Drawing a Katana is deceptive. It looks simple—just a curved blade, right? Wrong. Most people end up with something that looks like a bent piece of rebar or a flimsy kitchen knife. If you want to know how to draw a samurai sword that actually carries the weight and "soul" of a Japanese masterpiece, you have to understand the geometry of the Sori (the curve) and the way light plays off the Hamon.

The Katana is a weapon of precision. It isn't just a sword; it’s an engineering marvel from the Muromachi and Edo periods. Honestly, if your lines are too straight, it’s not a Katana. If the curve is a perfect semicircle, it’s not a Katana either. It's a subtle, tapering arc that demands a specific hand-eye coordination to capture on paper.

The geometry of the blade and the curve

Let’s talk about the Sori. This is the curvature of the blade. Most beginners draw a big, sweeping "C" shape. Don't do that. A real Katana has a curve that is often more pronounced near the hilt (known as Koshi-zori) or centered (Chu-zori).

You’ve gotta start with a light gesture line. Use a 2H pencil if you’re working traditionally. Draw one long, elegant curve. This is your spine. Then, you need to parallel that line, but here’s the kicker: the blade tapers. It is wider at the Muchi (near the handle) and narrower at the Kissaki (the tip). If you keep the width uniform, the sword will look like a toy.

The thickness of a real blade is usually only about 7-8mm at the base. On paper, this translates to a very slender profile.

Why the Kissaki makes or breaks the drawing

The tip, or Kissaki, is where most artists fail. It’s not just a point. It’s a complex intersection of planes. There is a visible line called the Yokote—it’s a vertical line that separates the tip from the rest of the blade.

Think of it like a chisel.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

When you’re figuring out how to draw a samurai sword, spend ten minutes just practicing the Yokote. If you miss this line, the sword loses its structural integrity. It just looks like a flat piece of metal. You want it to look like it could actually slice through a tatami mat.

Real blades have a Mune (the back edge). This isn't just a line; it’s often triangular or "roof-shaped." If you’re drawing at an angle, you need to show two lines for the back of the sword to give it three-dimensional volume.

Mastering the Tsukamaki (The Handle Wrap)

The handle, or Tsuka, is a nightmare for the impatient. It’s wrapped in silk or cotton cord called Ito over rayskin (Samegawa).

Don't just draw crisscross lines. That looks like a garden fence.

The wrap is a series of overlapping diamonds. Each fold of the cord goes over and then under the next. This creates a rhythmic, textured pattern. To make it look authentic, draw the diamonds first, then add the slight "over-under" overlap at the corners. Also, the handle isn't a perfect cylinder. It’s slightly waisted—a bit thinner in the middle than at the ends. This is called the Rikko shape. It helps the samurai keep a grip when their hands are sweaty or, well, bloody.

The Tsuba and the subtle details

The guard, or Tsuba, is where you can get creative. While some were plain iron circles, others were intricate works of art featuring dragons, flowers, or family crests (Mon).

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

When drawing the Tsuba from an angle, remember it’s an ellipse, not a circle. It sits between the blade and the handle, held in place by two metal washers called Seppa. If you forget the Seppa, the sword looks like the handle is just glued onto the metal. These small details are what separate a "drawing" from a "technical illustration."

Shading the Hamon: The tempered edge

This is the coolest part. The Hamon is the visible line of the differential hardening. It’s where the steel changes from hard to soft. It can be straight (Suguha) or wavy (Midare).

To draw this effectively:

- Keep your blade shading very smooth and metallic.

- Use a kneaded eraser to "tap" out a cloudy, misty line along the edge.

- The Hamon should look like a frosted pattern, not a solid dark line.

- Use high contrast. The edge of the sword should be the brightest or darkest part depending on your lighting.

Mastering how to draw a samurai sword means respecting the craft of the smiths like Masamune or Muramasa. Their blades weren't just shiny; they had "Nie" and "Nioi"—tiny crystals in the steel that caught the light. You can mimic this with a bit of stippling or very fine cross-hatching near the tempered edge.

The Saya (Scabbard) and the curve match

If you’re drawing the sword inside its scabbard, the Saya, it needs to be slightly thicker than the blade itself. Usually, these were made of magnolia wood and lacquered. The curve of the Saya must perfectly mirror the curve of the blade. If they don't match, the physics of the drawing will feel "off" to the viewer.

Don't forget the Sageo—the hanging cord. It’s usually tied in a complex decorative knot when the sword is on display. It flows. It’s soft. Contrast that softness with the hard, cold steel of the blade.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

Putting it all together into a composition

One trick used by professional illustrators is the "foreshortened" view. Instead of drawing the sword side-on, draw it pointing slightly toward the viewer. This makes the blade look dangerous. It forces you to deal with the perspective of the Tsuba and the tapering of the steel.

Basically, you’re creating a series of receding planes.

If you look at the works of masters like Takehiko Inoue (the creator of Vagabond), you’ll see he treats the sword as a character. He doesn't use a ruler. He uses organic, confident strokes that imply the sharpness.

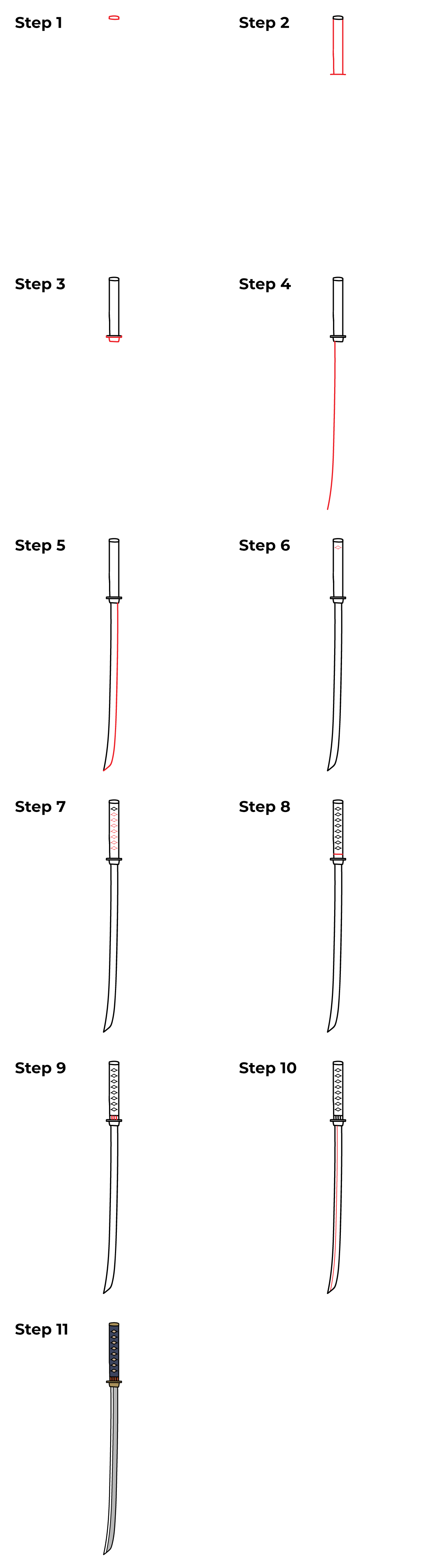

Actionable steps for your next sketch

- Start with the Axis: Draw a curved line for the spine. Don't use a compass; keep it organic.

- The Taper: Add the cutting edge, ensuring the width narrows as it approaches the tip.

- The Yokote: Snap that vertical line at the tip to define the Kissaki.

- The Handle Diamonds: Sketch the Ito wrap using a "diamond" grid rather than simple X-shapes.

- The Hamon: Use a blending stump or your finger to create a smoky, irregular line along the edge.

- Value Contrast: Darken the Tsuba and the Tsuka to make the bright steel of the blade pop.

Drawing a Katana is a lesson in patience. If you rush the handle wrap, the whole piece looks messy. If you mess up the curve, it looks like a scimitar or a machete. Take your time with the silhouette. Once the silhouette is right, the rest is just texture.

Check your reference photos. Look at museum-grade blades from the Tokyo National Museum. Notice how the light doesn't just hit the blade; it follows the Shinogi (the ridge line). If you can capture that one line of light running down the length of the steel, you’ve nailed it.