Let's be real. Statistics can feel like a dry, dusty attic of a subject that nobody actually wants to visit unless they’re forced to by a thesis advisor or a boss who’s obsessed with "data-driven insights." But then you hit a wall where you actually need to know if the patterns you're seeing in your data are real or just a weird coincidence. That’s usually when you realize you need to figure out how to calculate chi square. It sounds intimidating, like some ancient Greek ritual, but it’s basically just a way to measure the gap between what you expected to happen and what actually went down.

You’ve probably seen those political polls or medical studies where they talk about "statistical significance." They aren't just guessing. They are using tests like the Pearson Chi-Square to see if the relationship between two things is just a fluke. Think about it. If you flip a coin 100 times and get 52 heads, you don’t panic. But if you get 90 heads? Something is up with that coin. The chi-square test is the math that tells you exactly how "up" it is.

The Basic Logic: It’s All About Disappointment

At its core, calculating chi-square is about measuring disappointment. You have a theory (the "Expected" value) and you have reality (the "Observed" value). The chi-square statistic is just the sum of all those little disappointments, squared and normalized so we can actually compare them.

👉 See also: 404 Phone Number Lookup: Why You Keep Getting Dead Ends and How to Actually Find Who Called

The formula looks like this:

$$\chi^2 = \sum \frac{(O_i - E_i)^2}{E_i}$$

Don’t let the Greek letters scare you. $\chi^2$ is just the symbol for Chi-Square. That big $E$ thing is a sigma, which just means "add everything up." $O$ is what you saw, and $E$ is what you thought you’d see.

Picking Your Poison: Goodness of Fit vs. Independence

Before you start crunching numbers, you have to know which version of the test you're running. Honestly, this is where most people trip up.

There's the Goodness of Fit test. Use this when you have one variable and you want to see if it matches a specific distribution. Like, if you buy a bag of M&Ms and want to see if the color distribution matches what the factory claims. You’re comparing your one bag against a known standard.

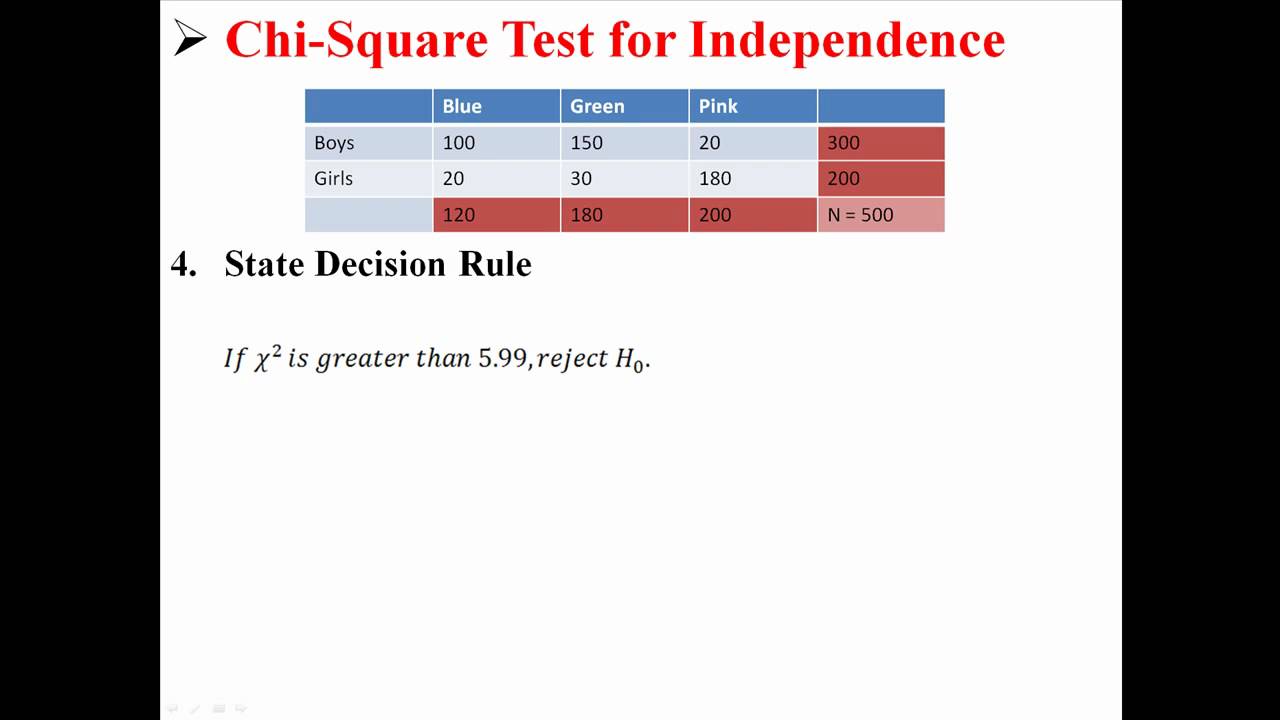

Then there’s the Test of Independence. This is the big one. This is what you use when you have two variables—say, "Gender" and "Voting Preference"—and you want to know if they are related. Does being a woman make you more likely to vote for a specific candidate? Or are those two things totally unrelated? This test uses a contingency table, which is just a fancy way of saying a grid.

A Real-World Walkthrough: The Coffee Shop Dilemma

Let’s use an illustrative example. Imagine you own a small coffee shop called "The Daily Grind." You’ve noticed that people seem to order more oat milk lattes on rainy days. You want to know if this is a real trend or if you’re just imagining things. To figure this out, you’re going to calculate chi square.

You track 200 customers over a week.

Step 1: Set Up Your Null Hypothesis

In stats-speak, we start with the "Null Hypothesis" ($H_0$). This is the boring version of reality where nothing interesting is happening. In our case, $H_0$ is: "Milk choice and weather are completely independent." Basically, the rain doesn't change what people drink.

Step 2: Build Your Observed Table

You look at your receipts. Here is what actually happened:

- On Sunny Days: 80 people ordered Dairy, 20 ordered Oat.

- On Rainy Days: 40 people ordered Dairy, 60 ordered Oat.

Total customers: 200. Total Sunny: 100. Total Rainy: 100. Total Dairy: 120. Total Oat: 80.

Step 3: Calculate the "Expected" Values

This is the part that feels like a bit of a chore. If there was no relationship between weather and milk (our Null Hypothesis), we’d expect the proportions to be the same across the board.

To find the expected value for any cell in your grid, you use this trick:

(Row Total * Column Total) / Grand Total.

For Sunny/Dairy: (100 * 120) / 200 = 60.

For Sunny/Oat: (100 * 80) / 200 = 40.

For Rainy/Dairy: (100 * 120) / 200 = 60.

For Rainy/Oat: (100 * 80) / 200 = 40.

Now you have two tables. One is reality. One is the "boring" version of reality.

Step 4: Use the Formula

Now we apply $\frac{(O - E)^2}{E}$ to every single cell.

- Sunny/Dairy: $(80 - 60)^2 / 60 = 400 / 60 = 6.67$

- Sunny/Oat: $(20 - 40)^2 / 40 = 400 / 40 = 10.0$

- Rainy/Dairy: $(40 - 60)^2 / 60 = 400 / 60 = 6.67$

- Rainy/Oat: $(60 - 40)^2 / 40 = 400 / 40 = 10.0$

Step 5: Add Them Up

$6.67 + 10.0 + 6.67 + 10.0 = 33.34$

Your Chi-Square statistic is 33.34.

What Does That Number Even Mean?

A 33.34 sounds big, right? But in statistics, "big" depends on your "Degrees of Freedom" ($df$). For a contingency table, $df$ is $(Rows - 1) * (Columns - 1)$.

We have 2 rows (Sunny/Rainy) and 2 columns (Dairy/Oat).

$(2-1) * (2-1) = 1$.

So, $df = 1$.

Now you look at a Chi-Square Distribution Table. You can find these in the back of any old textbook or just Google one. For 1 degree of freedom, the "critical value" at a 0.05 significance level (the standard 95% confidence rule) is 3.84.

Since our 33.34 is way, way higher than 3.84, we reject the Null Hypothesis. You aren't crazy. People definitely want more oat milk when it’s raining.

The P-Value Trap

I’ve seen a lot of people get obsessed with the p-value. It’s the probability that your results happened by pure chance. If your p-value is less than 0.05, you’ve got something. But remember, a low p-value doesn't mean the effect is huge. It just means it's real. In our coffee shop, the effect is both real and pretty massive.

There are some rules you can't break when you calculate chi square. If you do, the math falls apart. Karl Pearson, the guy who basically invented this in 1900, was pretty clear about the assumptions. First, your data has to be "categorical." You can't use chi-square for heights or weights unless you group them into buckets (like "Tall" and "Short"). Second, the observations must be independent. You can't count the same person twice.

📖 Related: Why Every Blue Origin Rocket Launch Actually Matters for the Rest of Us

Finally—and this is the one that kills most student projects—your expected frequency in any cell should usually be 5 or more. If you have a tiny sample size, the chi-square test gets twitchy and unreliable. If you're dealing with really small numbers, you might need to look into Fisher's Exact Test instead.

Nuance Matters: Why Sample Size Is a Double-Edged Sword

Here is something weird. If you have a massive sample size—say, 100,000 people—almost everything becomes "statistically significant." A tiny, meaningless difference between two groups will trigger a high chi-square value just because the sample is so huge. This is why you should always look at "effect size" (like Cramer's V) alongside your chi-square.

It prevents you from making a big deal out of a tiny ripple in the water.

Practical Steps to Master the Math

If you're ready to do this yourself, don't do it by hand unless you're in a classroom. It’s 2026. Use the tools.

- Excel/Google Sheets: Use the

=CHISQ.TEST(actual_range, expected_range)function. It’s instant. - Python: Use

scipy.stats.chi2_contingency. It’s one line of code and handles the degrees of freedom for you. - Check your "Expected" counts: If any cell in your "Expected" table is less than 5, stop. Group your categories together or get more data.

- Interpret with caution: Correlation isn't causation. Just because oat milk sales go up when it rains doesn't mean the rain causes the craving. Maybe people who like oat milk just happen to be the same people who walk to the shop in the rain.

Calculating chi-square is a foundational skill. Whether you're in marketing, biology, or just trying to win an argument about board game luck, knowing how to separate signal from noise is basically a superpower. Start by building a simple 2x2 table of something you're curious about. Once you run the numbers a few times, the formula stops looking like Greek and starts looking like a map.

Go grab your data. Check those frequencies. See if your "expected" reality actually matches the world you're living in.