You’re staring at an empty chocolate wrapper or a missing sock, and your heart is pounding. Your dog looks fine right now, but you know that whatever is in their stomach is a ticking time bomb. Panic sets in. You want that thing out. Now.

But wait.

Before you grab the hydrogen peroxide or start googling "how to make my dog vomit," you need to breathe. Seriously. Because if you do this wrong, or if you do it when you shouldn't, you could actually kill your dog. That sounds dramatic, but it’s the reality of veterinary toxicology. Not everything that goes down should come back up.

The "Should I or Shouldn't I" Dilemma

The most important thing to understand is that inducing vomiting—what vets call emesis—is a medical procedure. It is not a DIY home remedy for every situation. There is a very narrow window of time and a very specific list of substances where this is actually helpful.

Usually, you have about two hours. Once that "foreign object" or toxin moves from the stomach into the small intestine, vomiting won't do a lick of good. It's already on its way through the system.

But here is the kicker: Some things are more dangerous coming back up than they were going down. Think about bleach. Or drain cleaner. Or gasoline. These are corrosive or caustic. If they burned the esophagus on the way down, they will dissolve it on the way up. Then there are sharp objects. If your dog swallowed a sewing needle or a large, jagged piece of hard plastic, trying to force it back up through the narrow throat is a recipe for a perforated esophagus. That's a surgical nightmare.

Never, ever induce vomiting if your dog is:

- Already acting lethargic, dizzy, or "drunk."

- Having a seizure.

- A "brachycephalic" breed (think Pugs, Bulldogs, or Frenchies). Their airways are already compromised, and they are at a massive risk for aspiration pneumonia—where they inhale the vomit into their lungs.

- Showing a slow heart rate.

The Only Tool You Should Use: 3% Hydrogen Peroxide

If you’ve called your vet or the Pet Poison Helpline (855-764-7661) and they’ve given you the green light, there is only one substance you should be reaching for.

3% Hydrogen Peroxide.

That’s it. Don't touch the salt. Don't even think about sticking your finger down their throat. And definitely stay away from syrup of ipecac, which is old-school and can actually be toxic to dogs’ hearts.

The way it works is pretty simple. Hydrogen peroxide is a mild irritant to the stomach lining. When it hits the gut, it bubbles up, creates oxygen, and basically tells the stomach "get this out of here."

Getting the Dosage Right

This isn't a "more is better" situation. You need to be precise. The standard rule of thumb used by organizations like the American Kennel Club and most emergency clinics is one teaspoon per five pounds of body weight.

Wait. Don't just pour it.

You should never exceed three tablespoons (9 teaspoons), even if your dog is a 120-pound Great Dane. If you give too much, you risk causing severe hemorrhagic gastritis (bloody stomach inflammation).

Honestly, the hardest part is getting them to swallow it. Most dogs aren't exactly lining up for a shot of bubbly, bitter liquid. A turkey baster or a needleless plastic syringe is your best friend here. Aim for the back of the mouth, near the cheek, and go slow so they don't inhale it.

If nothing happens in 15 minutes? You can usually give one more dose. If they still don't vomit after the second round, stop. Your dog's stomach might be too full, or the peroxide might be expired. Fun fact: if it doesn't fizz when you pour a bit in the sink, it won't work in the dog. It’s just flat water at that point.

When "Coming Up" is a Death Sentence

We talked about corrosives, but there's a whole category of "No-Go" items that catch people off guard. Hydrocarbons are the big ones. This includes motor oil, gasoline, and kerosene. These liquids are "slippery" and very easy to inhale. If your dog gets even a tiny bit of gasoline in their lungs while vomiting, they can develop fatal aspiration pneumonia within hours.

Then there’s the "Dough Rule." If your dog ate raw bread dough with yeast, do not make them vomit unless a vet is standing right there. The warm environment of the stomach makes the dough expand rapidly. If you try to force that giant, sticky mass back up the esophagus, it can get stuck and cause a total airway obstruction.

Real World Examples: The Good, The Bad, and The Chocolate

Let’s look at a common scenario. It’s Christmas. Your lab, Barnaby, eats a bag of dark chocolate chips. Dark chocolate contains high levels of theobromine and caffeine. This is a classic "Yes, make them vomit" situation. You caught him in the act, he’s alert, and the toxin hasn't been absorbed yet.

Contrast that with a dog that ate a bunch of grapes four hours ago. By now, the toxins that cause kidney failure in grapes are likely already being processed. Making the dog vomit now just stresses their body and causes dehydration without actually removing the danger.

Or consider the "Sock Eater." If a Golden Retriever swallows a thin dress sock, vets often suggest inducing vomiting because it's soft and likely to slide back up. But if that same dog swallows a heavy, thick hiking sock? That might be too bulky to clear the cardiac sphincter (the opening into the stomach). Trying to force it up could cause it to lodge in the esophagus, turning a "wait and see" or a simple endoscopy into a major chest surgery.

What to do After the Puking Stops

Once the deed is done, you aren't out of the woods. First, inspect the vomit. It’s gross, but you need to know if the "offending object" actually came out. If your dog ate a sugar-free gum pack containing Xylitol and you don't see any gum in the puke, the poison is still in there.

✨ Don't miss: Thirty pound weight loss before and after: What actually happens to your body (and brain)

Afterward, your dog’s stomach is going to be incredibly raw. Think about how you feel after a stomach flu. Don't offer a giant bowl of kibble. Most vets recommend withholding food for several hours and then starting with something bland—boiled chicken and white rice is the gold standard.

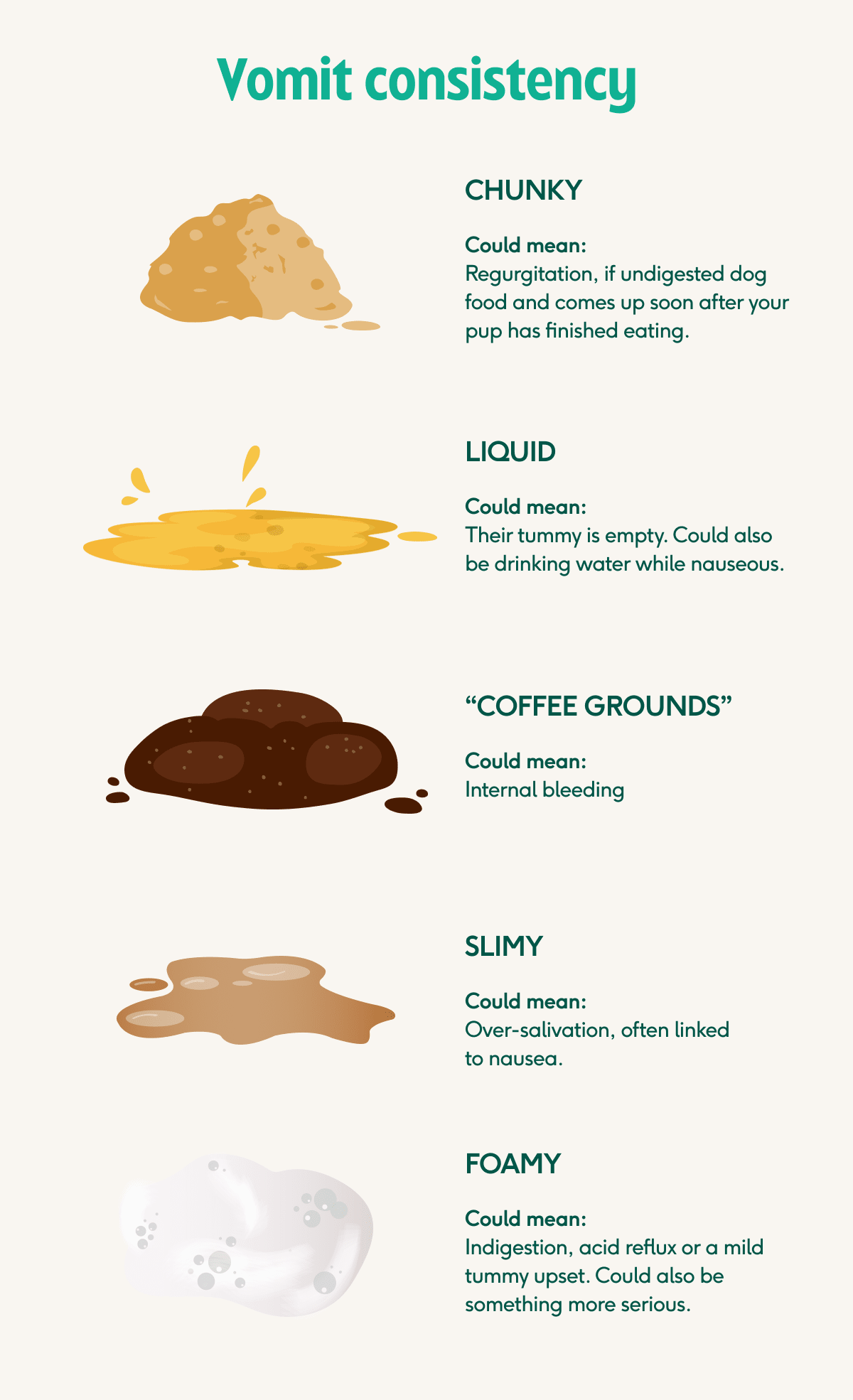

Also, watch for the "bloody froth." A little bit of pink tinged foam is common because peroxide is an irritant. But if you see bright red blood or coffee-ground looking material, that’s an emergency. That means the stomach lining is damaged.

The Professional Alternative: Apomorphine

If you can get to an ER vet, they won't use peroxide. They use a drug called Apomorphine. It’s fascinating stuff. They usually put a tiny tablet in the dog's conjunctival sac (the corner of the eye). It absorbs into the bloodstream, hits the vomiting center in the brain, and—boom—the dog vomits almost instantly.

The beauty of this is that once the stomach is empty, the vet can wash the eye out, which stops the drug's effect. They can also give an anti-nausea injection (like Maropitant) immediately after so the dog doesn't keep retching for hours. It’s much more controlled and way less irritating than the home method.

Actionable Steps for the "Right Now"

If you are reading this because your dog just ate something they shouldn't have, follow these steps in order:

- Identify the Toxin: Was it a chemical, a food, or an object? If it was a cleaning product or a human medication, grab the container.

- Check the Time: Did this happen within the last 60 to 90 minutes?

- Assess the Dog: Is your dog standing, breathing normally, and acting like themselves?

- Call the Experts: Contact your vet or a poison control center. They have databases that tell them exactly how many milligrams of a substance are toxic based on your dog's weight.

- Check Your Supplies: Find 3% Hydrogen Peroxide. Ensure it is not expired and still bubbles.

- Measure and Administer: Use 1 teaspoon per 5 lbs of body weight. Use a syringe or turkey baster.

- Walk Them: After giving the peroxide, gently walk your dog around. Moving their body helps "mix" the peroxide in the stomach, which triggers the reaction faster.

- The Collection: Have a plastic bag or paper towels ready. You need to see what came out.

- Follow Up: Even if they vomited the object, a trip to the vet is often still necessary to check for lingering toxins or to get a stomach-coating medication like Sucralfate.

Making your dog vomit is a high-stakes move. It feels like the "handy" thing to do, but it’s a tool that requires a lot of respect. Keep that bottle of peroxide in your first aid kit, but keep your vet's number right next to it. Most of the time, the phone call is more important than the peroxide.

Keep a close eye on your dog's hydration in the six hours following emesis. Providing small amounts of water or unflavored Pedialyte can help stabilize them after the physical stress of vomiting. If your dog remains lethargic or refuses to drink after four hours, an underlying issue or secondary reaction to the toxin may be occurring, requiring immediate professional intervention. Always err on the side of caution and prioritize a clinical exam if the situation feels "off" in any way.