You’re standing over a pot of braising short ribs or maybe a delicate berry coulis. The recipe says "cover with a cartouche." If you aren't a professional chef or a French culinary school grad, you might just reach for the heavy pot lid and call it a day. Don't do that. Honestly, a lid is often the enemy of a perfect reduction.

A cartouche is basically just a circle of greaseproof paper. It sits directly on the surface of your food. It’s a false lid. Sounds simple, right? It is, but the physics behind why it works is what separates a watery, gray stew from a glossy, rich masterpiece.

Most people think lids are about trapping heat. They are. But lids also trap every drop of steam, which then hits the cold metal, turns back into water, and drips right back into your sauce. This dilutes your flavors. A cartouche, however, allows a tiny bit of evaporation while keeping the top of the food moist. It prevents that gross "skin" from forming on custards or sauces. It's the secret to why restaurant sauces look like velvet.

Why You Actually Need to Know How to Make a Cartouche

If you’ve ever simmered a tomato sauce for three hours only for it to stay thin, your lid was likely the culprit. Or maybe you’ve poached pears and the tops turned brown because they were poking out of the liquid. That’s where the cartouche saves your life. It keeps the ingredients submerged. It creates a localized steaming environment.

Professional kitchens use parchment paper because it’s cheap and heat-resistant. You don't need fancy tools. Just a roll of parchment and some scissors. If you use wax paper, you're going to have a bad time—it’ll melt. Stick to parchment.

The Folding Method: A Step-by-Step That Actually Works

Forget trying to trace a circle using a plate. That’s amateur hour and it’s messy. The "chef way" is a bit like making a paper snowflake in third grade.

📖 Related: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

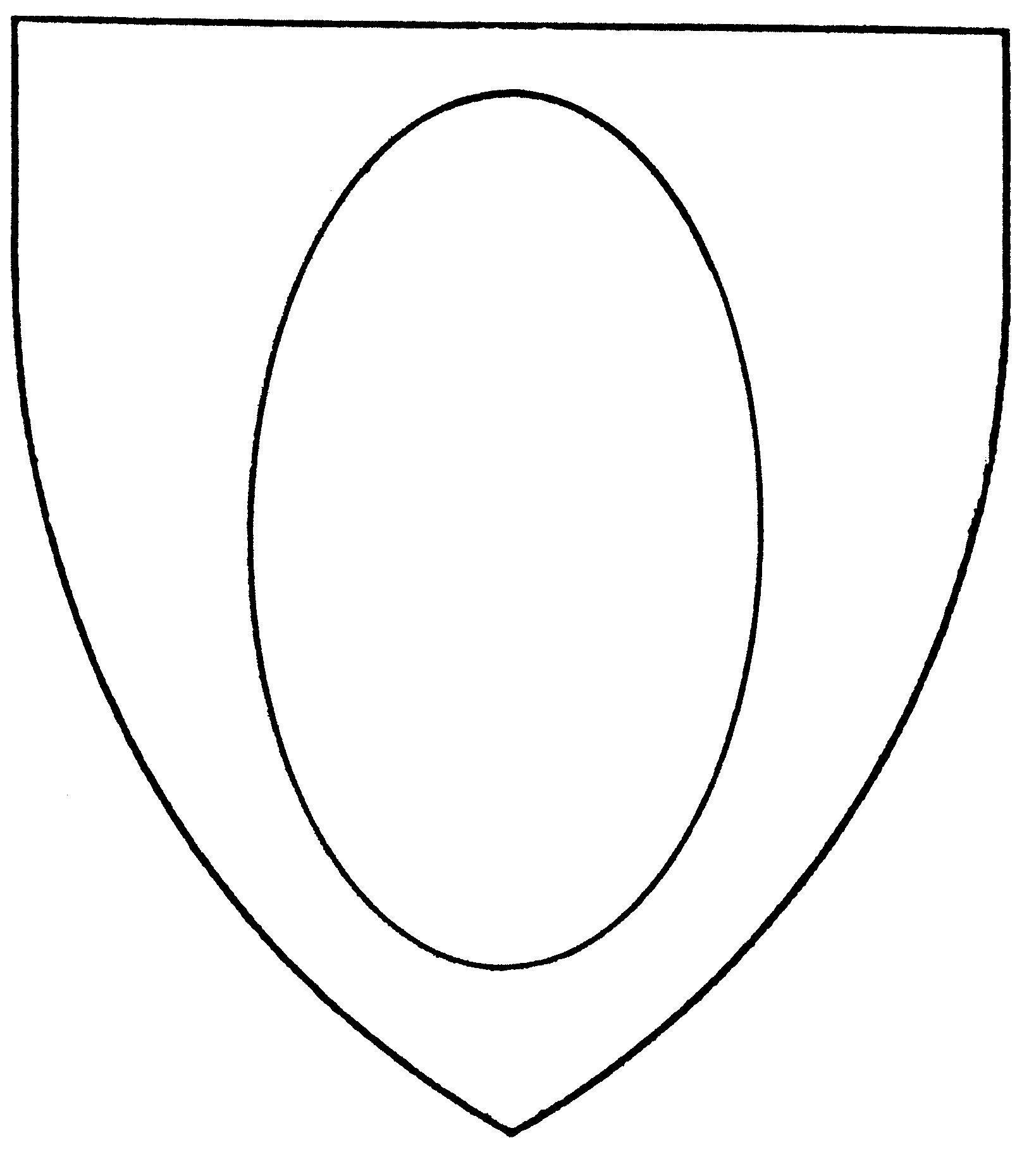

First, tear off a square of parchment paper. Make sure the square is slightly larger than the diameter of your pan. If you're using a standard 10-inch skillet, a 12-inch square is perfect. Fold it in half to make a rectangle. Fold it in half again to make a smaller square. Now, fold it diagonally to create a triangle. Keep folding that triangle over itself, pivoting from the center point, until you have a thin, multi-layered wedge. It should look like a very narrow slice of pizza.

Now, hold the tip of the wedge (the center of the paper) over the center of your pot. Take your scissors and snip the wide end of the paper right where it hits the edge of the pot.

Pro tip: Snip the very tip off too. Just a tiny bit. This creates a small hole in the center. When you unfold the paper, you’ll have a near-perfect circle with a vent in the middle. This vent is crucial. It lets the excess steam escape so your sauce thickens while the surface stays basted.

Common Mistakes People Make with Paper Lids

I’ve seen people try to use aluminum foil for this. It sort of works, but foil doesn't breathe. It also reacts with acidic foods like tomatoes or wine. You’ll end up with a metallic-tasting braise. Not great.

Another big mistake is not pushing the paper down. When you place the cartouche on the food, you need to gently press it so it makes contact with the liquid. You want to see the paper get a little "wet" from the fat or moisture. This creates the seal. If it’s just hovering above the food, it’s just a paper lid, not a cartouche.

👉 See also: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

What about heat? Parchment is generally safe up to 425°F or 450°F. If you’re braising in the oven, you’re usually at 300°F or 325°F. You're totally safe. Just make sure the paper isn't hanging over the edges of the pot if you're cooking over a gas flame. Fire is bad for paper. Obviously.

When Should You Use This Technique?

You won't use this for boiling pasta. That would be weird. Use it for:

- Braising Meat: It keeps the exposed part of the meat from drying out while the bottom half simmers.

- Poaching Fruit: Keeps pears or peaches fully submerged in the spiced wine or syrup.

- Reducing Sauces: Allows slow evaporation while preventing a skin from forming.

- Confit: If you're making duck or garlic confit, a cartouche ensures everything stays under the oil.

- Pastry Creams: Pressing a cartouche (or plastic wrap, if it's cold) directly onto a hot custard keeps it smooth.

The Science of the "False Lid"

Escoffier and the old-school French brigade system popularized the cartouche because they obsessed over "fond"—the browned bits of flavor. When you use a heavy lid, you get "rain" inside the pot. This rain washes the flavorful browned bits off the sides of the pot and back into the liquid, but in a way that’s too diluted.

With a cartouche, the evaporation is controlled. The liquid level drops slowly, and the flavors concentrate. Because the paper is permeable, it doesn't create a pressurized environment. It’s gentle. Cooking is often just the management of moisture, and this is the most precise tool for that job.

Troubleshooting Your Cartouche

Sometimes the paper curls up. It’s annoying. If that happens, just wet the paper slightly under the tap before you put it on the food. The weight of the water will help it stay flat and stick to the surface.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

If you find your sauce is still too thin after an hour, your center hole might be too small. Just take the paper off, fold it back up, and snip a slightly larger bit off the tip. Or, just move the paper slightly to one side. It’s flexible. Unlike a heavy Le Creuset lid, you can manipulate paper.

Also, don't throw the paper away immediately if you're resting the meat. Keep it on there while the pot sits off the heat. It’ll keep the heat in without overcooking the dish, and it prevents the top layer from oxidizing and turning a weird color.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Meal

Next time you make a stew or a thick soup, try this.

- Get the right paper. Look for "unbleached parchment" if you want to be eco-friendly, but any kitchen parchment works.

- Size it up. Don't eyeball it. Use the folding method described above to get a circle that actually fits your specific pan.

- The Snip. Don't forget the center vent hole. It's the difference between a braise and a boil.

- Watch the edges. If you're cooking on a gas range, trim any excess paper that hangs over the side of the pot to avoid a kitchen fire.

- Press and Seal. Gently tap the paper onto the surface of the food until it's slightly saturated with the cooking liquid.

Mastering how to make a cartouche is one of those tiny skills that shifts your cooking from "home cook" to "someone who knows what they're doing." It costs almost nothing and changes the texture of your food immediately.