You've probably heard the "eat less, move more" mantra a thousand times. It's the standard advice. But honestly, if it were that simple, we’d all be walking around with six-packs and infinite energy. The math of weight loss is straightforward in theory but messy in practice because your body isn't a calculator; it's a complex survival machine that's actively trying to keep you from starving. To understand how to calculate calories deficit properly, you have to look past the apps and actually understand your metabolism.

It’s about more than just cutting out your evening snack.

The basic definition of a calorie deficit is simple: you burn more energy than you take in. When this happens, your body taps into its internal energy stores—usually body fat—to make up the difference. Sounds easy, right? Well, the "how" is where most people trip up. They go too low, too fast, and end up crashing within a week.

The Foundation: Finding Your Maintenance Level

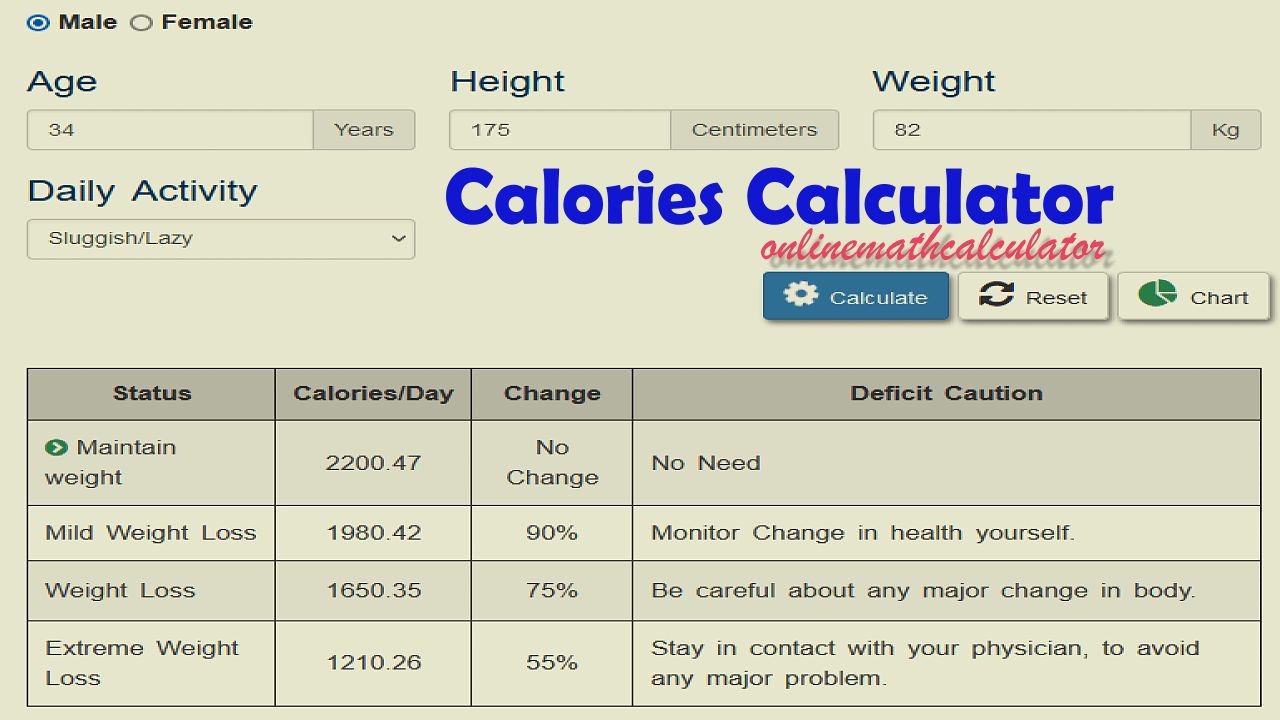

Before you can subtract anything, you need to know your starting point. This is your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). Think of it as your "break-even" number. If you eat this amount, you stay exactly the same weight. No changes. No drama.

Most people start by using the Mifflin-St Jeor equation. It’s widely considered the most accurate formula for non-obese individuals in clinical settings.

The formula for men is:

$$10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} + 5$$

For women, it looks like this:

$$10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} - 161$$

This gives you your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR). That’s the energy you burn just existing—lying in bed, breathing, thinking. But you don't just lie in bed. You walk to the car. You lift groceries. You fidget during Zoom calls.

Factoring in your movement

To get your actual TDEE, you multiply that BMR by an activity factor. This is where everyone messes up. We all tend to overestimate how hard we work out. If you go to the gym three times a week for 45 minutes but sit at a desk for the other 23 hours of the day, you aren't "highly active." You're sedentary with a side of exercise.

- Sedentary (office job, little exercise): BMR x 1.2

- Lightly active (light exercise 1-3 days/week): BMR x 1.375

- Moderately active (moderate exercise 3-5 days/week): BMR x 1.55

- Very active (hard exercise 6-7 days/week): BMR x 1.725

Be honest here. If you lie to the formula, the formula lies to you.

How to Calculate Calories Deficit for Sustainable Results

Once you have that TDEE number, you need to decide how much to cut. The old-school rule was the "3,500 calorie rule." The idea was that one pound of fat equals 3,500 calories, so if you cut 500 calories a day, you'd lose exactly one pound a week.

It's a bit of a myth.

Research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), specifically work led by Dr. Kevin Hall, shows that the body adapts. As you lose weight, you burn fewer calories. Your "500 calorie deficit" today might only be a "200 calorie deficit" in three months because your body has become more efficient (or you've lost muscle).

The 20% Rule of Thumb

Instead of picking a random number like 500 or 1,000, try a percentage. A 15% to 25% reduction from your TDEE is usually the "sweet spot." It’s enough to see progress but not so much that you’re ready to eat your keyboard by 3:00 PM.

If your maintenance is 2,500 calories:

- A 20% deficit is 500 calories.

- Your goal is 2,000 calories.

If your maintenance is 1,800 calories:

- A 20% deficit is 360 calories.

- Your goal is 1,440 calories.

See the difference? A flat 500-calorie cut is way more aggressive for a smaller person than a larger one.

Why the Scale Lies to You

You’ve done the math. You’re hitting your numbers. But Monday morning rolls around, and the scale says you gained two pounds.

Don't panic.

Weight loss isn't linear. It's a jagged line that trends downward over months, not days. You might be in a perfect calorie deficit, but if you had a salty meal last night, your body is holding onto extra water. If you started a new lifting program, your muscles are likely inflamed and holding fluid to repair themselves. For women, menstrual cycles can cause weight swings of 3-5 pounds easily, completely masking fat loss for weeks at a time.

You have to look at weekly averages. Take your weight every morning, add it up at the end of the week, and divide by seven. If that average is moving down over a 3-week period, you're in a deficit. If it's not, you aren't. It's the most objective way to check your work.

The Role of Protein and NEAT

If you just cut calories without looking at what you're eating, you’ll probably lose muscle. This is a disaster for your metabolism. Muscle is metabolically expensive; it burns calories just sitting there. Fat doesn't.

To protect your muscle while in a deficit, you need protein. Most evidence-based nutritionists, like Dr. Eric Helms or those at the International Society of Sports Nutrition (ISSN), suggest 0.7 to 1 gram of protein per pound of body weight. It keeps you full and keeps your metabolism from nosediving.

Then there’s NEAT—Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis.

✨ Don't miss: What Is a Medical Directive? Why You Probably Need One Today

This is the stuff you don't count as "exercise." It’s pacing while you talk on the phone or taking the stairs. When you go into a calorie deficit, your body gets sneaky. It tries to save energy by making you move less. You might stop fidgeting or sit down more often without realizing it. This can "shrink" your deficit without you touching your food.

Monitoring your daily steps is actually a better way to ensure your deficit stays intact than tracking your heart rate during a treadmill session.

Tracking: The Good, The Bad, and The Annoying

You don't have to track every morsel of food for the rest of your life. But if you've never done it, you probably have no clue how many calories are in things. A tablespoon of peanut butter is supposed to be 16 grams. Have you ever actually weighed 16 grams of peanut butter? It’s tiny. Most people "glob" on 30-40 grams and call it a tablespoon.

That’s a 200-calorie mistake right there.

- Use a digital scale. Measuring cups are for liquids. For solids, they are incredibly inaccurate.

- Track the "hidden" stuff. The oil you put in the pan, the creamer in your coffee, the "taste test" of the pasta sauce. It all counts.

- Be honest about dining out. Restaurant meals are almost always 20-30% higher in calories than the menu says because chefs love butter.

When to Stop Calculating

Metabolic adaptation is real. If you stay in a deficit for too long—say, four or five months—your hormones (like leptin and thyroid hormones) start to shift. You get hungrier. You get colder. You get "diet brain."

This is why "diet breaks" or "maintenance phases" are vital.

Every 8-12 weeks, it’s a good idea to bring your calories back up to maintenance for a week or two. It doesn't "reset" your metabolism in a magical way, but it does lower your stress levels (cortisol) and helps normalize hunger hormones. It's a psychological breather that makes the next phase of the deficit actually work.

🔗 Read more: Images of poison ivy on skin: Why identifying the rash early saves you weeks of misery

Real-World Action Steps

- Determine your BMR using the Mifflin-St Jeor formula.

- Multiply by a conservative activity factor. When in doubt, pick the lower one.

- Subtract 15-20% to find your daily target.

- Prioritize protein to keep your muscle and stay full.

- Track your weight daily but only care about the weekly average.

- Move more throughout the day. Don't just rely on the gym; hit a step goal.

- Adjust after four weeks. If the scale average hasn't moved, drop your calories by another 100 or add 2,000 steps a day.

The math gives you the map, but your body provides the terrain. Listen to it. If you're constantly exhausted, losing hair, or can't sleep, your deficit is too aggressive. It’s a marathon, not a sprint. Take the slow road; it's the only one that actually leads to a permanent destination.