You’ve probably seen those "how to draw" books that start with a perfect circle. They tell you to divide it into four equal quarters, drop a chin down, and suddenly—boom—you’re supposed to have a masterpiece. It’s frustrating. Honestly, most of those tutorials fail because they treat the human face like a geometry problem instead of a character. If you want to learn how to draw a cartoon head, you have to stop thinking about symmetry and start thinking about squash and stretch.

Cartooning isn't just "bad drawing" done on purpose. It is the art of simplification and exaggeration. Whether you’re looking at the rubber-hose style of the 1930s or the sharp, angular designs of modern CalArts animation, the fundamentals remain the same. You need a solid foundation. But that foundation shouldn't be a cage.

The Loomis Method vs. The "Big Shape" Approach

Most professional illustrators, like the legendary Andrew Loomis, preach the "ball and plane" method. It’s a classic for a reason. You start with a sphere, chop off the sides to represent the temples, and add a jawline. It works beautifully for realism. However, when you’re trying to figure out how to draw a cartoon head, sticking too strictly to Loomis can make your characters look stiff. They look like mannequins.

🔗 Read more: Amazon Prime Automatic Refunds: What Actually Happens to Your Money

Try this instead: Start with a bean. Or a lightbulb. Or a pear.

Preston Blair, an animator who worked on Bambi and Fantasia, famously used "construction shapes" that were far more organic than a simple circle. If you look at his original sheets, he’s often building heads out of two overlapping circles of different sizes. This creates an automatic "cheek" or "muzzle" area. It gives the head volume before you even draw a single eyelash.

The trick is depth. You aren't drawing a flat circle; you’re drawing a bowling ball. Imagine those blue "contour lines" wrapping around the shape. If you can’t "feel" the back of the head while you’re drawing the front, the character will always look like a paper cutout.

Why Your Proportions Feel "Off" (and How to Fix Them)

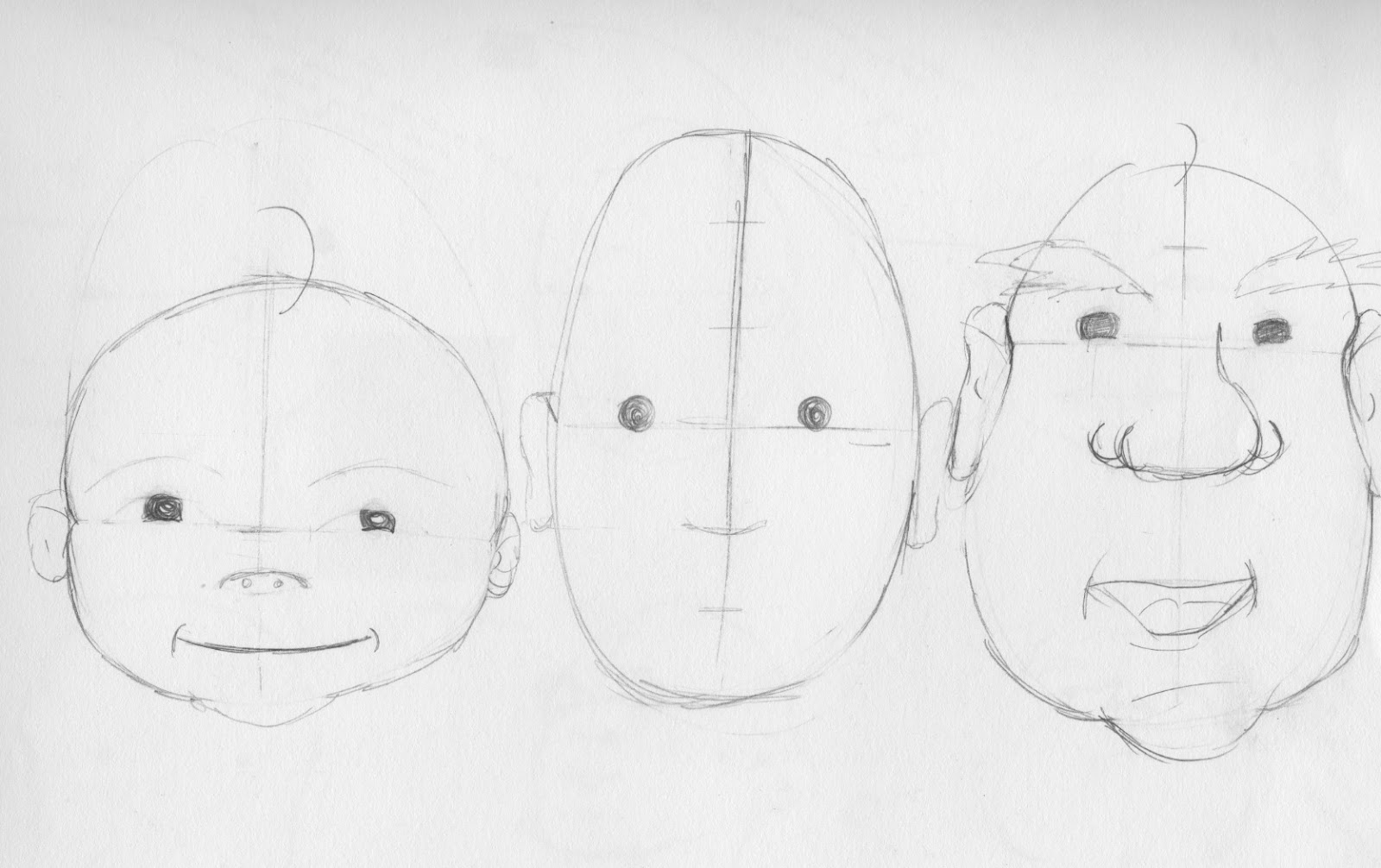

In a real human head, the eyes sit right in the middle of the skull. Beginners hate hearing this. They always want to put the eyes at the very top, leaving no room for the forehead or the brain. In cartoons, you can break this rule, but you have to break it with intention.

If you’re struggling with how to draw a cartoon head that looks balanced, look at the "Rule of Thirds" in character design. Usually, the face is divided into the forehead, the nose section, and the mouth/chin section. To make a character look "cute" or "baby-like," you expand the top third and shrink the bottom two. This is why Mickey Mouse or Boss Baby have massive foreheads and tiny little chins. It triggers a biological "must-protect" response in our brains.

On the flip side, if you want a villain or a "tough guy," you do the opposite. Give them a massive, protruding jaw and a tiny sliver of a forehead. Think of characters like Brock Samson from The Venture Bros. or even the classic Desperate Dan. By shifting where the features sit on that initial "bean" shape, you tell the audience exactly who this person is before they even speak a word.

The Secret is the T-Shape

Here is a pro tip that most YouTube tutorials skip over: The T-Shape.

Basically, the "T" is the relationship between the brow line and the bridge of the nose. It is the anchor of the entire face. If you get the T-shape right, you can move the eyes and mouth anywhere you want and the head will still look "right."

- Draw your main head shape (the "flour sack" or "egg").

- Find the "mid-line" that runs down the center of the face.

- Cross it with the "eye-line."

- Where they intersect is the bridge of the nose.

When the character looks up, that T-shape shifts upward and curves. When they look down, it squashes toward the bottom. If you keep the nose locked into that intersection, the features won't "drift" across the face when you start animating or drawing different angles.

Stop Drawing Individual Teeth

Nothing kills a cartoon head faster than drawing every single tooth. It looks creepy. It’s what artists call the "Uncanny Valley." Unless you are going for a specific, grotesque style (like Ren & Stimpy), treat the teeth as a single white shape. Maybe add one or two suggestive lines to show where the front teeth are, but keep it simple.

The same goes for hair. Beginners try to draw every strand. Don't do that. You’ll go crazy. Think of hair as a "helmet" or a solid mass that sits on top of the skull. Draw the big shape of the hair first, then add a few "flick" lines to show texture. If you look at Glen Keane’s sketches for Tangled or Tarzan, he focuses on the "flow" and "rhythm" of the hair mass rather than individual hairs. It’s about the silhouette.

👉 See also: How to Format Mail: What Everyone Gets Wrong About Sending Letters and Packages

How to Draw a Cartoon Head from Different Angles

The "three-quarter view" is the gold standard in animation. It’s more dynamic than a profile and more interesting than a straight-on shot. But it’s also the hardest to master.

The biggest mistake people make in 3/4 view? The "far eye."

When a head turns away from you, the eye on the far side of the face gets narrower, not shorter. It also sits closer to the bridge of the nose because the curve of the face is hiding the "inner" corner of the eye. If you draw both eyes the same size in a 3/4 view, the face will look like it’s sliding off the skull.

The "Squash and Stretch" of Expressions

Cartoons are made of rubber. Even when a character is just talking, their whole head should be reacting. When they open their mouth wide to scream, the entire head shape should stretch vertically. The eyes might squint, and the ears might even pull down. When they’re surprised, the head "squashes" down as the eyebrows shoot up.

This is a concept from the "12 Principles of Animation" by Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston. Even in a static drawing, implying this movement makes the head feel alive. If you draw a "neutral" head and just change the mouth, it looks like a cheap puppet. If you change the shape of the skull to match the emotion, you’re a cartoonist.

Actionable Next Steps to Level Up

You won't get better by just reading this. You need to get some lead on paper. Or pixels on a screen. Here is exactly how to practice:

- The "Sheet of 50": Grab a piece of paper and draw 50 different shapes. Ovals, triangles, blobs, "D" shapes. Don't think about faces yet. Just fill the page.

- The Feature Toss: Go back to those 50 shapes and drop a T-shape into each one at a random angle. Some looking up, some looking down, some tilted.

- Add the Features: Now, add eyes, a nose, and a mouth based on those T-shapes. Don't worry about making them look "good." Just make them look consistent with the perspective.

- The Silhouette Test: Fill in your finished cartoon head with solid black. Can you still tell what the character is feeling? If the nose, chin, and hair create a clear, recognizable outline, you’ve nailed the design.

- Reference Real People: Sit in a coffee shop or a park. Look at real people and try to "caricature" them. If someone has a large nose, draw it twice as big. If someone has tiny glasses, draw them like pinpricks. This trains your brain to see the "big shapes" in reality.

The best cartoonists aren't the ones who can draw a perfect circle. They're the ones who aren't afraid to draw a really weird, lopsided circle and turn it into something with a soul. Grab a pencil and start making a mess. Focus on the volume, trust the T-shape, and remember that in the world of cartoons, "perfect" is usually boring.

Once you have the basic head structure down, start experimenting with line weight. Use thicker lines for the outer silhouette and thinner lines for the interior details like eye wrinkles or the bridge of the nose. This "weighted" look adds immediate professional polish and helps the character "pop" off the background. Keep your sketches loose and avoid using an eraser until the very end; those "mistake" lines often contain the energy that makes a cartoon feel truly dynamic. Drawing is a physical skill, so keep the muscle memory building by sketching at least ten quick heads every day. Over time, your hand will start to find the shapes automatically.