You're standing at your front door. You walk ten miles north, turn around, and walk ten miles back. To your fitness tracker, you’re a hero. You just crushed a twenty-mile hike. But to a physicist? You haven’t moved an inch. Honestly, it’s a little insulting.

That’s the core quirk of physics. It doesn't care about your effort or the sweat you poured into those miles. It only cares about where you started and where you ended up. This is the fundamental difference between distance and displacement. Distance is the total ground you covered; displacement is the straight-line gap between your "before" and "after" photos. If you want to know how do you calculate displacement, you have to stop thinking about the path and start thinking about the vector.

The Vector Secret: Why Direction Changes Everything

Most people mess this up because they treat displacement like a regular number. It’s not. In the world of math, we call it a vector quantity. This just means it has two parts: how far and which way.

If I tell you to walk five meters, you’re going to ask, "In what direction?" That’s displacement. If I just say "run five meters," that’s distance. When you’re trying to figure out how do you calculate displacement, you’re looking for that change in position, often represented by the Greek letter delta ($\Delta x$).

The simplest formula you’ll ever see in a physics textbook is:

$$\Delta x = x_f - x_i$$

Here, $x_f$ is your final position and $x_i$ is where you began. Simple, right? If you start at mile marker 10 on a highway and end at mile marker 50, your displacement is 40 miles east (or whatever direction the numbers increase). If you go from 50 back to 10, your displacement is -40 miles. That negative sign is crucial. It tells you the direction is reversed.

✨ Don't miss: Finding a mac os x 10.11 el capitan download that actually works in 2026

When the Path Gets Messy: 2D Displacement

Life rarely happens in a straight line. You’re usually turning corners, dodging traffic, or navigating a city grid. This is where the Pythagorean theorem—that thing you probably thought you’d never use after tenth grade—becomes your best friend.

Imagine you walk 3 miles North and then 4 miles East. Your total distance is 7 miles. Easy. But your displacement? You've basically drawn two sides of a right triangle. To find the "shortcut" across that triangle, you use:

$$c^2 = a^2 + b^2$$

Or, more specifically for our needs:

$$d = \sqrt{x^2 + y^2}$$

In our 3-north, 4-east example, that’s $\sqrt{3^2 + 4^2}$, which is $\sqrt{9 + 16}$. The square root of 25 is 5. So, your displacement is exactly 5 miles at a northeast angle. You’ve moved 5 miles away from your origin, even though your feet felt all 7 miles of that walk.

The Velocity Connection

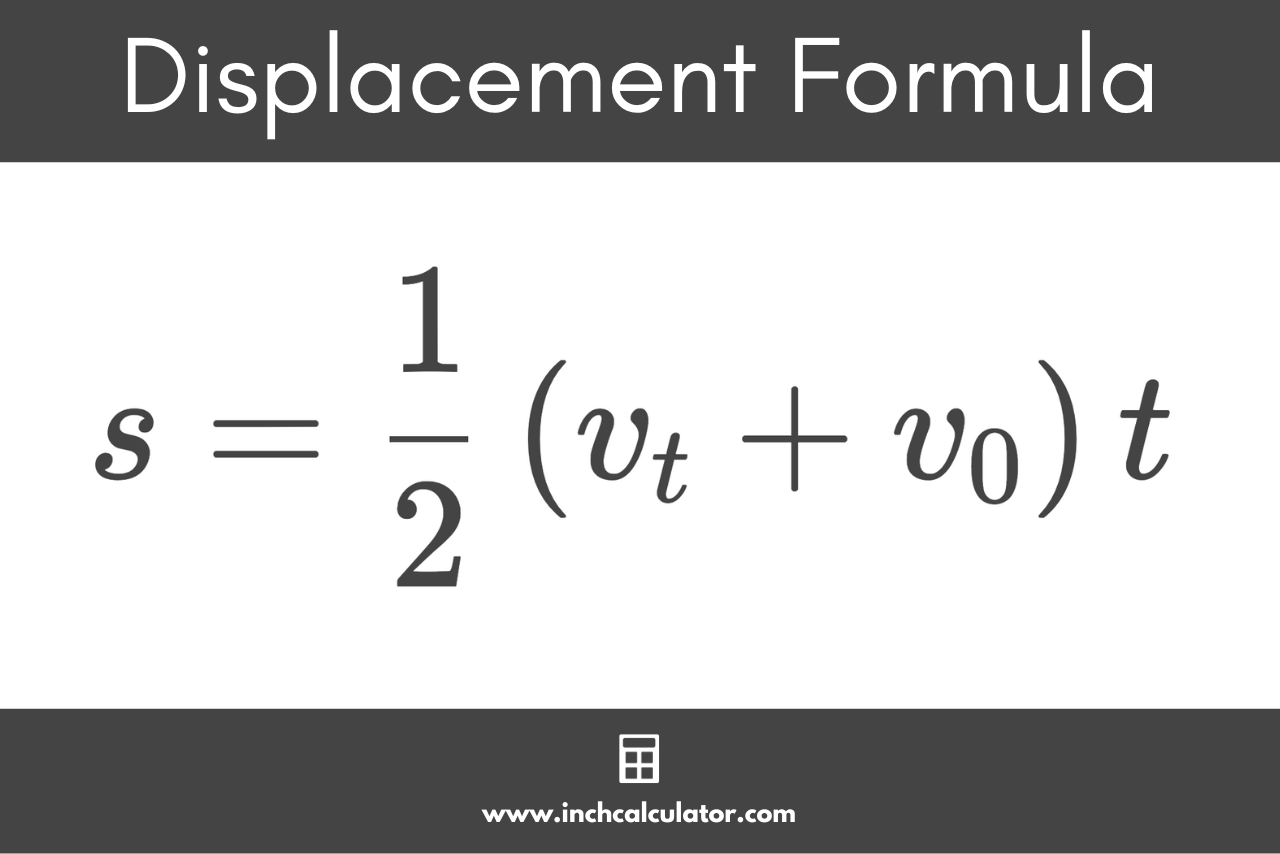

Sometimes you don’t know the start and end points. Maybe you only know how fast you were going and for how long. If you’re traveling at a constant velocity, you can find your displacement by multiplying your velocity by time.

Wait.

🔗 Read more: Examples of an Apple ID: What Most People Get Wrong

Don't confuse velocity with speed. Speed is "60 mph." Velocity is "60 mph North." If a car drives in a perfect circle at 60 mph for an hour, its average speed is 60 mph. Its average velocity? Zero. Because it ended exactly where it started.

When you have constant acceleration—like a ball rolling down a ramp or a car flooring it at a green light—the math gets slightly more intense. You use what physicists call the kinematic equations. The most common one for displacement looks like this:

$$\Delta x = v_it + \frac{1}{2}at^2$$

Basically, you take your initial velocity ($v_i$) times time ($t$), then add half of your acceleration ($a$) times time squared ($t^2$). It looks intimidating on a whiteboard, but it’s just a way to account for the fact that you’re speeding up as you go.

Real-World Nuance: Why This Actually Matters

In the real world, engineers use these calculations for everything from GPS calibration to autonomous vehicle programming. If a self-driving car only tracked distance, it would get lost the moment it made a U-turn. It needs to know its displacement relative to its home base to navigate accurately.

Think about aviation. A pilot flying from New York to London has to account for the curvature of the Earth. On a flat map, displacement looks like a straight line. On a globe, that "straight line" is actually a curve called a Great Circle. If the pilot just calculated linear displacement without accounting for the Earth's radius, they’d end up hundreds of miles off course.

💡 You might also like: AR-15: What Most People Get Wrong About What AR Stands For

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Forgetting the sign: In one-dimensional problems, a negative sign IS the direction. Dropping it is like saying "I'm 5 miles away" when you should have said "I'm 5 miles behind you."

- Mixing units: Never try to calculate displacement using meters for distance and kilometers per hour for velocity. Convert everything to SI units (meters, seconds, kilograms) before you touch a calculator.

- Round-trip confusion: If the start and end points are the same, displacement is always zero. Always. It doesn't matter if you traveled to Mars and back.

Mastering the Calculation

If you’re staring at a physics problem or trying to map out a project, follow this mental checklist:

- Identify the starting coordinate ($x_i$).

- Identify the final coordinate ($x_f$).

- Subtract the start from the finish.

- If it's two-dimensional, treat the x-axis and y-axis separately, then combine them using the Pythagorean theorem.

- Always attach a direction (North, 45 degrees, or just a +/- sign).

Actionable Steps for Accurate Results

Start by sketching a coordinate plane. Seriously. Even pros do this. Draw an arrow from the origin to your starting point, then an arrow to your end point. The vector connecting those two arrowheads is your displacement.

If you are dealing with complex movement, break the path into individual vectors. Use a calculator that handles trigonometric functions if you need to find the specific angle ($\theta$) of your displacement using $\tan^{-1}(y/x)$.

For those using data from sensors or GPS, ensure you are sampling at a high enough frequency. Displacement calculated from "velocity x time" is only as accurate as your measurement of time. If your clock drifts, your calculated position drifts with it. Check your sensors against a known fixed point—a process called "zeroing"—to ensure your $x_i$ is actually where you think it is.