You’ve seen the hype. Hydrogen is supposedly the "fuel of the future," the clean energy holy grail that will save us from carbon emissions. But if you try to look up how to make a hydrogen fuel cell, you usually run into two extremes: overly simplistic science fair projects that barely light an LED, or dense academic papers that require a PhD in electrochemistry just to understand the introduction.

It’s frustrating.

The reality is that building a functional Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cell—the kind used in actual vehicles—is a delicate balancing act of chemistry and precision engineering. You aren't just slapping some wires together. You are creating a controlled environment where a chemical reaction generates electricity, heat, and water. It’s basically a battery that never runs out, as long as you keep feeding it.

The Science Most People Skip

Before you grab your tools, you have to understand what’s actually happening inside the stack. Most people think a fuel cell "burns" hydrogen. It doesn't. If you burn hydrogen, you get a localized release of thermal energy. In a fuel cell, we are stripping electrons away.

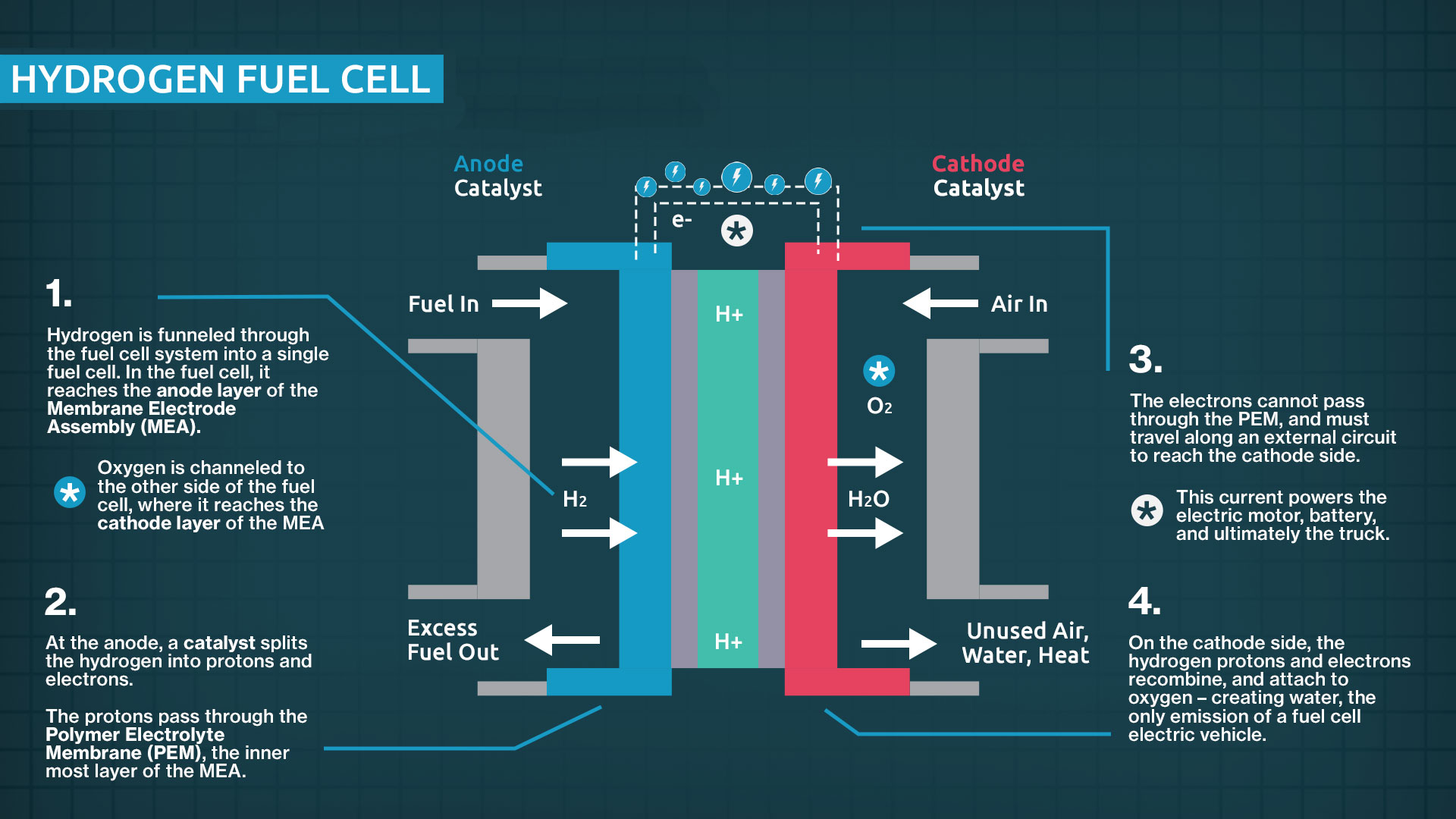

At the heart of the device is the Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA). This is the "brain." It consists of a specialized polymer membrane—usually Nafion, developed by DuPont—sandwiched between two catalyst layers. These layers are typically coated with platinum. Why platinum? Because it’s one of the few materials efficient enough to catalyze the dissociation of hydrogen molecules at relatively low temperatures.

🔗 Read more: Why an Aux Jack Bluetooth Adapter Is Still Your Best Budget Audio Hack

When hydrogen gas ($H_2$) hits the anode side, the platinum catalyst forces it to split into protons and electrons. This is where the magic happens. The Nafion membrane is "proton-conductive" but an electrical insulator. It allows the protons to pass through to the other side, but it blocks the electrons. Those stranded electrons are forced to travel through an external circuit to reach the cathode, and that flow of electrons is exactly what we call electricity.

On the cathode side, oxygen from the air meets up with those returning electrons and the protons that pushed through the membrane. They recombine. The only byproduct? $H_2O$. Pure water.

What You’ll Actually Need

Don't expect to find everything at a local hardware store. To build a legitimate PEM fuel cell, you need specific materials.

- Nafion Membrane: You can buy sheets of Nafion 117 or 212 online. It’s expensive. Handle it with gloves; oils from your skin will ruin the proton conductivity.

- Catalyst-Coated Carbon Paper: This acts as the Gas Diffusion Layer (GDL). You need carbon paper or cloth coated with a platinum catalyst (usually 0.5 mg/cm² loading).

- Bipolar Plates: These are the "walls" of your cell. They need to be conductive and have flow channels etched into them to distribute the gas. Graphite is the gold standard here because it doesn't corrode, but it’s brittle.

- Gaskets: Silicon or Viton work best to prevent gas leaks.

- End Plates: Thick acrylic or aluminum plates to bolt the whole thing together.

The Step-by-Step Build

First, you have to prep the MEA. If you didn't buy a pre-made membrane-electrode assembly, you’ll have to "sandwich" the Nafion between two pieces of catalyst-coated carbon paper. This usually requires a hot press. Professional labs like those at NREL (National Renewable Energy Laboratory) use precise temperatures around 130°C to bond these layers without melting the polymer.

Next comes the flow plates. You need to create a "serpentine" pattern. Imagine a long, winding river carved into the surface of your graphite or metal plate. This ensures that the hydrogen and oxygen (or ambient air) spend as much time as possible in contact with the catalyst. If the gas just shoots straight through, the reaction efficiency drops to near zero.

When you assemble the stack, alignment is everything. If your gaskets are even a millimeter off, you’ll have hydrogen leaking into the oxygen side. In the best-case scenario, the cell won't work. In the worst-case scenario, you’ve created a tiny, pressurized bomb.

Tightening the bolts is the final, crucial step. You need even pressure across the entire surface. If one corner is tighter than the rest, you’ll crack your graphite plates or create "hot spots" where the membrane dries out and fails. Most experts recommend using a torque wrench to ensure every bolt is tightened to the exact same specification.

The Moisture Problem

Here is a detail that almost every DIY guide misses: Nafion must be hydrated. If the membrane dries out, it stops conducting protons. It becomes a piece of plastic.

In professional systems, like the ones used in the Toyota Mirai, they use sophisticated humidifiers to moisten the incoming hydrogen. For a home-built setup, you might need to bubble your hydrogen through a container of deionized water before it enters the cell. However, you can’t have too much water. If the water builds up in the flow channels, it "floods" the cell, blocking the gas from reaching the catalyst. This "water management" is arguably the hardest part of fuel cell engineering.

Why This is Harder Than It Looks

You might spend $500 on materials and only generate 1 or 2 watts of power. It's humbling.

The limitations are real. Platinum is insanely expensive, which is why researchers are desperately looking for non-precious metal catalysts (like iron or nitrogen-doped carbon). Then there’s the hydrogen itself. Storing it is a nightmare because it's the smallest molecule in the universe; it leaks through almost anything.

Moreover, the purity of your gases matters. If your hydrogen has even a tiny amount of carbon monoxide (CO) in it, it will "poison" the platinum catalyst. The CO sticks to the platinum sites more aggressively than the hydrogen does, effectively shutting down the reaction.

Real-World Applications and Context

We aren't just talking about science experiments. Companies like Ballard Power Systems and Plug Power are already deploying these at scale for forklifts and heavy-duty transit. Why? Because batteries are heavy. For a long-haul truck, carrying enough batteries to go 500 miles would eat up half the cargo capacity. Hydrogen offers a much higher energy density by weight.

However, the "green-ness" of your fuel cell depends entirely on where the hydrogen comes from. Currently, about 95% of hydrogen is produced via "steam methane reforming" (SMR), which uses natural gas and releases $CO_2$. To make it truly clean, you need to use an electrolyzer powered by solar or wind to split water into hydrogen and oxygen. Making the fuel cell is just one half of the equation; sourcing the fuel is the other.

Actionable Next Steps for Builders

If you are serious about building one, don't start by buying raw platinum powder.

✨ Don't miss: TikTok Banned: What Most People Get Wrong About the 2026 Deadlines

- Buy a Pre-made MEA: Start with a manufactured Membrane Electrode Assembly. It eliminates the hardest variable (the catalyst bonding) and lets you focus on the mechanical assembly of the plates.

- Use Graphite Plates: Avoid metal for your first build. Aluminum or steel will corrode almost instantly in the acidic environment of a PEM cell unless they are coated with expensive gold or titanium nitrides.

- Check for Leaks First: Before introducing hydrogen, pressure test your cell with nitrogen or even plain air. Submerge it in water (without the electronics connected) and look for bubbles.

- Invest in a Purge Valve: You need a way to "flush" the anode side occasionally to get rid of accumulated water and nitrogen that crosses over from the air side.

- Safety First: Always use a hydrogen sensor in your workspace. Hydrogen is odorless, colorless, and highly flammable over a wide range of concentrations in air.

Building a hydrogen fuel cell is a masterclass in multidisciplinary engineering. It forces you to learn about fluid dynamics, materials science, and electrical load balancing all at once. Even a cell that only generates enough power to spin a small fan is a massive technical achievement. Focus on the seal integrity and membrane hydration first, and the power output will follow.