You see them every single day. They sit on the corner, usually chipped, maybe a little rusty, and mostly ignored by everyone except dogs and the occasional city maintenance crew. But have you actually tried to sit down and draw one? It’s harder than it looks. Most people just sketch a red pill shape with some arms and call it a day. Honestly, that’s why their drawings look like cartoons rather than real objects. If you want to learn how to draw a fire hydrant that actually looks like it belongs on a street corner in Chicago or New York, you have to look at the engineering, not just the shape.

Industrial design is weirdly specific.

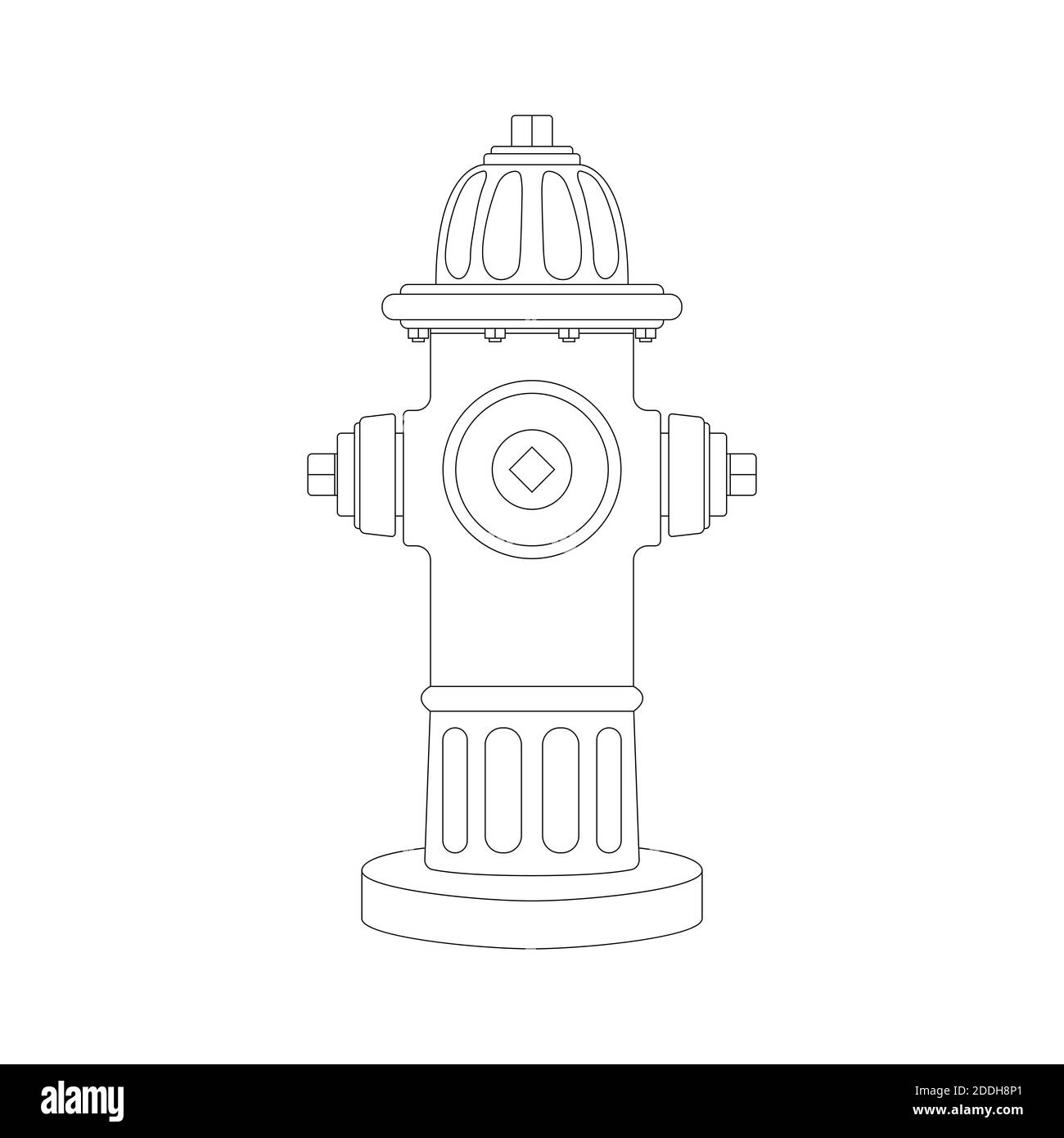

Fire hydrants—specifically the "dry barrel" ones common in colder climates—are built to withstand thousands of pounds of water pressure and the occasional distracted driver. When you're sketching, you aren't just drawing a cylinder. You're drawing a series of heavy, cast-iron components bolted together. If you miss the "bonnet" or the "flange," the whole thing feels off.

The anatomy of a hydrant (and why it matters for your sketch)

Let’s get real about the structure. A fire hydrant isn't one solid piece of metal. It's a vertical assembly. At the very top, you’ve got the bonnet. This is the "hat" of the hydrant. It’s usually a slightly flared dome. Right in the middle of that dome is the operating nut. Usually pentagonal. Why five sides? So regular wrenches won't fit. Only the fire department’s special wrench does the trick.

Draw the nut first. If you get the perspective of that pentagon wrong, the rest of the hydrant will look like it’s leaning.

Below the bonnet is the upper barrel. This is the main body. It’s where the nozzles live. Most hydrants have three: two smaller "hose nozzles" on the sides and one big "pumper nozzle" in the front. These aren't just stuck on like stickers. They are heavy-duty outlets with threaded caps. Those caps are almost always attached to the body by a heavy iron chain. If you forget the chains, you lose 50% of the realism immediately.

Then there’s the flange. This is the thick ring where the upper barrel meets the lower part of the hydrant. It’s held together by a circle of massive bolts. In a drawing, these bolts provide excellent "contour lines." They wrap around the form and show the viewer exactly how the cylinder is curving in space.

📖 Related: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Lighting the cast iron surface

Cast iron has a specific texture. It’s not smooth like a smartphone or a car hood. It’s slightly pitted. Gritty. When light hits a painted fire hydrant, it doesn't create a perfect, sharp highlight. It’s a bit diffused.

You’ve probably seen hydrants painted bright red, but did you know the colors actually mean something? According to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) 291 standards, the color of the caps often indicates the flow rate (gallons per minute).

- Blue: 1,500 GPM or more.

- Green: 1,000–1,499 GPM.

- Orange: 500–999 GPM.

- Red: Less than 500 GPM.

So, if you’re coloring your drawing, picking a color isn’t just an aesthetic choice. It’s a technical one. A blue-capped hydrant tells a story of high-pressure water supply.

Step-by-step: How to draw a fire hydrant with depth

Start with a vertical axis line. Just a light stroke. This is your spine.

Draw three horizontal ellipses. One for the top of the bonnet, one for the flange in the middle, and one for the base where it meets the sidewalk. Make sure the "roundness" (the degree) of these ellipses increases as they move below your eye level. If you are looking down at the hydrant, the bottom ellipse will be much rounder than the top one. This is basic perspective, but it's where most people mess up.

Next, define the "pumper nozzle" in the center. Think of it as a smaller cylinder intersecting a larger one. Where they meet, there’s a curved seam. Don't just draw a straight line. That seam should follow the curve of the hydrant's body.

👉 See also: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

Getting the "shoulder" right

The area where the barrel widens to meet the nozzles is often called the "shoulder." It’s a subtle transition. Instead of a sharp corner, use a soft, sloping curve. This is where the cast iron is thickest to handle the pressure.

Now, add the chains. Don't draw every single link perfectly. That looks stiff. Just suggest the shape of the links with "S" and "C" strokes. Let them sag. Gravity is your friend here. It makes the object feel heavy.

Shadows are the final boss. Since hydrants are usually outdoors, you’re dealing with sunlight. This means a sharp "core shadow" on one side and a "cast shadow" on the ground. But don't forget reflected light. The sidewalk is a giant reflector. It bounces light back up into the underside of the nozzles. Adding a small sliver of lighter value at the very bottom edge of the nozzles will make them pop off the page.

Common mistakes you're making

Stop making the nozzles perfectly horizontal. On many models, like the classic Mueller Super Centurion, the nozzles actually tilt slightly downward or upward. Look at a reference. If you draw them perfectly straight like Shrek’s ears, it looks like a toy.

Another big one: the base. Fire hydrants don't just sit on the concrete. They are bolted to it or emerge from it. There’s usually a "bury line" marked on the barrel. This is the point where the hydrant is supposed to be level with the ground. Often, there’s a bit of dirt, weeds, or cracked pavement around the bottom. Drawing that transition makes the object feel grounded in a real environment.

Tools of the trade

If you're working with pencil, use a 2B for the initial lay-in and a 6B for those deep, dark crevices around the bolts and under the cap. If you're digital, use a brush with a bit of "tooth" or grain. A perfectly smooth digital airbrush will make the hydrant look like it's made of plastic. You want it to look like it could break a toe if you kicked it.

✨ Don't miss: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

Realism comes from the imperfections. The chipped paint where a wrench has hit the nut. The slight rust streak running down from a bolt. These are the things that tell the viewer, "This is a real object in the real world."

Why we draw these things anyway

Drawing mundane objects is the best way to train your "artist's eye." We think we know what a fire hydrant looks like because we see them every day. We don't. We see a symbol of a hydrant. When you sit down to actually render the how to draw a fire hydrant process, you’re forced to see the reality of the object. You notice the hex bolts. You notice the way the light catches the curved metal. You notice the weirdly specific shape of the nozzle caps.

It’s a masterclass in drawing cylinders and spheres.

Most people fail because they rush the "boring" parts. They want to get to the bright red color. But the "boring" parts—the bolt placement, the ellipse degree, the flange thickness—are what actually make the drawing work.

Actionable Next Steps

- Go outside. Find the nearest hydrant. Don't just take a photo. Walk around it. Look at how the nozzle chains are attached. Note the brand name cast into the side (Mueller, Kennedy, and Clow are common ones).

- Sketch the "skeleton" first. Use the three-ellipse method to lock in your perspective before you even think about the nozzles.

- Practice the pentagon. The five-sided operating nut is the hardest part. Practice drawing pentagons in perspective until they don't look like lopsided squares.

- Layer your textures. If using color, start with a dark rust-brown base in the shadows, layer your red (or blue/green) over it, and then use a dry brush to "scuff" the edges where the paint would naturally wear off.

- Ground the object. Always draw at least six inches of the sidewalk or grass around the base to provide context and scale. This prevents the "floating object" syndrome that kills most amateur sketches.