You’re staring at a coordinate plane. There’s a triangle—let’s call it $\triangle ABC$—and a lonely-looking arrow pointing off into space. Your task is to draw the translation of the figure along the translation vector, and honestly, it feels like one of those tasks that should be simpler than it actually is. It’s just sliding, right? But then you start counting grid squares, lose your place, and suddenly your "translated" triangle looks like it’s been through a blender.

Geometry isn't just about shapes. It’s about movement. When we talk about a translation, we are talking about a rigid transformation. The shape doesn't grow. It doesn't shrink. It doesn't flip or spin like a top. It just... shifts. Think of it like a chess piece moving across the board; the piece stays the same, but its address changes.

The Vector is Your Roadmap

Before you even touch your pencil to the paper to draw the translation of the figure along the translation vector, you have to understand what that vector is actually telling you. In mathematics, a vector is basically a set of instructions. It has two parts: magnitude and direction.

Usually, you'll see a vector written in component form, like $\langle h, k \rangle$. The first number, $h$, is your horizontal command. If it's positive, you move right. If it's negative, you head left. The second number, $k$, is your vertical command. Up for positive, down for negative. It's a GPS coordinate for every single point on your figure. If your vector is $\langle 5, -2 \rangle$, you aren't just moving the "shape." You are moving every individual microscopic point five units to the right and two units down.

The Step-by-Step Reality of Moving Shapes

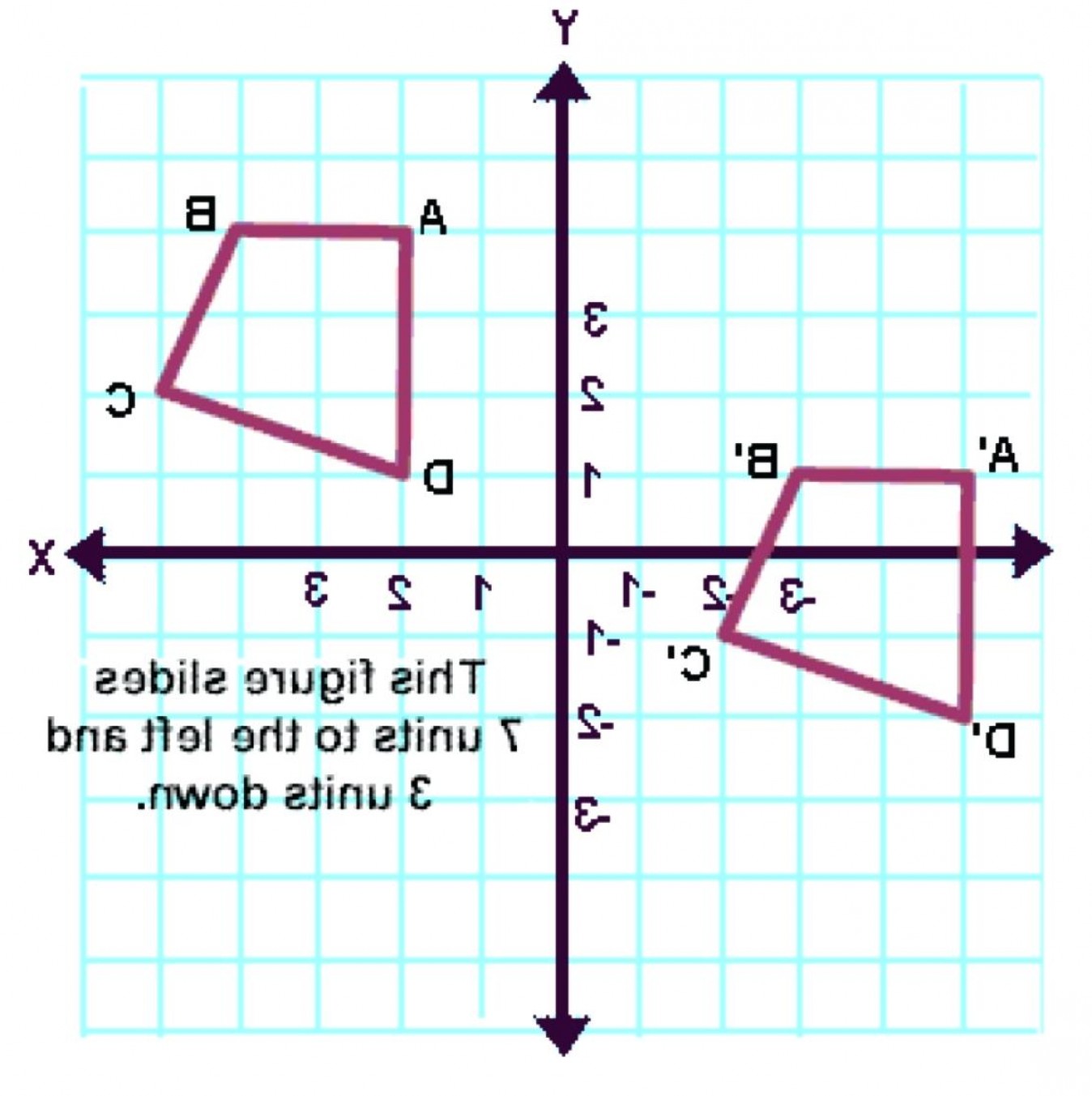

Let's get practical. You have a quadrilateral on a Cartesian plane. The vertices are at specific coordinates. To successfully draw the translation of the figure along the translation vector, you should ignore the lines connecting the points for a second. Just look at the corners.

✨ Don't miss: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

- Pick a vertex. Let’s call it Point $A$.

- Apply the vector components to Point $A$’s coordinates. If $A$ is at $(1, 2)$ and your vector is $\langle 3, 4 \rangle$, your new point $A'$ (we call that A-prime) will be at $(1+3, 2+4)$, which is $(4, 6)$.

- Repeat this for every single vertex. Point $B$ becomes $B'$, $C$ becomes $C'$, and so on.

- Once you have all your "prime" points plotted, grab a straightedge. Connect them.

If the new shape looks different from the old one—if it’s skinnier, fatter, or tilted—you messed up the math on one of the points. It happens. Usually, it's a sign error. You subtracted when you should have added because a negative sign was lurking in the vector instructions.

Why Does This Actually Matter?

You might think this is just busywork for a 10th-grade geometry quiz. It isn't. This is the fundamental logic behind computer graphics. When you’re playing a video game and your character walks across the screen, the game’s engine is constantly calculating translations. The character model (the figure) is being moved along a vector determined by your joystick input.

In engineering and architecture, translation is used in CAD (Computer-Aided Design) software to replicate components. If you're designing a bridge and you need ten identical bolts spaced evenly apart, you don't redraw the bolt ten times. You define the first one and then translate it along a vector repeatedly. It’s about efficiency and precision.

Common Pitfalls: The "Visual Lean"

One of the biggest mistakes people make when they try to draw the translation of the figure along the translation vector is trusting their eyes too much. You think you can see where the shape should go. You "eye it."

🔗 Read more: The iPhone 5c Release Date: What Most People Get Wrong

Don't do that.

The human brain is surprisingly bad at maintaining perfect spatial ratios without help. If you're off by just half a grid square on one vertex, the entire geometric integrity of the figure is compromised. This is technically called a "non-isometric" result, though in a classroom, your teacher will just call it "wrong."

Another weird quirk? Forgetting that the vector itself has a starting point and an ending point. The vector isn't a line you draw on the shape; it's a description of the distance between the "Pre-image" (the original) and the "Image" (the new one).

Mapping it Out Mathematically

If you want to be fancy—or if you're working on a problem that doesn't give you a grid—you use the translation function. It looks like this: $T(x, y) = (x + h, y + k)$.

💡 You might also like: Doom on the MacBook Touch Bar: Why We Keep Porting 90s Games to Tiny OLED Strips

Imagine your figure is a circle. You can't really "move the corners" of a circle because it doesn't have any. In that case, you translate the center point. If the center of your circle moves from $(0,0)$ to $(5,5)$ along the vector $\langle 5, 5 \rangle$, the radius stays exactly the same. You just draw the same circle at the new center.

Real-World Nuance: Vectors in Non-Euclidean Spaces

Now, if we really want to get into the weeds, translations aren't always on a flat piece of paper. In specialized fields like geodesy (the study of the Earth's shape) or General Relativity, "sliding" a figure along a vector is way more complicated because the surface is curved. This is called parallel transport. If you move a vector along a sphere, it might end up pointing in a different direction than it started, even if you never "turned" it.

But for most of us, we’re sticking to the flat Euclidean plane. It’s safer there.

Actionable Tips for Perfect Translations

If you're working on a project or an assignment right now, here is how you ensure 100% accuracy:

- Use Patty Paper: This is a classic trick. Trace your original figure and the vector on a piece of transparent parchment paper. Slide the paper along the vector line. Mark the new points by poking through the paper with your pencil.

- Color Code: Use a blue pen for the pre-image and a red pen for the image. It helps your brain distinguish between "where I was" and "where I am."

- Double-Check the Vector Direction: Check if the arrow head is on the right end. A vector from $P$ to $Q$ is not the same as a vector from $Q$ to $P$. You’ll end up in the exact opposite quadrant.

- Verify Slopes: If you're translating a line segment, the slope of the original segment and the slope of the translated segment must be identical. They are parallel lines. If they aren't parallel, one of your points is a "rogue" point.

To get started, take a simple square on a piece of graph paper. Define a vector—let's say 4 units right and 3 units up. Physically count out the movement for each of the four corners. Mark them as $A', B', C',$ and $D'$. Connect the dots. You have successfully mastered the most fundamental movement in the geometric world.

Next time you see a character move on a screen or a robotic arm shift a part in a factory, you'll know exactly what's happening behind the scenes: it's just a figure following a vector.