You've probably been there. You find the perfect photo for your website or a print project, but it’s the size of a postage stamp. You try to blow it up, and suddenly, your crisp image looks like a Minecraft character lost in a fog bank. It’s frustrating. People think they can just "enhance" like they do in those cheesy police procedurals from the early 2000s.

Reality is a bit meaner.

When you change resolution of image files, you're essentially renegotiating the contract between pixels and physical space. Pixels aren't ink. They’re data points. If you don't have enough data points, your computer starts guessing. And honestly? Computers are mediocre guessers unless you give them the right tools and math to work with.

📖 Related: Finding the RAM in Linux: Why Most Users Look in the Wrong Place

Why Pixels per Inch Actually Matters (And Why It Doesn't)

Most people get hung up on the "300 DPI" rule. They hear it’s the holy grail of printing. While true for a physical magazine, DPI (Dots Per Inch) is technically a printer setting, whereas PPI (Pixels Per Inch) is what you're dealing with on your screen.

If you have a 1000x1000 pixel image, it has a million pixels. Period. If you set that to 72 PPI, it’s a big, low-density image. If you change it to 300 PPI without "resampling," the image stays exactly 1000x1000 pixels; it just tells the printer to pack those pixels tighter. The image gets smaller on paper, but sharper.

But what if you need it to stay big? That’s where things get tricky.

Upsampling is the process of adding pixels that weren't there before. Your software looks at Pixel A (blue) and Pixel B (white) and decides that the new Pixel C in the middle should probably be light blue. This is called interpolation. Linear interpolation is the old-school way—it's fast but usually makes things look blurry or "soft."

The Tools You’re Actually Going to Use

If you’re on a Mac, Preview is surprisingly decent for quick changes. You go to Tools > Adjust Size. Just make sure "Resample Image" is checked if you actually want to change the pixel count. If you uncheck it, you're just changing the metadata, which is basically useless for web uploads.

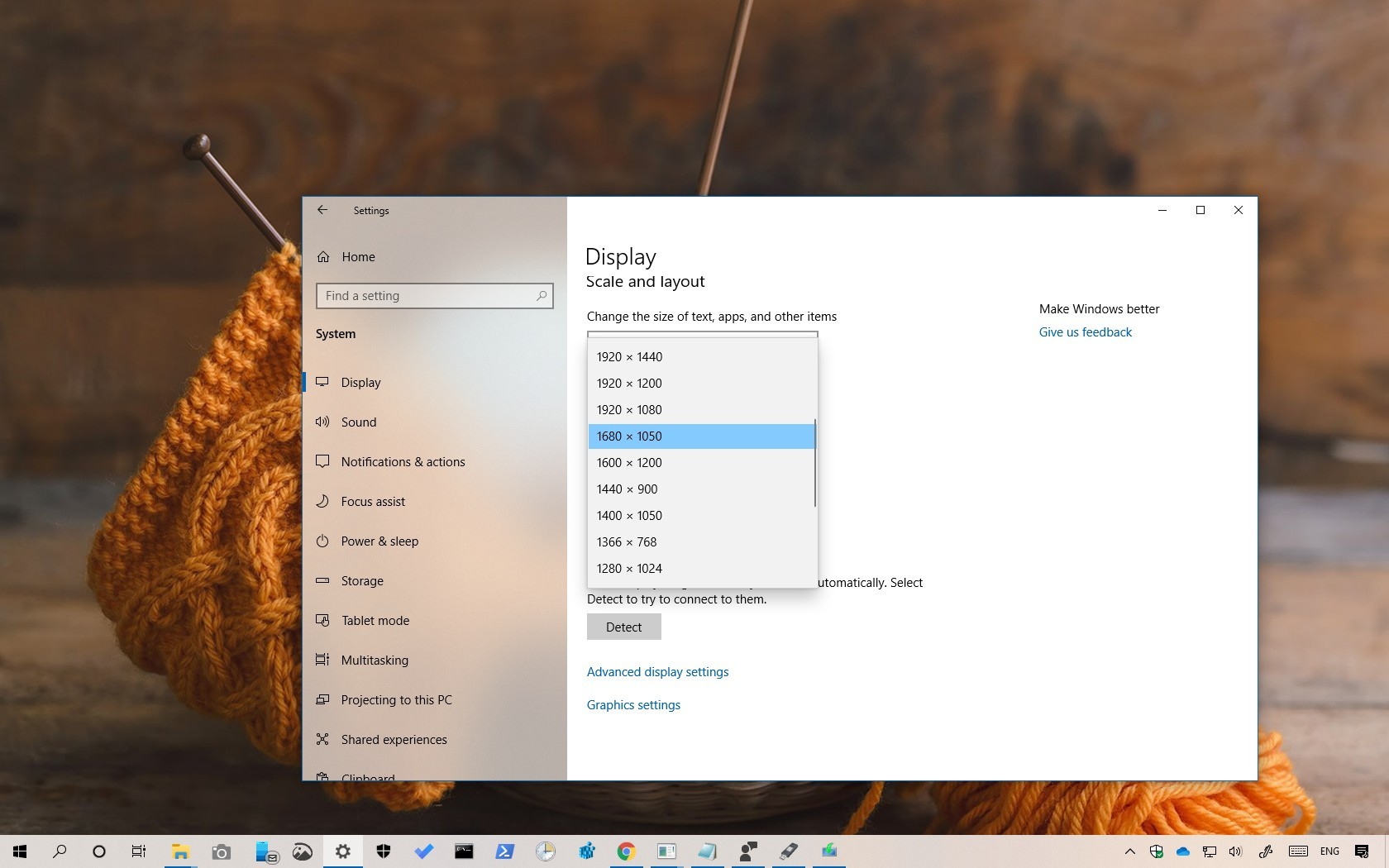

Windows users usually gravitate toward Photos or Paint 3D, but let's be real: they aren't great for high-quality scaling.

Adobe Photoshop remains the industry standard for a reason. Its "Preserve Details 2.0" algorithm is a beast. It uses a bit of machine learning to identify textures—like hair or skin—and tries to keep them from turning into mush. To find it, you head to Image > Image Size, and in the "Resample" dropdown, you pick the one that fits your goal.

The AI Revolution in Upscaling

Honestly, the traditional methods are dying.

Companies like Topaz Labs with their Gigapixel AI or Adobe with Super Resolution have changed the game. They don't just guess what the middle pixel should be based on its neighbors. They’ve "seen" millions of photos. They know what a brick wall is supposed to look like. When you change resolution of image assets using these tools, the software reconstructs the details.

It’s almost like magic, but it’s really just heavy-duty pattern recognition.

I’ve seen Gigapixel take a grainy 640x480 photo from a 2005 flip phone and turn it into something you could actually print on a canvas. It’s not perfect—sometimes it creates weird artifacts that look like "swirls" or plastic skin—but it's miles ahead of the old Bicubic Smoother method.

Common Myths About High Resolution

One big lie is that "more is always better."

🔗 Read more: Is Apple Open on Thanksgiving? What Most People Get Wrong

If you’re uploading a photo to Instagram, and you upload a massive 8000-pixel-wide file at 300 PPI, Instagram’s compression algorithm is going to absolutely shred it. It’ll look worse than if you’d just uploaded a clean 1080-pixel-wide version.

Then there’s the file format trap.

- JPEGs are "lossy." Every time you save a JPEG after changing the resolution, you lose a little bit of soul. The "artifacts" (those weird blocks around edges) get worse.

- PNGs are "lossless." They’re better for graphics with sharp edges, but the files get huge very fast.

- TIFFs are the heavyweights. If you’re a photographer sending work to a gallery, you use TIFF.

You also have to consider the viewing distance. This is a nuance most beginners miss. A billboard on the highway might only be 15 or 20 PPI. Why? Because you're looking at it from 100 feet away. Your eyes do the "resampling" for you. You only need 300 PPI when the paper is six inches from your face.

Technical Step-by-Step for Sharp Results

If you want to do this right without buying fancy software, follow a "step-up" approach.

Instead of jumping from 100% size to 400% in one go, some old-school editors swear by increasing the size in 10% increments. This is less relevant now with modern algorithms, but it’s a fun trick if you’re stuck using basic software.

- Open your file in your editor of choice.

- Duplicate the layer. Never work on the original. Ever.

- Navigate to your "Image Size" or "Canvas" settings.

- Switch the units from "inches" to "pixels." It’s much easier to keep track of what’s actually happening.

- If you're using Photoshop, select Preserve Details 2.0.

- Add a tiny bit of "Unsharp Mask" or "Smart Sharpen" after the resize.

When you enlarge an image, the edges naturally soften. A little bit of sharpening—just a touch—helps trick the eye into seeing detail that was technically lost during the stretch.

Don't Forget the Aspect Ratio

This is where people mess up their Facebook profile pictures.

If you change resolution of image dimensions but don't "Constrain Proportions" (usually represented by a little chain-link icon), you’re going to end up with a "stretched" look. People look wider, buildings look skewed. Always keep that link active unless you intentionally want to distort the image.

When Should You Just Give Up?

You can’t fix a blur.

📖 Related: Finding the Right Cable for Vizio TV: What Most People Get Wrong

If the original photo is out of focus or has heavy motion blur, increasing the resolution just gives you a high-resolution version of a blurry mess. AI can sharpen things a bit, but it can't fix a lens that wasn't focused correctly.

Also, watch out for "noise."

When you scale up a photo taken in a dark room, the digital noise (those colored grains) gets scaled up too. Suddenly, those tiny dots become big, ugly blotches. You’ll need to run a noise reduction pass before you increase the resolution. If you do it after, the noise becomes part of the image structure, and it’s a nightmare to remove.

The Future of Resizing

We’re moving toward a world where "resolution" is becoming an abstract concept.

Vector graphics (like SVGs) already solved this for logos—they use math instead of pixels, so they can be the size of a planet without losing quality. For photos, we’re seeing "neural filters" that can literally change the direction someone is looking or add more grass to a field.

Changing the resolution is no longer just about making things bigger; it’s about generative reconstruction.

Practical Steps to Take Now

To get the best results when you need to upscale today, follow this workflow:

- Assess the source: If it's a screenshot, it's already low quality. Expect limits.

- Use the right tool: Use Waifu2x (it's free and open-source) for illustrations or anime-style art. Use Adobe Lightroom’s Super Resolution for raw photos.

- Check your output: Always zoom in to 100% (Actual Pixels) after you resize. If it looks "waxy," you pushed it too far.

- Save a Master Copy: Always keep your original file. Export your high-res version as a new file so you can go back if the client or the printer hates the result.

- Test Print: If this is for physical media, print a small "crop" of the high-res version on your home printer first. It saves money and heartbreak.

The math behind these images is complex, but the execution doesn't have to be. Just remember that you're trying to create something out of nothing. Treat the pixels with a bit of respect, don't over-sharpen, and always prioritize the "cleanliness" of the image over the raw size.