You're staring at a wave. Maybe it’s a sound wave in a digital audio workstation, or maybe it’s just a homework problem that feels way more complicated than it needs to be. You have the sine value, but for whatever reason—coding a game engine, balancing a bridge, or just passing a trig quiz—you need the cosine.

It’s easy to get lost in the Greek letters. How to convert from sin to cos isn't just about memorizing a single formula; it’s about understanding that these two functions are essentially the same shape, just playing a never-ending game of tag. They’re "co-functions." That "co" actually stands for complementary.

Let's be real: math notation makes this look intimidating. It isn't. If you can subtract a number from 90, you can do this.

The Phase Shift: Why They Look So Similar

If you graph $y = \sin(x)$ and $y = \cos(x)$, you’ll notice something immediately. They are identical waves. If you took the sine wave and slid it to the left by about 1.57 units (which is $\pi/2$ in radians), it would lay perfectly on top of the cosine wave.

This is the "Phase Shift."

The most direct way to handle this is the cofunction identity. It’s the bread and butter of trigonometry. Basically, the sine of an angle is the cosine of its complement.

🔗 Read more: UiPath Stratospheric Valuation Emberslasvegas: What Most People Get Wrong

For degrees, the formula looks like this:

$$\sin(\theta) = \cos(90^\circ - \theta)$$

If you’re working in radians (which most programmers and engineers do), it’s:

$$\sin(\theta) = \cos\left(\frac{\pi}{2} - \theta\right)$$

Think about a standard 30-60-90 triangle. The sine of $30^\circ$ is $0.5$. What’s the cosine of $60^\circ$? It’s also $0.5$. Because $90 - 30 = 60$. It’s that simple.

When the Pythagorean Identity is Better

Sometimes you don't know the angle. You just have the value of the sine itself. Maybe your calculator says $\sin(x) = 0.6$ and you need the cosine, but you aren't allowed to find $x$ first.

This is where Pythagoras helps us out. You remember $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$, right? On a unit circle, the radius is $1$. The horizontal side is $\cos$ and the vertical side is $\sin$.

So, we get:

$$\sin^2(\theta) + \cos^2(\theta) = 1$$

To find the cosine from the sine, you just rearrange the furniture. Subtract the sine squared from $1$ and take the square root.

$$\cos(\theta) = \pm\sqrt{1 - \sin^2(\theta)}$$

Wait, why the plus or minus? This is where people usually mess up. A sine value of $0.5$ could happen in the first quadrant or the second quadrant. But the cosine value would be positive in the first and negative in the second. You have to know where your angle lives. If you’re building a physics engine and your object is moving "backwards" on the x-axis, you’re going to need that negative sign. Don't let the math choose for you; check your quadrants.

How to Convert From Sin to Cos in Code

If you're writing Python, C++, or JavaScript, you aren't doing this for fun. You're doing it because your library expects one and you have the other.

In most languages, the math libraries (like Python’s math or JS Math) take radians. If you have an angle a, and you want to switch from sin(a) to its cos equivalent using the shift method:

cos_val = math.cos((math.pi / 2) - a)

✨ Don't miss: The Race Between Education and Technology: Why We Are Still Losing

But honestly? Most developers just use the Pythagorean method if they already have the sine result stored in a variable. It’s often faster than re-calculating a trig function, which can be "expensive" for a processor if you're doing it ten thousand times a second in a rendering loop.

Real World Nuance: The Taylor Series and Approximation

Engineers at places like NASA or Boeing don't always use these "perfect" identities in high-speed hardware. Sometimes they use approximations.

The Taylor series allows us to represent sine and cosine as infinite sums.

$$\sin(x) = x - \frac{x^3}{3!} + \frac{x^5}{5!} - \dots$$

$$\cos(x) = 1 - \frac{x^2}{2!} + \frac{x^4}{4!} - \dots$$

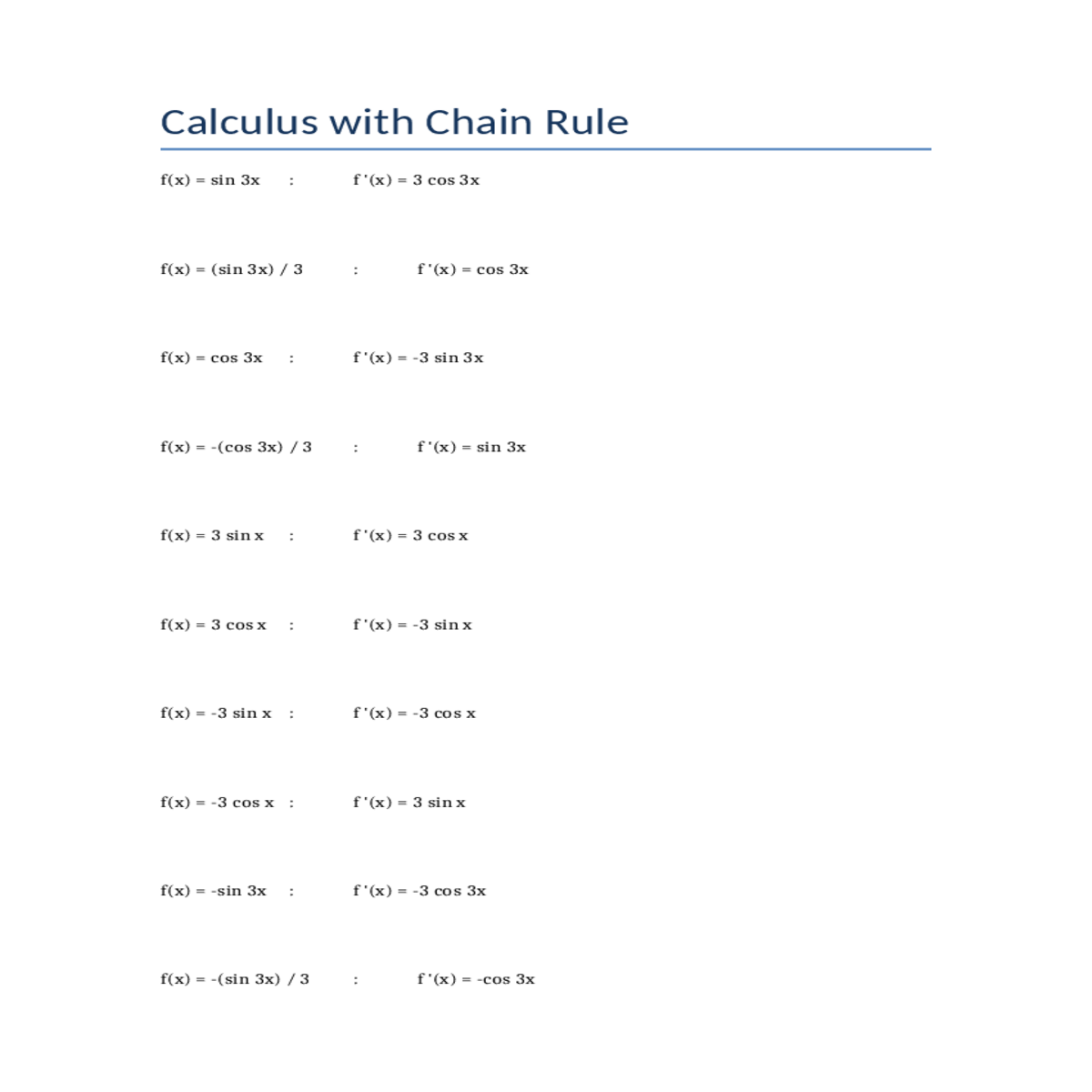

When you look at these, you can see how they relate. If you take the derivative of the sine series, you get the cosine series. This is why in calculus, the derivative of $\sin(x)$ is $\cos(x)$. If you're wondering how to convert from sin to cos in the context of change or motion, calculus is the bridge.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

- The 90-degree trap. People forget that $\sin(10^\circ)$ isn't $\cos(10^\circ - 90^\circ)$. It's $\cos(90^\circ - 10^\circ)$. Order matters.

- Calculator Mode. If you're using the identity $\sin(\theta) = \cos(90 - \theta)$ but your calculator is in Radians mode, you're going to get a nonsense answer. 90 in radians is about $1.57$. If you put $90$ into a radian calculation, you're spinning around the circle about $14$ times.

- The "Square Root" Blindness. As mentioned before, $\sqrt{0.25}$ is both $0.5$ and $-0.5$. If your angle is $150^\circ$, your sine is positive but your cosine must be negative.

Actionable Steps for Conversion

If you're stuck on a problem right now, follow this logic flow:

- Do you know the angle? Use the cofunction identity. Subtract your angle from $90^\circ$ (or $\pi/2$) and take the cosine of that new number.

- Do you only have the sine value (like 0.8)? Square it, subtract it from $1$, and take the square root.

- Are you in Quadrant II or III? Make your cosine result negative.

- Are you in Quadrant I or IV? Keep your cosine result positive.

For those working in digital signal processing or advanced wave mechanics, remember that "converting" is often just a matter of adjusting the starting point. A cosine wave is just a sine wave that had a head start. Use that intuition when you're looking at phase offsets in a DAW or an oscilloscope.

Stop trying to memorize every single identity in the back of the textbook. Focus on the unit circle. If you can visualize that circle, you don't need to memorize how to convert from sin to cos—you can just see it. The sine is the height; the cosine is the width. Everything else is just a way to describe that relationship.