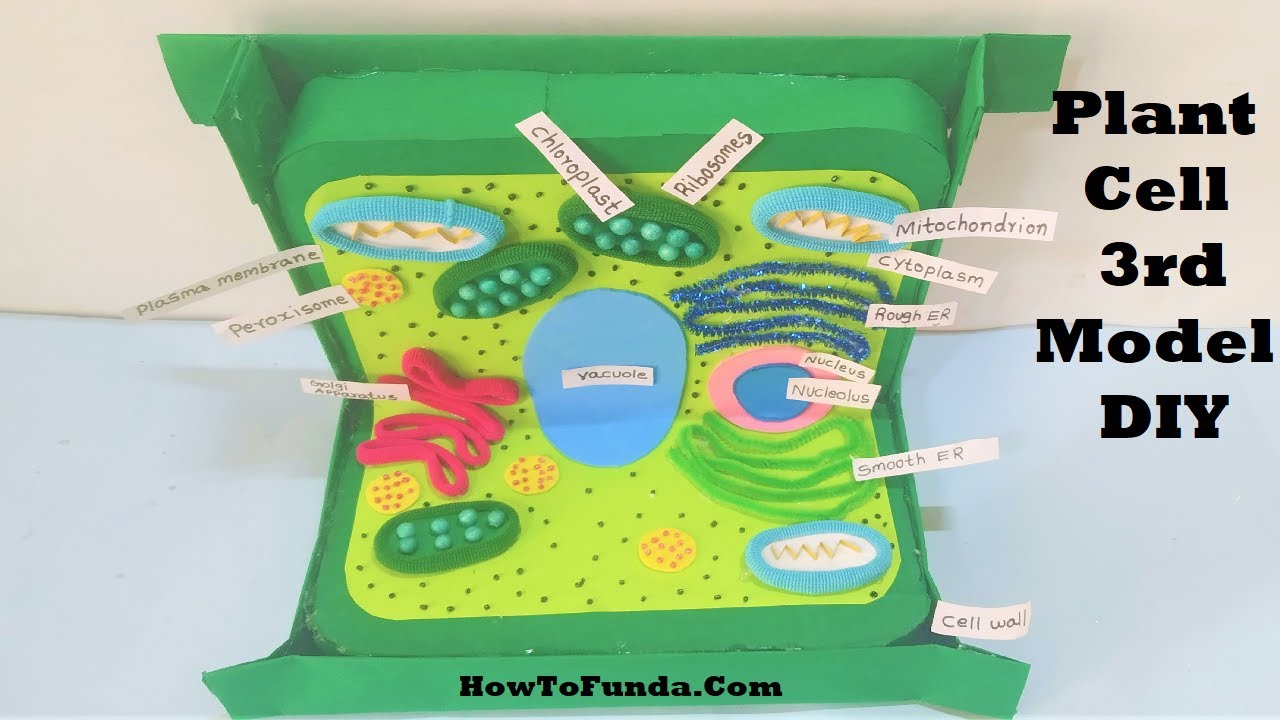

When you start your 3D cell model project plant, your first job is finding a rectangular or hexagonal container. A shoebox is the classic choice, but a clear plastic storage bin or even a deep baking dish works better if you want to show off the "cytoplasm" inside.

If you use a shoebox, you're representing the cell wall. It’s the outermost layer. Just inside that, you need a thin lining—maybe some construction paper or a layer of plastic wrap—to represent the cell membrane. In plants, the membrane is pushed right up against the wall because of water pressure. It’s tight. If your model has a big gap between the wall and the membrane, your cell is technically "plasmolyzed," which means it's dying of thirst. Probably not the vibe you want for an A+.

The Big Three: Vacuoles, Chloroplasts, and Nuclei

Most people mess up the scale. In a plant cell, the Central Vacuole is the absolute king. It’s not just a little bubble; it can take up to 90% of the cell's volume. It’s basically a massive water balloon that keeps the cell stiff. If you're building a model, use a literal water balloon or a large, clear Ziploc bag filled with blue hair gel. It looks cool, and it accurately shows how it pushes all the other organelles (the "little organs") against the edges.

🔗 Read more: Why Everyone Is Still Obsessing Over Maybelline SuperStay Skin Tint

Then you've got the Chloroplasts. These are the solar panels. You need a lot of them. They are green because of chlorophyll, obviously, but they also have a very specific internal structure called thylakoids—stacks of discs. You can mimic these using green buttons or even stacked pennies painted green. Just throwing in a few green lima beans is fine, but if you want to look like an expert, show that internal texture.

The Nucleus is the brain, containing the DNA. In an animal cell, it sits right in the middle. In your 3D cell model project plant, the nucleus usually gets shoved to the side because that giant vacuole is hogging all the space. Use a Stress ball or a large plum. If you cut it in half, you can show the "nucleolus" inside, which is where ribosomes are born.

Making the "Guts" Look Realistic

The cytoplasm is the jelly-like stuff that fills the gaps. Some kids use lime Jell-O. It’s a classic move, but it’s a nightmare to transport to school. It melts. It smells after two days. It leaks. Honestly, clear hair gel or even just unflavored gelatin (made with less water so it’s extra firm) is a better bet. If you want a "dry" model that won't rot, use spray foam from the hardware store. It expands to fill the box and has a weird, organic texture that looks surprisingly like cellular fluid once you paint it.

Don't forget the weird stuff:

- Mitochondria: The "powerhouse" (everyone says that, it’s a law). Use dry pasta shapes like rotini. Paint them red. They have a wavy internal membrane called cristae, and the spiral shape of pasta captures that perfectly.

- Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER): This is the transport system. The Rough ER has ribosomes on it, so use some folded ribbon or felt and sprinkle it with black pepper or glitter. The "smooth" ER doesn't have the bumps.

- Golgi Apparatus: Often confused with the ER. Think of it as the post office. It’s a stack of flattened sacs. Folded pieces of fruit leather or sticks of gum work great here.

Common Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

The biggest mistake is lack of labels. You can build a masterpiece, but if the teacher can't tell your Golgi from your ER, you're losing points. Use toothpicks and small paper flags. Don't just write "Mitochondria." Write "Mitochondria: Site of ATP production." It shows you actually learned the function, not just the name.

💡 You might also like: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Another issue is the "floating organelle" syndrome. In a real cell, things aren't just hovering in a void. They are held in place by the cytoskeleton. If you’re doing a dry model, glue everything down. If you're doing a liquid model (like the gelatin one), make sure you "suspend" the items as the liquid sets so they aren't all sinking to the bottom.

Materials That Actually Work (And Some That Don't)

Stay away from anything that rots. Using a real orange for the nucleus sounds smart until day three when it starts growing mold. That’s a different kind of biology project.

Great materials:

- Polymer clay (stays bright, easy to mold).

- Pipe cleaners (perfect for the cytoskeleton or the ER).

- Beads and buttons (great for ribosomes).

- Recycled plastic (cut-up soda bottles make excellent vacuole walls).

Terrible materials:

📖 Related: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

- Real food (bread, fruit, meat—just don't).

- Wet paint on Styrofoam (certain paints will literally melt the foam).

- Loose glitter (your teacher will hate you forever).

Getting Creative with Your 3D Cell Model Project Plant

If you want to stand out, think about the "state" of the cell. Is it a cell from a leaf? It’ll have tons of chloroplasts. Is it a cell from a root? Zero chloroplasts, because there's no light underground. Mentioning this in your presentation or on your display board shows a level of nuance that most students miss.

You could even do a "Before and After" or a "Healthy vs. Wilting" comparison. A wilting plant cell has a shrunken vacuole and a collapsed cell membrane. It’s a great way to demonstrate osmosis and turgor pressure in a visual way.

Actionable Steps for Your Project

- Pick your "Container" first. This defines the boundaries of your cell wall. A wooden crate, a shoebox, or a deep Tupperware are your best bets.

- Sketch a map. Before you glue anything, draw where the vacuole will go. Everything else has to fit around it.

- Build from the inside out. Start with the large structures like the vacuole and nucleus. Add the smaller organelles (mitochondria, chloroplasts) last.

- The "Texture" Test. Try to use different materials for different parts. If everything is made of clay, it’s hard to tell things apart. Use soft felt for the ER, hard plastic for the vacuole, and rough sandpaper for the cell wall.

- Double-check your key. Make sure your legend matches your labels perfectly. Use a font that is readable from three feet away.

Creating a 3D cell model project plant is fundamentally about demonstrating that you understand how life is organized. When you look at your finished model, you should be able to see a miniature factory where every part has a specific, vital job. If you can explain why the cell wall is thick and why the vacuole is huge, you've already won.