You can’t really see an earthquake. You see what it does. That’s the tricky part when you sit down and figure out how to draw an earthquake—you aren't drawing a "thing," you're drawing a massive release of energy. Most people make the mistake of just drawing a zigzag line on the ground and calling it a day. But if you want it to look real, to feel like the ground is actually screaming, you’ve got to think like a seismologist and an artist at the same time. It’s about movement.

It’s messy.

Think about the Richter scale. Or better yet, look at a seismograph readout. It’s a chaotic dance of ink. When the tectonic plates decide they’ve had enough of each other's company, the result isn't a neat, clean crack. It’s a violent, multi-directional shattering of everything we consider "solid." To capture that, your hand needs to be loose. If you’re too precious with your lines, it’s going to look like a cracked sidewalk, not a natural disaster.

The Seismology of the Sketch: Understanding Fault Lines

Before you even touch a pencil to paper, you need to understand what’s actually happening under the dirt. Geologists like those at the United States Geological Survey (USGS) talk about different types of faults. You’ve got your strike-slip faults, where things slide past each other horizontally—think the San Andreas. Then you’ve got normal and reverse faults where the ground actually moves up or down.

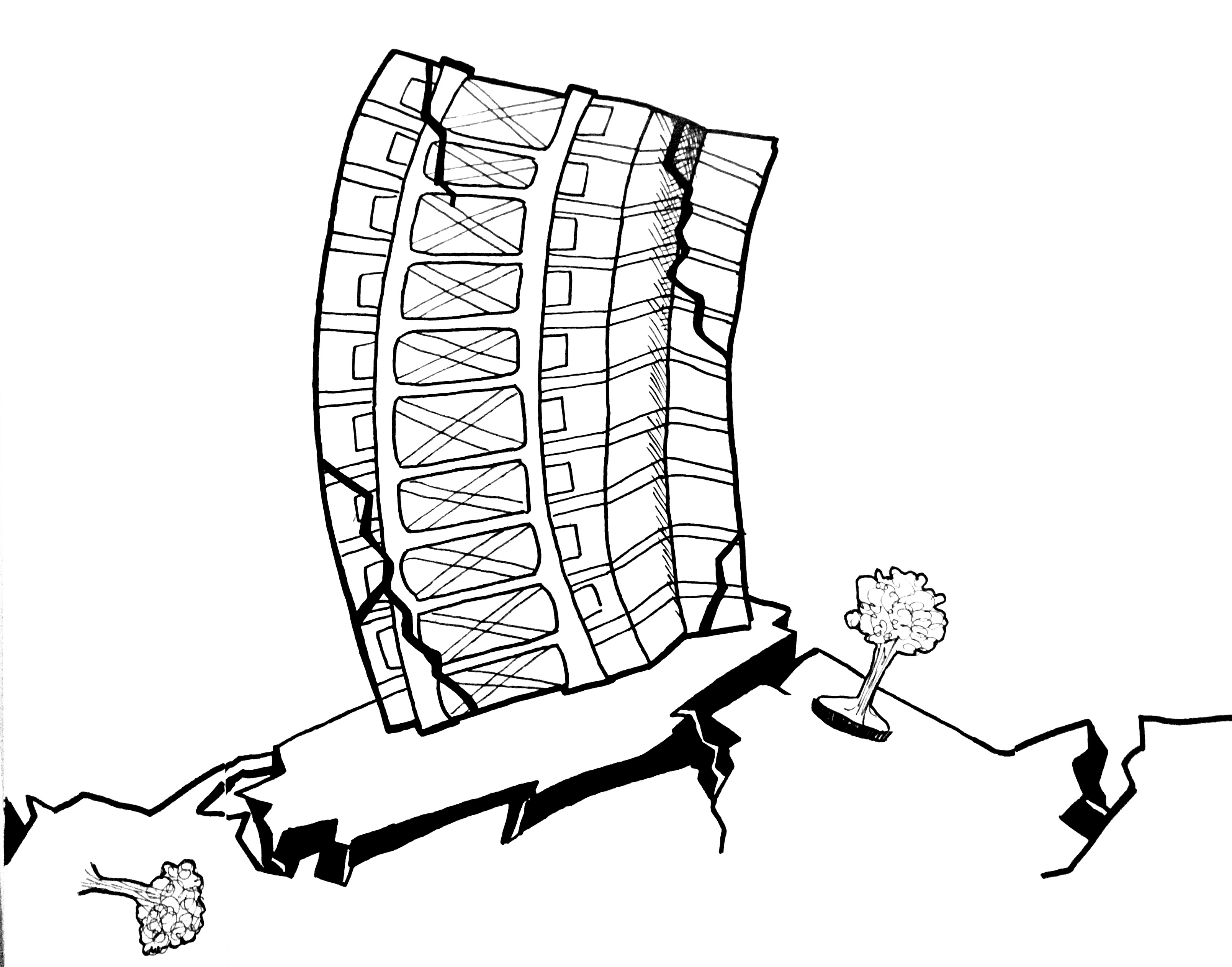

When you’re learning how to draw an earthquake, decide which one you're tackling. If the ground is pulling apart, you’ll see jagged cliffs (called scarps) where one side of the earth has literally dropped. This adds immediate depth to a drawing. Instead of just a line, you have a 3D ledge.

I’ve spent hours looking at photos from the 1906 San Francisco quake or the more recent 2023 Turkey-Syria events. The ground doesn't just split; it heaves. It ripples. Sometimes it liquefies. Soil liquefaction is this wild phenomenon where saturated soil loses its strength and acts like a liquid. In a drawing, this looks like buildings leaning at impossible, drunken angles without actually being broken in half. It’s eerie. It’s effective.

Techniques for Shaky Lines and Kinetic Impact

Stop trying to draw straight lines. Seriously.

💡 You might also like: 5 feet 8 inches in cm: Why This Specific Height Tricky to Calculate Exactly

To get that "shaking" effect, use a technique called stippling combined with scumbling. You want the edges of objects—buildings, trees, cars—to look blurred, as if the camera (or the viewer’s eye) can't focus because everything is vibrating at 40 cycles per second.

- Use a softer lead pencil, like a 4B or 6B. Hard pencils are for architects. Soft pencils are for chaos.

- Hold the pencil further back. Don't choke up on the nib. This gives you less control, which is exactly what you want here.

- Draw the "ghost" of the object first. Draw a house, then draw a slightly shifted, lighter version of that house right next to it. This creates a visual vibration.

Conveying the Sound Through Visuals

You can’t hear a drawing, obviously. But you can make a drawing look loud. In the world of comic book art, this is done with "impact lines" or "speed lines." But in a realistic SEO-friendly piece of art, you do it with debris.

Dust is your best friend. When the earth moves, things grind together. Grinding rock creates dust clouds. By adding plumes of fine silt and grit rising from the cracks in the pavement, you’re signaling to the brain that there is friction. High friction equals high energy.

Composition: Where Does the Eye Go?

A common mistake in how to draw an earthquake is centering the crack. It’s boring. It’s too symmetrical.

Try using the Rule of Thirds. Put your primary "fissure" or the most damaged building on one of the vertical grid lines. This creates a sense of imbalance. Earthquakes are the definition of imbalance. You want the viewer to feel slightly uncomfortable looking at the piece.

Perspective matters here more than almost anywhere else. A "worm’s eye view"—looking up from the ground—makes the falling debris look massive and terrifying. If you draw from a "bird’s eye view," you focus more on the topographical changes, the way a road now looks like a broken snake.

📖 Related: 2025 Year of What: Why the Wood Snake and Quantum Science are Running the Show

Material Matters: Asphalt vs. Earth

Drawing a crack in a road is different from drawing a crack in a field. Asphalt is brittle. It snaps. It creates sharp, triangular shards. Think of it like a broken cookie.

Dirt, however, is organic. It clumps. It has roots sticking out. When you're detailing the interior of a fissure, don't just leave it black. Add layers. Show the different strata of the soil. Maybe there's a broken pipe or a twisted rebar sticking out. These small, factual details—the "anatomy" of the infrastructure—are what make a drawing go from a "doodle" to a professional illustration.

Lighting the Chaos

What’s the light source? Usually, in a disaster, power lines are down. You might have the harsh, orange glow of a gas fire, or just the flat, oppressive gray of a dust-filled sky.

If you want to be dramatic, use Chiaroscuro. This is the Italian term for strong contrasts between light and dark. Imagine the deep, pitch-black shadows inside the earth's new opening, contrasted with the bright, sharp sunlight hitting the jagged edge of the broken concrete. This contrast creates "pop." It makes the hole look deep. It makes the danger feel real.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- The "Lightning Bolt" Trap: Don't draw the crack like a cartoon lightning bolt. Real earth-cracks follow the path of least resistance. They curve, they stop, they branch out into tiny "micro-cracks."

- Static Buildings: If the ground is moving, the buildings shouldn't be vertical. Even if they aren't falling, they should be tilted.

- Clean Clothes: If you’re drawing people in the scene, they should be covered in the same dust you’ve added to the air.

Actionable Steps for Your First Earthquake Sketch

Ready to actually put graphite to paper? Don't start with a masterpiece. Start with a study of stress.

First, grab a piece of charcoal. It’s the best medium for this because it’s smudgeable and dark. Draw a straight line representing the horizon. Now, "break" it. Smudge the left side upward and the right side downward.

👉 See also: 10am PST to Arizona Time: Why It’s Usually the Same and Why It’s Not

Next, focus on the "ejecta." These are the bits of stone and dirt that get tossed into the air. Use quick, flicking motions with your wrist to create these. They should be concentrated near the areas of highest movement.

Finally, add the human element. You don't need a person; maybe just a dropped briefcase or a bicycle lying on its side. These "still life" elements provide a scale for the massive power of the quake.

To really master how to draw an earthquake, you have to stop thinking about the lines and start thinking about the force. The earth isn't just a surface; it's a living, moving, occasionally violent entity. Your job is to capture the moment it loses its temper.

Go find a photo of the Loma Prieta damage or the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Look at the way the wood splintered. Look at how the bricks didn't just fall; they exploded outward. Copy those textures.

Start with the heavy shadows in the depths of the fault. Build the debris layers on top of that. Use a kneaded eraser to "pull" light out of the dust clouds. Keep your movements fast. If you're bored while drawing it, the viewer will be bored looking at it. Keep the energy high, keep the lines messy, and let the chaos take over the page.

Next Steps for Success:

- Study Seismographs: Print out a real seismograph reading and try to mimic the "spiky" rhythm of the lines to practice hand-eye coordination for shaky textures.

- Texture Practice: Spend fifteen minutes drawing only "broken concrete" textures to understand how light hits jagged, non-uniform edges.

- Perspective Shift: Re-draw the same scene from three different heights to see which one conveys the most "weight" and danger.