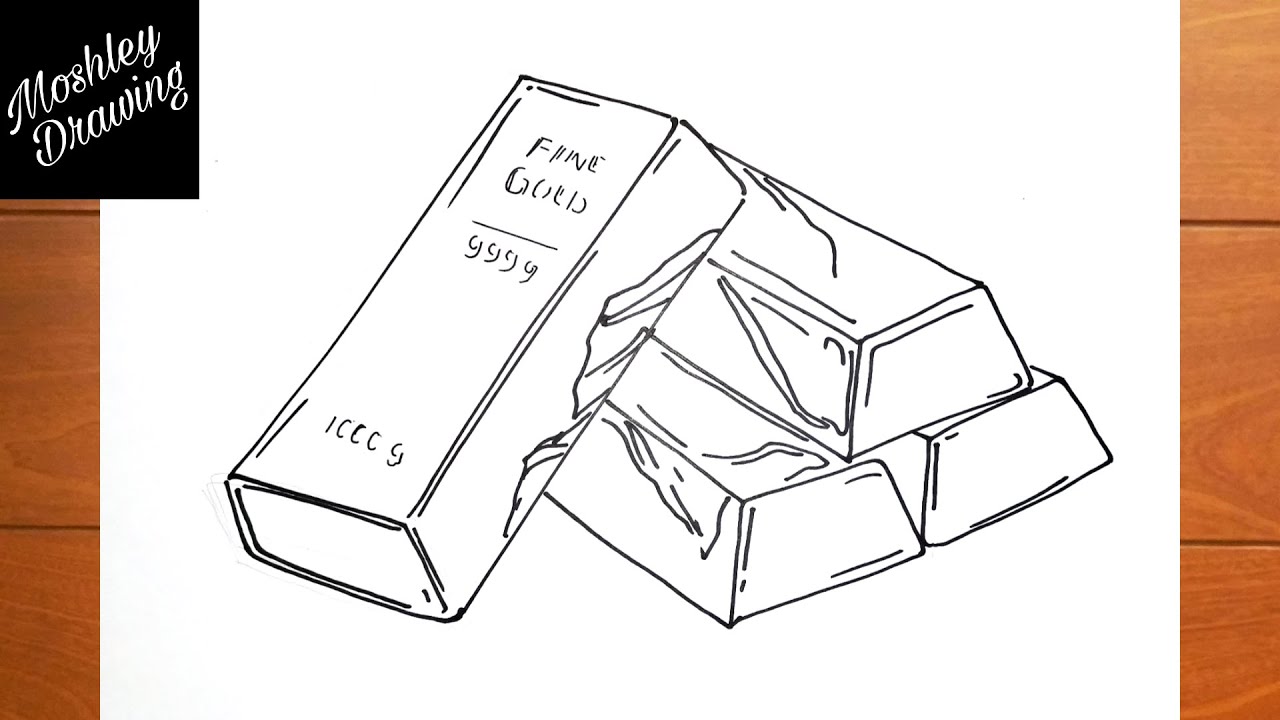

You’ve seen them in heist movies. Thousands of shiny, heavy blocks stacked in a vault, usually being hauled away by someone in a mask. But when you actually sit down to figure out how to draw a gold bar, things get weirdly difficult. It’s a rectangle, right? Well, sort of. If you just draw a yellow box, it looks like a stick of butter or a block of cheese. Gold is different. It has weight. It has a specific reflection. It has those iconic sloped sides that make it look like a "top-down" pyramid with the point cut off.

Honestly, the biggest mistake people make is thinking about color first. It’s not about the yellow. It’s about the physics.

The Geometry of Value: Why Your Proportions Matter

Most people start with a perfect rectangle. Don’t do that. Real gold bars—specifically the "Good Delivery" bars traded on the London bullion market—aren't perfect bricks. They are technically "frustums." That’s a fancy geometry word for a pyramid that had its top sliced off.

Why? Because they need to be removed from a mold. If the sides were perfectly vertical, the gold would get stuck in the cast as it cooled. By drawing the top surface slightly smaller than the base, you immediately signal to the viewer's brain that this is heavy, molded metal.

Start with your vanishing points. If you’re drawing in two-point perspective, your lines should converge toward the horizon. This creates the depth. If you make the lines parallel, the bar will look "flat" or isometric, which is fine for a video game icon but terrible for a realistic illustration. Draw the top face first. Then, drop the vertical lines down, but angle them slightly outward. This subtle flare at the base is what gives a gold bar its "heft."

The "Chisel" Edge

Look closely at a real bar from a mint like PAMP Suisse or the Royal Canadian Mint. The edges aren't razor-sharp. They have a tiny, 45-degree bevel. In the world of art, we call this a "specular highlight" zone. If you draw two lines meeting at a sharp corner, it looks like paper. If you draw a tiny, thin third plane between them, you have a place to put your brightest white paint or pencil mark. That tiny strip of light is what makes the metal look "hard."

Lighting the "Midas" Way

Gold isn't actually yellow. It’s a reflective surface that mimics its environment. If you’re learning how to draw a gold bar, you have to stop thinking about local color.

Think about a mirror. If you put a mirror in a blue room, the mirror looks blue. Gold is a "colored" mirror. It takes the reflections of the room and tints them with a warm, metallic hue. This is why a gold bar in a dark vault looks brown and deep orange, while a gold bar outside looks bright lemon and white.

- The Dark Core: Somewhere in the middle of your bar, you need a high-contrast dark shape. This represents the "ground" or the "room" being reflected.

- The Highlight: Use a crisp, near-white shape right next to your darkest dark. This contrast creates the "glint."

- The Ambient Glow: Gold reflects onto itself. If you have a stack of bars, the bottom of one bar will glow with the yellow light reflecting off the top of the bar beneath it.

I've spent hours looking at high-resolution photos from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Their bars aren't even uniform. Some are "rough-cast," meaning they have a pebbled, sandy texture from the mold. Others are "minted," meaning they are pressed and stamped until they are smooth as glass. Decide which one you're drawing. A rough-cast bar needs more "noise" in the shading—little dots and irregular shadows. A minted bar needs long, clean gradients.

Adding the Details That Prove It’s Real

A blank bar is boring. It looks like a prop. To make it authentic, you need the "markings." Real bullion has specific data points stamped into the surface.

- The Hallmark: This is the logo of the refinery.

- The Purity: Usually "999.9" or "Fine Gold."

- The Weight: "1 Kilo" or "400 oz."

- Serial Number: A unique alphanumeric code.

When you draw these, don't just write them on top. They are "incuse" marks, meaning they are stamped into the metal. This means the top edge of each letter should have a tiny shadow, and the bottom edge should have a tiny highlight. It’s the opposite of how you’d draw a raised button. This "pitting" effect makes the gold look dense. If you just draw black letters on the yellow surface, it looks like a sticker.

Texture and Imperfections

Gold is soft. It’s one of the most malleable metals on Earth. Real bars that have been moved around in armored trucks have "bruises." They have tiny nicks on the corners. They have "pouring lines"—faint ripples on the top surface where the molten metal cooled in waves. Adding one or two of these tiny imperfections will do more for your drawing’s realism than ten hours of perfect shading. It tells a story. It says this bar has been handled, weighed, and traded.

Step-by-Step Implementation for Your Canvas

First, grab a hard lead pencil, like a 2H. You want light lines because you’re going to be erasing a lot of your perspective guides. Map out the "box" using the tapered side method we talked about.

Once the shape is there, identify your light source. If the light is coming from the top left, your top face will be the lightest, the front face will be a mid-tone, and the right side will be your darkest shadow. But wait—because it’s metal, you need to "break" those rules. Throw a bright "bounce light" on the very edge of the shadow side. This represents light hitting the table and bouncing back into the gold.

💡 You might also like: The Bond: Why Lynne McTaggart’s Vision of Connection Still Matters in 2026

If you’re using digital tools like Procreate or Photoshop, use a "Metallic" brush or a hard airbrush. Avoid soft, fuzzy brushes; they make gold look like glowing gas or yellow clouds. Metal is hard. It needs hard edges.

Use a "Color Dodge" layer for the final highlights. This is the "secret sauce" for digital gold. Take a light orange color, set the layer to Color Dodge, and hit the corners of the bar. It will look like the gold is actually catching the sun.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Over-Saturating: Don't just use the brightest yellow in your box. It looks "fake." Real gold has a lot of brown, tan, and even weird greenish-grey in the shadows.

- Ignoring the Surface: If the bar is sitting on a black velvet cloth, the bottom of the bar should reflect black. If it’s on a wooden table, the bar should have brownish-orange reflections.

- Perfect Symmetry: Even the best bars have a slight "slump" or a microscopic curve to their faces due to surface tension when the gold was liquid. A perfectly straight line looks "digital." A very, very slight curve looks "heavy."

Putting It Into Practice

Now that you understand the "why" behind the shape, the best thing to do is a "value study." Take a scrap of paper and try to draw three different bars under three different light sources. One in a dark room with a single spotlight. One in an open field under a blue sky. One in a neon-lit "cyberpunk" setting. You’ll find that the "goldness" of the bar comes from the contrast, not the pigment.

Next Steps for Your Artwork:

- Sketch the "Frustum": Draw a rectangle for the top, a larger one for the base, and connect them with angled lines to establish that heavy, tapered look.

- Map the Highlights: Before shading, outline where the brightest reflections will go—usually along the top edges and the corners.

- Layer Your Tones: Start with a "burnt sienna" or deep ochre for the shadows, then layer a "cadmium yellow" for the mid-tones, leaving the highlight areas completely white or very pale cream.

- Stamp the Identity: Use a fine-liner or a sharp pencil to "carve" a serial number and a ".999" purity mark into the face, adding a tiny shadow to the top of each stroke to create depth.

- Ground the Object: Add a cast shadow on the surface below the bar. Because gold is reflective, the shadow should actually be "warm" near the base of the bar, as yellow light bounces off the gold and into the shadow area.

By focusing on the physical properties of the metal rather than just the color yellow, you’ll create an image that feels like it has actual monetary value. Experiment with different "finishes"—from the polished mirror look of a modern investment bar to the rough, "sunken treasure" look of an ancient Spanish cob. The principles remain the same: shape, reflection, and weight.