You just installed a fresh distro. Maybe it's Ubuntu, or maybe you're feeling brave with Arch. You try to run a simple update, and boom: "User is not in the sudoers file. This incident will be reported." Reported to who? Santa? The Linux police? It’s one of those classic "welcome to Linux" moments that feels like a slap in the face.

Honestly, the process to add linux user to sudo is actually dead simple once you realize there are two main ways to do it. One is the "quick and dirty" group method, and the other is the "surgical precision" method using the visudo command. Most people just want their user to work, so they go for the group change. But if you're managing a server or you actually care about security, you need to understand the nuances of the /etc/sudoers file.

The easiest way: Using the 'usermod' command

If you are on Ubuntu, Debian, or Linux Mint, there is a specific group called sudo. On Fedora, CentOS, or RHEL, that group is usually called wheel. It’s an old-school Unix term, named after the "big wheels" who ran the system.

To get this done, you need to be logged in as root or another user who already has sudo powers. Open your terminal. Type this:

sudo usermod -aG sudo yourusername

Wait.

Don't just copy-paste that. If you're on Fedora, change sudo to wheel. The -aG flag is the most important part here. The a stands for append, and the G stands for group. If you forget the a, you might accidentally kick yourself out of every other group you belong to, like the audio or docker groups. I've seen people do it. It’s a mess to fix.

Once you run that, nothing happens. No "Success!" message. That’s just the Linux way. You have to log out and log back in for the changes to take effect. If you're in a rush, you can run newgrp sudo to refresh the session in that specific terminal window, but a full logout is always cleaner.

Why 'visudo' is actually the better choice

Some people think editing the sudoers file is scary. It can be. If you mess up the syntax in /etc/sudoers using a regular text editor like Nano or Vim, you might find yourself locked out of your own system. It’s a nightmare scenario where you can't even fix the file because you no longer have the permission to edit it.

This is why visudo exists.

When you run sudo visudo, the system opens the configuration file in a safe mode. It won't let you save the file if you made a typo. It’s like a spell-checker for your system's most sensitive security file.

Inside that file, you'll see a line that looks something like this:root ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

If you want to add linux user to sudo manually, you can add a line right below that:username ALL=(ALL:ALL) ALL

Breaking down the sudoers syntax

It looks like gibberish, right? Let’s break it down so it actually makes sense. The first ALL means this rule applies to all hostnames. The first (ALL:ALL) means the user can run commands as any user or any group. The final ALL means they can run any command.

Sometimes you don't want to give someone total power. Maybe you have a junior dev who only needs to restart the Nginx service. You can limit them. You can be specific. You can be the gatekeeper.

For example, username ALL = NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/apt-get allows that user to run updates without even typing their password. It’s convenient, but it’s a security hole the size of a truck if that account gets compromised. Use it sparingly.

The 'wheel' group vs the 'sudo' group

Why the different names? It’s mostly historical baggage. Red Hat and its cousins stuck with the BSD-style wheel group. Debian-based systems went with sudo because it's more descriptive.

If you're jumping between systems, always check which one exists first by running grep -E '^sudo|^wheel' /etc/group. It’ll save you five minutes of scratching your head when the command fails.

Actually, there's a funny bit of history there. The "Wheel" group comes from the phrase "big wheel," referring to a person with great power or influence. In the 1980s, if you weren't in the wheel group on a PDP-10, you weren't doing much of anything.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

One thing that trips people up is the password requirement. By default, when you add linux user to sudo, they have to use their own password to run commands, not the root password. This is the whole point of sudo. It provides an audit trail. You can look at the logs in /var/log/auth.log and see exactly who ran rm -rf / and fire them accordingly.

If you find that your user still can't use sudo after adding them to the group, check the file permissions on the sudo binary. It should have the SUID bit set. Run ls -l /usr/bin/sudo. You should see an s in the permissions, like -rwsr-xr-x. If it’s not there, something is very wrong with your installation.

Handling the "Incident will be reported" mystery

We’ve all seen it. The ominous warning. Where does the report go? Usually, it just goes to a local mail file for the root user. On most modern desktops, it basically goes nowhere unless you've configured a mail server. It’s a relic of a more social era of computing where a System Administrator would actually read those logs every morning over coffee.

If you are that admin, you can check these reports by looking at /var/mail/root. Don't expect a thrilling read. It’s mostly just frustrated users typing their passwords wrong.

Advanced: Adding users without groups

What if you don't want to use groups at all? You can create a specific file for the user in the /etc/sudoers.d/ directory. This is actually the "cleanest" way to manage a server with lots of users. Instead of hacking away at the main sudoers file, you create a new file:

🔗 Read more: The takeuforward lld course free download: Why Searching for Pirated Tech Courses Usually Backfires

sudo visudo -f /etc/sudoers.d/work-user

Inside, you just put the same configuration line we discussed earlier. This makes it incredibly easy to delete the user’s privileges later—you just delete the file. No need to mess with group memberships or the master config. It’s modular. It’s elegant. It’s what the pros do.

Testing your changes

Don't just assume it worked. Test it. But don't test it by trying to delete your boot partition. Run something harmless like:sudo whoami

If the terminal spits back "root," you’ve successfully managed to add linux user to sudo. If it asks for a password and then tells you you're not in the sudoers file, you probably forgot to log out or you had a typo in the username.

Real-world scenario: The remote server lock-out

Imagine you're SSH'd into a VPS. You add a new user, add them to the sudo group, and then disable root login for security. You hang up the connection, try to log in as the new user, and find out sudo isn't working.

You're locked out.

Always keep your current root session open in one terminal while you test the new user's sudo access in another. It's a simple rule that has saved countless hours of "rescue mode" rebooting and mounting filesystems via a web console.

Step-by-Step Summary for Quick Implementation

- Identify the group: Use

sudofor Ubuntu/Debian andwheelfor Fedora/CentOS. - Execute the command: Run

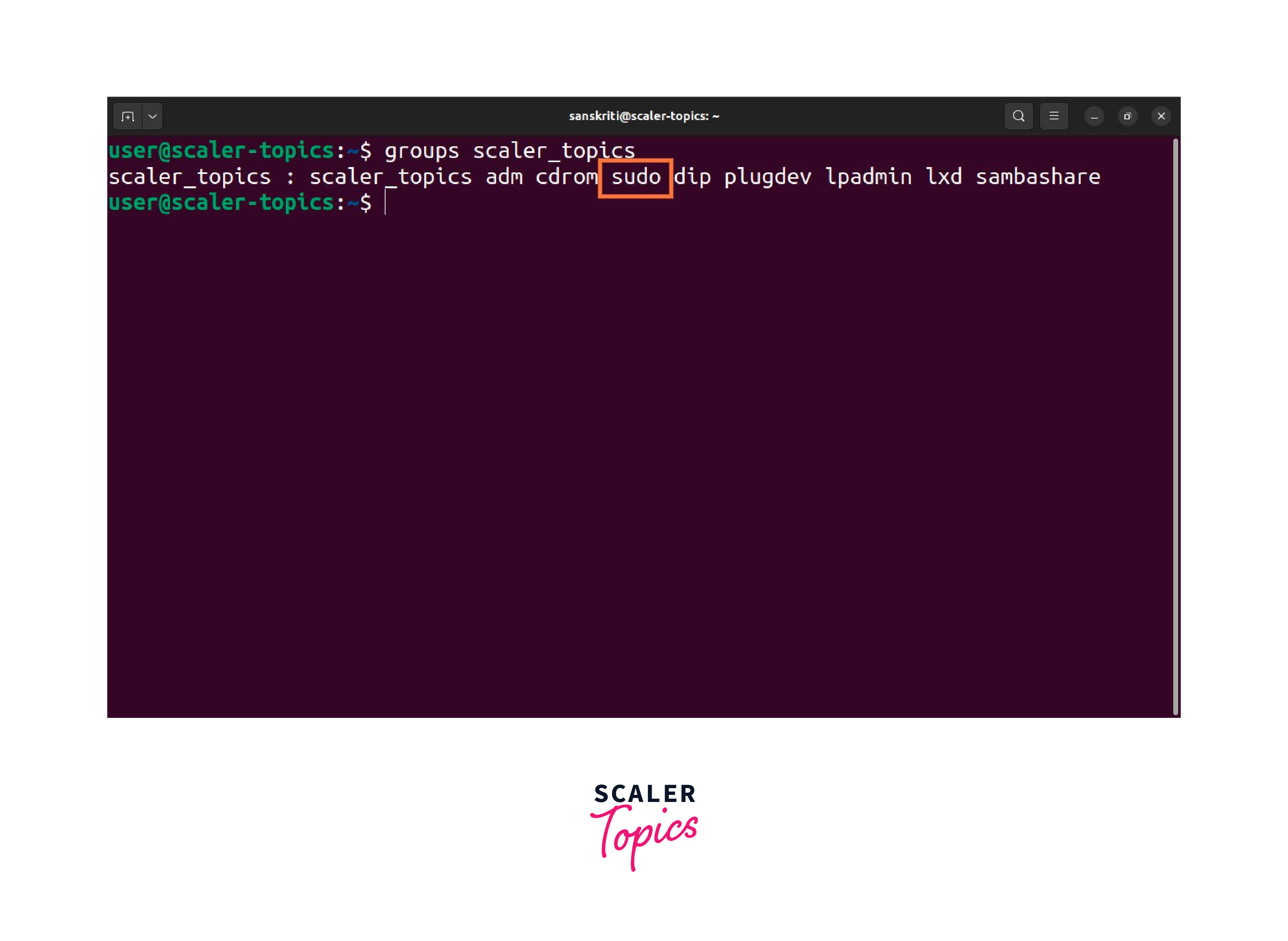

usermod -aG [group] [username]to grant permissions. - Verify the change: Log out completely, log back in, and run

groupsto ensure the group is listed. - The visudo alternative: Use

sudo visudoif you need to grant specific command permissions without group membership. - Use the .d directory: For better organization, place individual user rules in

/etc/sudoers.d/. - Double-check syntax: Always use

visudo -cto check for syntax errors if you manually edited anything.

The next thing you should probably look into is setting up SSH keys for that user. Sudo is great for local security, but if you're still using passwords over SSH, you're only half-protected. Configure your /etc/ssh/sshd_config to disallow password authentication once your sudo user is confirmed and working.