You’ve probably seen those old family portraits tucked away in a shoebox—grainy, sepia-toned, or starkly monochromatic. There is something haunting about them. But let’s be real. Sometimes you just want to see what color your grandmother’s eyes actually were or if that 1940s car was cherry red or just a muddy brown.

The truth is that learning how to colorize a black and white photo used to be a dark art reserved for master retouchers in Hollywood or high-end archival labs. It took hours of manual masking. Now? We have AI that can do it in three seconds. But there is a massive catch. Most people hit a button, get a weirdly orange-skinned result, and call it a day. That’s not colorization; that’s a filter. If you want a photo that actually feels alive, you have to understand the interplay between light physics and digital tools.

🔗 Read more: How to Unsubscribe Instagram Subscriptions and Stop Those Random Charges

The AI Shortcut: Why It’s Usually Just "Okay"

Modern tools like Adobe Photoshop’s Neural Filters or standalone sites like Palette.fm use deep learning. They’ve looked at millions of color photos to guess what a tree or a sky should look like. It’s basically magic.

But AI is notoriously bad at historical context. It doesn't know that a specific military uniform in 1914 had a very particular shade of "horizon blue" that wasn't quite grey but wasn't quite sky blue either. It just sees a coat and guesses. If you are working on a historical project, relying solely on an algorithm is a recipe for inaccuracy. These tools often struggle with "color bleed," where the green of a background forest spills onto the edges of a person’s hair. It looks sloppy.

If you’re just messing around, the AI filter in Photoshop is fine. You go to Filter > Neural Filters > Colorize. Boom. Done. But if you want professional results, you’re going to use that AI layer as a "base" and then paint over it manually.

Understanding the Physics of Skin Tones

Skin isn't one color. This is the biggest mistake beginners make.

When you look at a human face, you’re seeing blood vessels, bone structure, and different levels of melanin. A realistic colorization requires at least three different zones. The forehead tends to be yellower. The cheeks, nose, and ears are redder because of increased blood flow. The jawline, especially on men, often has a cool, bluish or greenish tint due to hair follicles.

💡 You might also like: Username in a Sentence: Why You Keep Getting It Wrong

If you just slap a single "flesh" tone over a face, it looks like a plastic doll. You have to use "Soft Light" or "Color" blending modes in your software to layer these subtle shifts. This is what experts call "zoning." It’s tedious. It’s also the difference between a photo that looks like a memory and one that looks like a cartoon.

The Tools You Actually Need

Forget the "free online colorizers" that bombard you with ads. They compress your image and strip the metadata.

- Adobe Photoshop: Still the industry standard. The ability to use adjustment layers and masks is non-negotiable for high-end work.

- GIMP: The free alternative. It’s clunky. The interface feels like it’s from 2004, but it has the same layering logic as Photoshop.

- DeOldify: This is an open-source project by Jason Antic. It’s arguably the most sophisticated AI colorizer out there. If you’re tech-savvy, you can run it via Google Colab. It handles textures much better than the built-in Adobe filters.

A Step-by-Step Reality Check

First, you need a high-resolution scan. If you take a blurry cell phone picture of a physical photo, the colorization will look like garbage. Scan it at at least 600 DPI.

Next, fix the contrast. A black and white photo with "crushed" blacks—where all the shadow detail is just a solid block of ink—won't take color well. You need a full range of tones from pure white to deep black. Use a "Levels" or "Curves" adjustment to balance the image before you even think about color.

The Manual Layering Technique

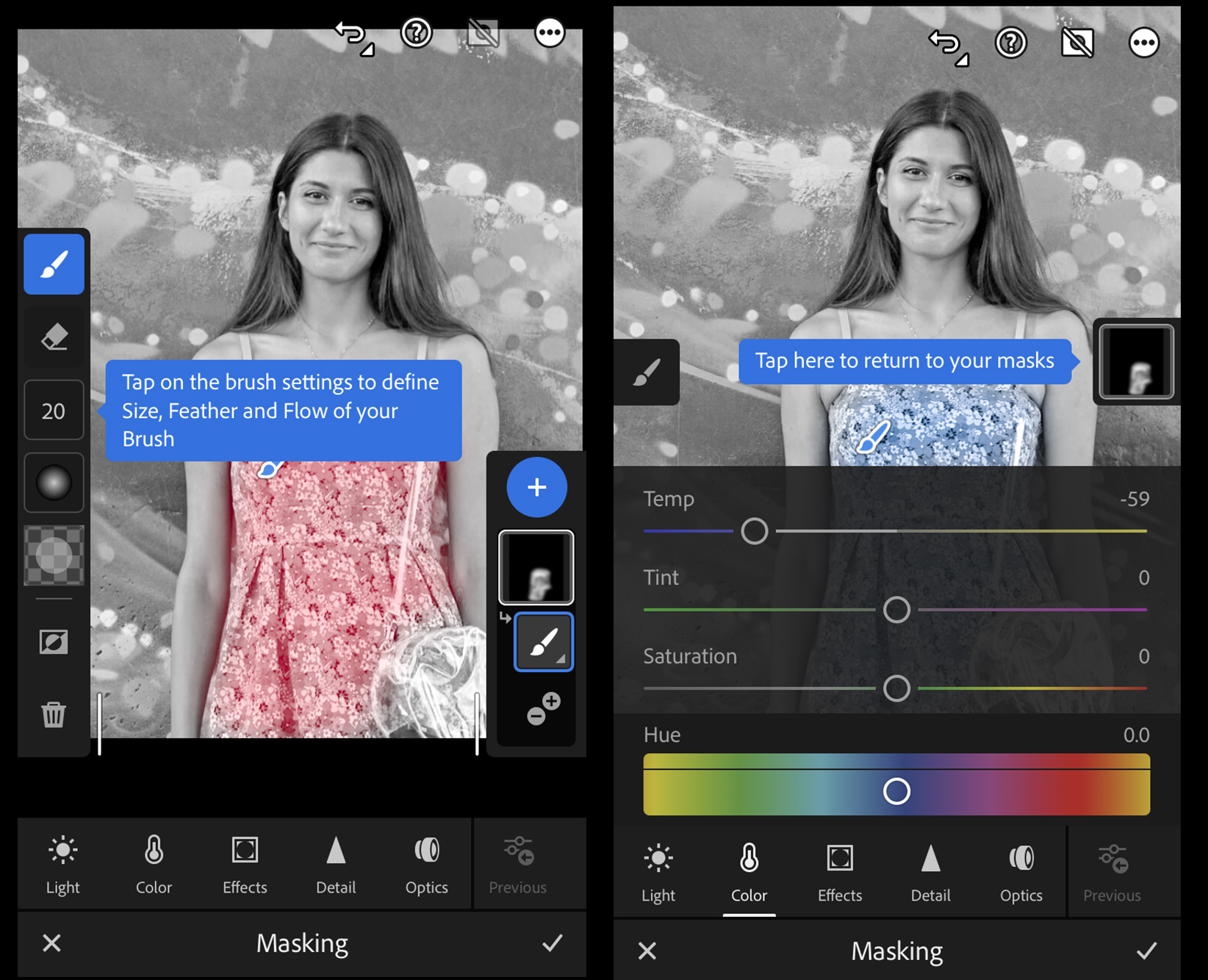

Once your "base" color is set by the AI, create a new layer. Set the blending mode to "Color." Pick a very low opacity brush—maybe 10%.

Start with the eyes. Did you know the whites of our eyes aren't actually white? They’re slightly blue or grey. Painting a tiny bit of cool tone into the eyes makes the person look human. Then, move to the clothing. Research the era. If the photo is from the 1920s, look up the popular dyes of the time. Synthetic dyes were different back then; colors were often more muted or had specific fades.

Why Historical Research Trumps Technology

I once saw a colorized photo of a Civil War soldier where the artist gave him a bright neon-blue uniform. It looked ridiculous.

The American Civil War "Union Blue" was a deep indigo, almost black in certain lights. If you are serious about how to colorize a black and white photo, you spend half your time on Google Images or in digital archives. You look for "extant garments." This is the term historians use for clothing that has survived from that time period.

- Check the medals.

- Check the vegetation (is that a Mediterranean olive tree or an English oak?).

- Look at the architecture.

If the bricks in the background are from a specific region in London, they shouldn't be bright American red; they should probably be a London Stock yellow-grey. Details matter. They provide the "weight" that makes the viewer believe the image is real.

The Ethics of Changing History

There is a massive debate about this in the museum world. Some archivists hate colorization. They argue it’s a "lie" because we are guessing. They feel it disrespects the original photographer's intent.

On the flip side, proponents like Marina Amaral—who is basically the rockstar of this field—argue that people didn't live in a black and white world. Colorizing these images makes the people in them feel like us. It bridges a gap of empathy that black and white photography sometimes creates.

The middle ground? Always keep the original. Colorization is an interpretation, not a replacement. Think of it like a performance of a classic play. It’s one way of seeing it, but the script remains the same.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

Watch out for the "Glow." When you colorize, it’s easy to let the color spill over the edges of an object into the background. This creates a weird halo effect. To fix this, you have to be precise with your masking. Zoom in 400%.

Another one: over-saturation. Old photos were often taken in natural light with film that had specific grain structures. If you make the colors too vibrant, they won't "sit" in the grain properly. You have to match the saturation to the noise level of the photo. If it’s a grainy photo, the colors should be a bit flatter.

Practical Steps to Get Started Right Now

Stop looking for a "one-click" solution. It doesn't exist for high-quality work.

💡 You might also like: Why the Google Meet Application Mac Version is Still Kinda Confusing

Start by downloading a high-res public domain image from the Library of Congress. Pick something simple—a portrait, not a busy street scene.

Run it through a basic AI colorizer to see what it suggests. Then, open that result in an editor and start desaturating the areas that look "neon." Add some red to the knuckles, some blue to the shadows under the eyes, and maybe a bit of yellow to the highlights of the hair.

Experiment with "Gradient Maps." This is a pro-level Photoshop trick where you map specific colors to specific brightness levels. It’s much faster than painting every pixel and usually results in a more cohesive look across the whole image.

The goal isn't just to add color. The goal is to restore the feeling of a moment that was once very, very real.

Actionable Next Steps

- Scan your originals at 600 DPI or higher to capture the silver halide grain structure properly.

- Use DeOldify or Photoshop’s Neural Filters as a 50% foundation, never as the finished product.

- Apply a "Color" blending mode layer for manual touch-ups on skin zones (yellow for forehead, red for cheeks/nose, blue/grey for jawline).

- Match color saturation to the photo's grain level to avoid a "cut-and-paste" look.

- Cross-reference historical archives for accurate uniform, vehicle, and architectural colors before committing to a palette.