Drawing a profile is weirdly intimidating. Most people start by sketching a nose and then realize they’ve run out of room for the brain. It’s a classic mistake. You end up with a "flat-head" look because our brains are naturally biased toward the face—the eyes, the mouth, the expression—while completely ignoring the massive chunk of skull sitting behind the ears. If you want to learn how to draw a face from the side, you have to stop looking at the features and start looking at the architecture.

The human head isn't a circle. It’s more like a ball with the sides sliced off, attached to a mechanical hinge. When you look at a profile, you’re seeing the most honest version of a person’s bone structure. There’s no hiding behind "pretty eyes" here. You’ve got to get the distances right or the whole thing falls apart. Honestly, once you nail the relationship between the ear and the jaw, everything else just kinda falls into place.

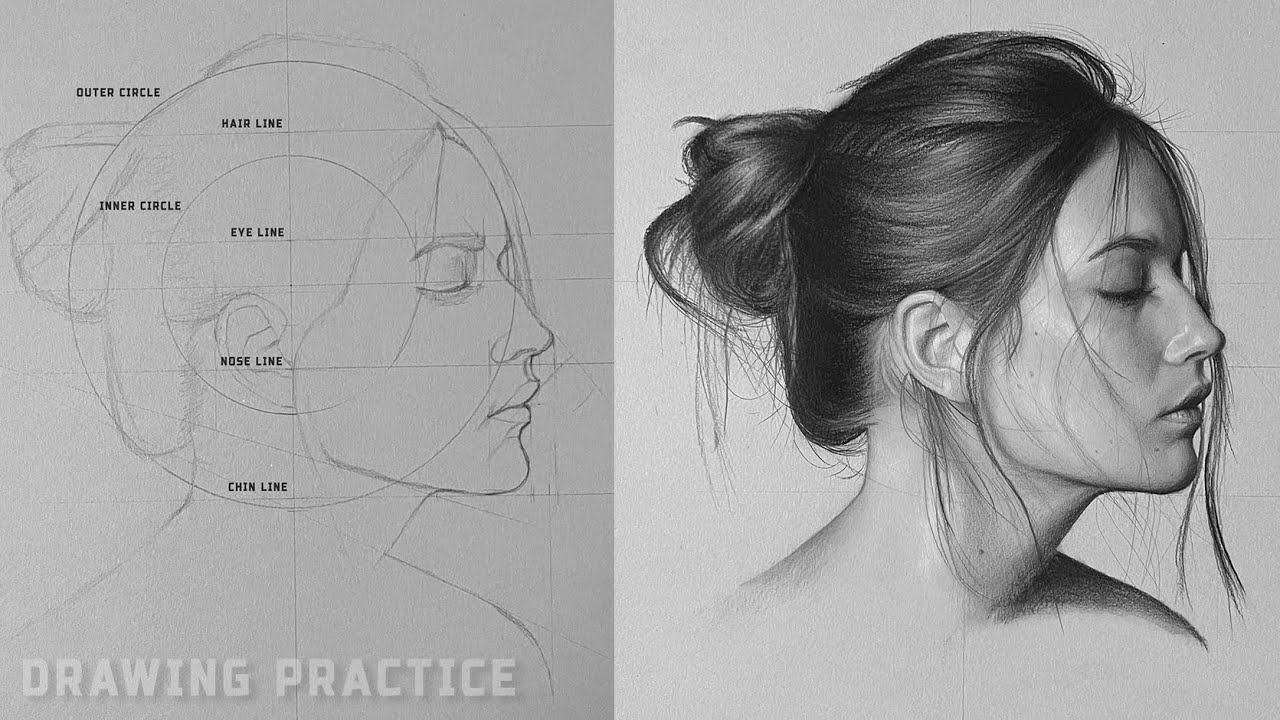

The Loomis Method vs. Reality

Most art students eventually stumble upon Andrew Loomis. His 1943 book, Fun with a Pencil, is basically the bible for this stuff. Loomis suggests starting with a circle and then lopping off the sides to account for the flat planes of the skull. It's a solid foundation. But here’s the thing: real people don’t always fit into perfect 1940s illustrative boxes.

🔗 Read more: Sir and Star at the Olema House: Why This Marin County Spot Still Feels Like a Secret

When you're figuring out how to draw a face from the side, the circle represents the cranium. But the face itself hangs off the front of that circle. If you draw the features inside the circle, your character will look like they’ve been hit with a frying pan. You need to extend the jaw downward. The distance from the top of the head to the eyebrow line is usually roughly equal to the distance from the eyebrows to the bottom of the nose, and from the nose to the chin. This is the "Rule of Thirds," and while it’s a great guideline, it varies wildly between ethnicities and ages.

Look at someone like Robert Munch. He’s a well-known anatomy expert who emphasizes that the ear is the "anchor" of the profile. Most beginners put the ear too far forward. In reality, the ear sits right behind the midline of the head. If you divide your initial sphere into four quadrants, the ear lives in the bottom-back quadrant, nestled right where the jawbone begins its upward climb.

The Profile’s Secret: The "S" Curve

If you trace the silhouette of a face, it’s a series of rhythmic ins and outs. It’s not a straight line. Never.

The forehead reaches out, then dips at the bridge of the nose. The nose reaches out further, then tucks back in. Then you have the lips. This is where people get tripped up. The upper lip usually hangs slightly further forward than the lower lip. Think of it like shingles on a roof; the top one overlaps the bottom one to let the "rain" (or light) fall off. Below the lips, the chin kicks back out again before disappearing into the neck.

It's all about the angles. If you draw a straight vertical line from the forehead to the chin, you’ll see that the face actually slants. Some people have a "prognathic" profile where the jaw sticks out, while others have a "retrognathic" profile where the chin retreats. Neither is wrong; they just communicate different character traits. If you’re drawing a hero, you might give them a prominent, square chin. If you’re drawing someone more timid, a receding chin line can tell that story without you saying a word.

Eyes are Not Footballs

Stop drawing the eye as a football shape when you're looking from the side. It’s a triangle.

When you look at a face from the side, you aren't seeing the whole almond shape of the eye. You’re seeing the side of the eyeball tucked under the eyelid. The eyelashes point forward and out. The brow bone actually overhangs the eye quite a bit. If you don't create that "cave" for the eye to sit in, the face will look flat and sticker-like.

The Neck Isn't a Pillar

One of the biggest giveaways that an artist is a beginner is how they attach the head to the body. Necks don't come straight out of the bottom of the skull like a lollipop stick. They lean.

The neck actually slants forward. It starts at the base of the skull (way higher up than you think) and moves toward the collarbone. On the back, you have the trapezius muscle sloping down toward the shoulders. On the front, the throat follows the line of the jaw. If you draw the neck as two vertical lines, your character will look like a robot. You’ve gotta give it that natural, organic tilt.

Actually, the "Adam's Apple" or laryngeal prominence is a great landmark here. In men, it’s usually much more sharp and visible, sitting right at the midpoint of the neck’s front edge. In women, the curve is softer, but the forward lean of the neck remains the same.

The Jawline and the "Mantle"

The jaw is a hinge. It hooks in just in front of the ear. When you're learning how to draw a face from the side, you need to feel that corner—the "angle of the mandible."

- Sketch the circle for the cranium.

- Drop a vertical line down from the center.

- Mark the chin point.

- Connect the chin back to the "corner" of the jaw, which sits just below and slightly in front of the earlobe.

This creates a clear separation between the face and the neck. This area under the jaw is often in shadow. If you want your drawing to pop, use a darker tone right under that jawline. It defines the structure immediately.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

I’ve seen a thousand drawings where the back of the head is missing. People get so focused on the nose and mouth that they forget there’s a whole brain back there. The distance from the bridge of the nose to the back of the head is roughly the same as the distance from the top of the head to the chin. It’s a square, basically. If your drawing looks like a thin slice of bread, you need to add more "back" to the skull.

Another thing? The mouth. The corner of the mouth usually aligns with the front of the eye (the iris) when looking straight on, but in profile, it’s tucked back. It’s a small, v-shaped notch. Don't draw the whole mouth; just draw the silhouette of the lips and a tiny crease for the corner.

💡 You might also like: Bissell Spot and Stain Cleaner: Why Your Carpet Still Looks Dingy

And the hair. Please, don't just draw lines on top of the head. Hair has volume. It sits on top of the skull. If you’ve drawn your skull correctly, the hair should add another half-inch of height and width. It follows the flow of the scalp but exists as its own mass.

Practical Steps for Your Next Sketch

Start with a light touch. Use a 2B pencil or a light grey digital brush.

First, draw a circle. Don't worry about it being perfect. Divide it in half vertically and horizontally. This horizontal line is your brow line. It’s not the eye line! The eyes sit slightly below this.

Next, find the "side plane." Draw a smaller circle inside your first one. This represents the flat side of the head where the temple and ear live. The ear will go in the back-bottom quadrant of this smaller circle.

Now, extend the jaw. Drop a line down from the front of your big circle. Use the "rule of thirds" to find the nose and chin. Once you have these marks, connect them. Nose to lips, lips to chin, chin to jaw corner, jaw corner to ear.

📖 Related: Temperature in New Jersey in Degree Celsius: What Most People Get Wrong

Finally, add the features. Keep them simple. A wedge for the nose. A triangle for the eye. Two small curves for the lips.

Refine the silhouette. Look at the transition from the forehead to the nose. Is it a sharp drop or a smooth curve? Every person is different. Adjust your lines to match a reference photo.

Check your distances. Is the ear too high? It should generally align between the eyebrows and the bottom of the nose. If it’s up by the eyes or down by the mouth, it’ll look "off," even if you can't quite pin down why.

Add the neck tilt. Remember, it’s an angle, not a pillar. Make sure the back of the neck starts at the base of the skull, not at the chin.

By focusing on these structural landmarks rather than "pretty" features, your profiles will immediately gain a sense of weight and realism that most beginner sketches lack.