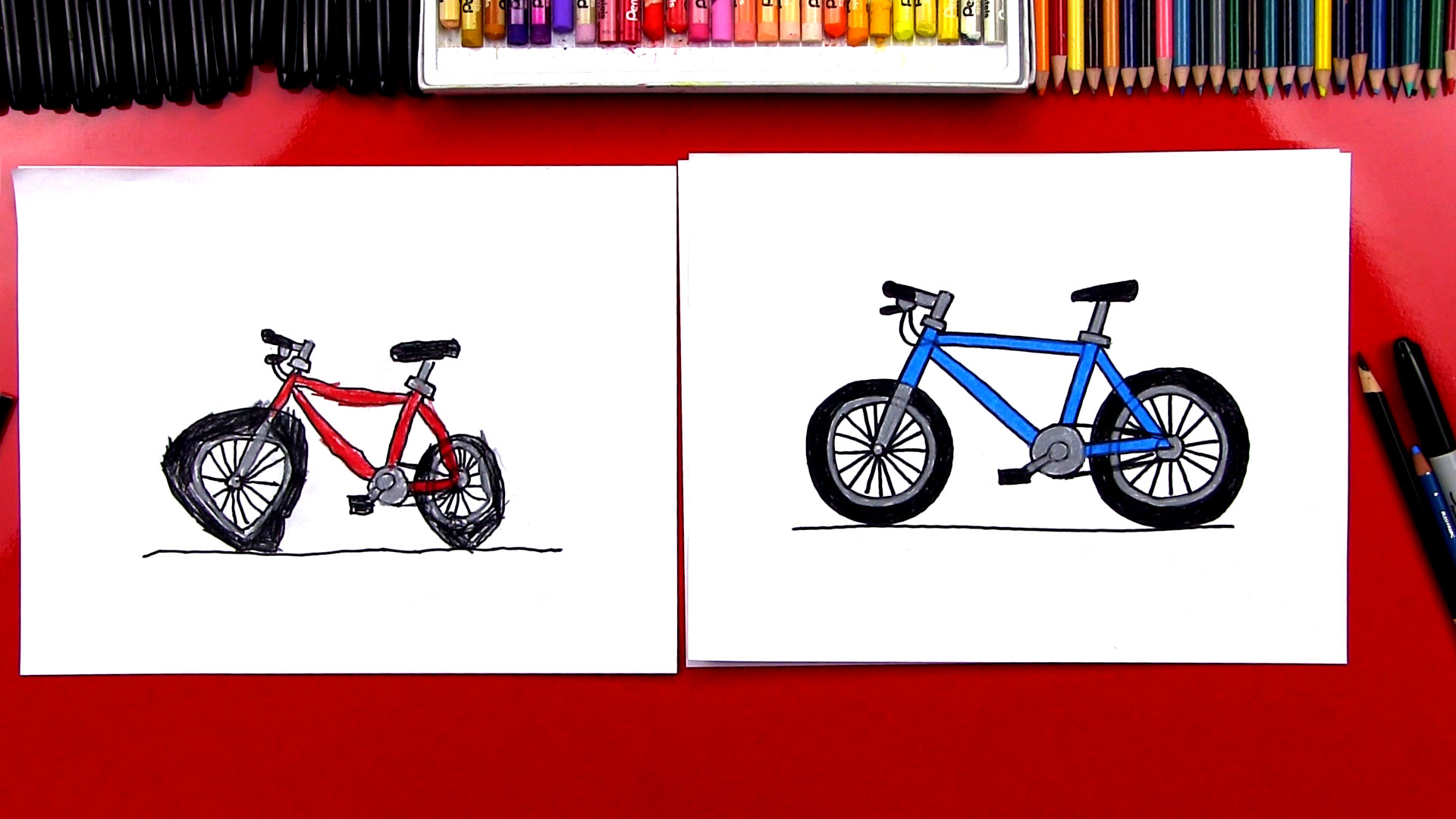

You’ve probably seen that social experiment where people are asked to draw a bicycle from memory. Most people fail. Badly. They attach the chain to the front wheel or forget the frame needs to be made of triangles to actually support a human being. It’s hilarious until you try to do it yourself and realize your brain has been lying to you about what a bike actually looks like for twenty years. If you want to learn how to draw a bike, you have to stop drawing what you think you see and start looking at the mechanical skeleton that makes the machine work.

Drawing a bike is basically a masterclass in perspective and proportion. It’s hard. Honestly, it’s one of the most frustrating things for beginners because there is nowhere to hide a mistake. If an eye is slightly off in a portrait, it’s "character." If a bike frame is off, the whole thing looks like it melted in the sun.

The Secret is the Invisible Diamond

Most people start with the wheels. That’s a mistake. While the wheels give you the scale, the heart of the bicycle is the frame geometry. Professionals often refer to the "double diamond" design. It’s been the standard since the late 19th century because triangles are incredibly strong and don't deform under stress.

Think of it this way: You have a front triangle and a rear triangle. The front one is usually more of a quadrilateral if we're being pedantic, consisting of the seat tube, the top tube, the down tube, and the head tube. The rear triangle consists of the seat stays and the chain stays.

When you start your sketch, keep your lines light. Use a hard lead pencil like a 2H. You’re going to be erasing a lot. Start by marking the centers of your two wheels. The distance between these two points—the wheelbase—is usually about three times the radius of the wheel itself. If you get this distance wrong, the bike will look like either a circus prop or a stretched-out limousine.

Why the "Stick Figure" Approach Fails

We tend to draw bikes as a series of sticks. But a bike has volume. The tubes have thickness. The "head tube"—that little vertical-ish pipe that holds the handlebars—needs to be angled. If it’s perfectly vertical, the bike would be unrideable in real life. It needs "rake" or "trail." Look at a Trek Domane or a Specialized Tarmac. Notice how that front fork slants forward. That angle is what keeps a rider from falling over the moment they let go of the bars.

✨ Don't miss: Deep Wave Short Hair Styles: Why Your Texture Might Be Failing You

Mastering the Circular Nightmare

Circles are the enemy. Everyone hates drawing them. To get the wheels right for your bike drawing, don't just whip a compass around and call it a day. Wheels have depth. If you’re drawing the bike from a slight angle—which you should, because side profiles look flat and boring—those circles become ellipses.

- The Hub: This is the center point. Everything radiates from here.

- The Rims: They have a thickness. Don't just draw a single line.

- The Tires: Think about the tread. A mountain bike tire has chunky knobs; a road bike tire is a smooth sliver.

Spokes are where most people give up and start scribbling. Don't do that. You don't need to draw all 32 or 36 spokes. Suggestion is better than literalism. Draw the leading spokes in groups of two or four. Let the others fade into a light gray wash. This creates the illusion of motion and prevents the drawing from looking like a spiderweb.

The Mechanical Bits: Chains and Derailleurs

This is where the "how to draw a bike" challenge gets real. The drivetrain. You have the chainring (the big gear by the pedals) and the cassette (the pile of gears on the back wheel). They are connected by the chain.

Please, for the love of all things holy, do not draw the chain connecting the front wheel to the back wheel. I've seen it in professional advertisements and it physically hurts to look at. The chain stays on the right side of the bike (the "drive side").

The crankset—the arms that hold the pedals—should be drawn at opposing angles. If one is at 12 o'clock, the other is at 6 o'clock. This seems obvious until you’re mid-sketch and suddenly realize you’ve drawn a bike that would require the rider to hop like a bunny to move forward.

🔗 Read more: December 12 Birthdays: What the Sagittarius-Capricorn Cusp Really Means for Success

Handlebars and Human Touch

Handlebars are curvy, organic, and difficult. Drop bars (on road bikes) look like RAM horns. Flat bars (on mountain bikes) have a slight "sweep" back toward the rider.

The biggest tip for the cockpit? Draw the cables. Most modern bikes have internal routing, but seeing a bit of brake housing or a shifter cable adds a level of realism that screams "I actually know what a bike is." It grounds the drawing in reality. It makes it look like a machine that actually functions.

Common Pitfalls and How to Dodge Them

One thing people often miss is the "bottom bracket." That’s the junction where the seat tube, down tube, and chain stays meet. It’s the densest part of the frame. It needs to look sturdy. If you draw it too thin, the bike looks like it’s made of toothpicks.

Another weird detail: the saddle. Don't draw it like a chair. A saddle is a narrow, aerodynamic wedge. It should be roughly level. If it's pointing too far up or down, your "rider" is going to have a very uncomfortable time.

Lighting and Texture

Bikes are usually made of metal or carbon fiber. That means reflections. If you're using ink or colored pencils, leave "hot spots" of white paper to show where the light hits the top tube. Carbon fiber has a matte, deep finish, while older steel frames might have a high-gloss luster with chrome accents on the lugs.

💡 You might also like: Dave's Hot Chicken Waco: Why Everyone is Obsessing Over This Specific Spot

If you're drawing a gravel bike, add some mud splatter. Use a stiff brush to flick some brown paint or ink near the bottom bracket and the underside of the down tube. It adds "story." A clean bike is a boring bike.

Getting the Perspective Right

If you’re struggling, try the "Box Method." Imagine the bike fits inside a long, rectangular crate. Draw the crate in perspective first. Then, map out where the wheels touch the "floor" of that crate. This prevents the dreaded "floating wheel" syndrome where one tire looks like it's six inches higher than the other.

Drawing a bike is honestly a bit of a workout for your brain. It forces you to understand mechanical linkages and 3D space. But once you nail that double-diamond frame and get the ellipses of the wheels to sit right on the ground, it's incredibly satisfying.

Actionable Next Steps for Your Sketchbook

- Find a reference photo that isn't a perfect side profile. Three-quarters view is the sweet spot for showing depth.

- Ghost in the triangles. Don't draw tubes yet. Just draw the lines connecting the hub, the seat, and the handlebars.

- Use a "clock" for the spokes. Mark 12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock first to keep the spacing even.

- Check your crank arms. Ensure they are 180 degrees apart.

- Vary your line weight. Make the lines of the frame thicker and the lines of the spokes and cables thinner. This creates visual hierarchy and keeps the image from looking cluttered.

- Focus on the "negative space." Look at the shapes between the tubes. If those triangles look weird, the whole bike is weird.

Stop worrying about making it perfect on the first go. Even the pros at Pixar or Disney struggle with bicycles. They are notoriously difficult. Just keep your eraser handy and remember: triangles, ellipses, and don't forget the chain goes on the right.