You probably don't think about the wheel and axle simple machine when you're turning a doorknob to get into your bathroom or steering your car onto the highway. It’s just... there. It’s one of those fundamental mechanical advantages humans figured out thousands of years ago, yet most people can’t quite explain how it actually works without getting tripped up on the physics. Honestly, it's basically just a circular lever. If you can understand how a crowbar works, you’re already halfway to understanding why your screwdriver is such a powerhouse.

Mechanical advantage is the name of the game.

📖 Related: Night Lamp With Sensor: Why Most People Are Buying the Wrong One

Think about a screwdriver. You’ve got the handle (the wheel) and the shaft (the axle). When you twist that thick handle, you’re applying force over a larger distance. That translates into a massive amount of torque at the tiny tip of the screwdriver. Without this setup, you’d be trying to turn a screw with your bare fingernails. You’d fail. Your fingers simply can't generate the necessary rotational force because they lack the "leverage" provided by the radius of the handle.

Why the Wheel and Axle Isn't Just for Wagons

Most textbooks start with a picture of a Chariot. That’s fine, but it’s kinda limiting. In reality, the wheel and axle simple machine exists in two distinct "modes" that do opposite things.

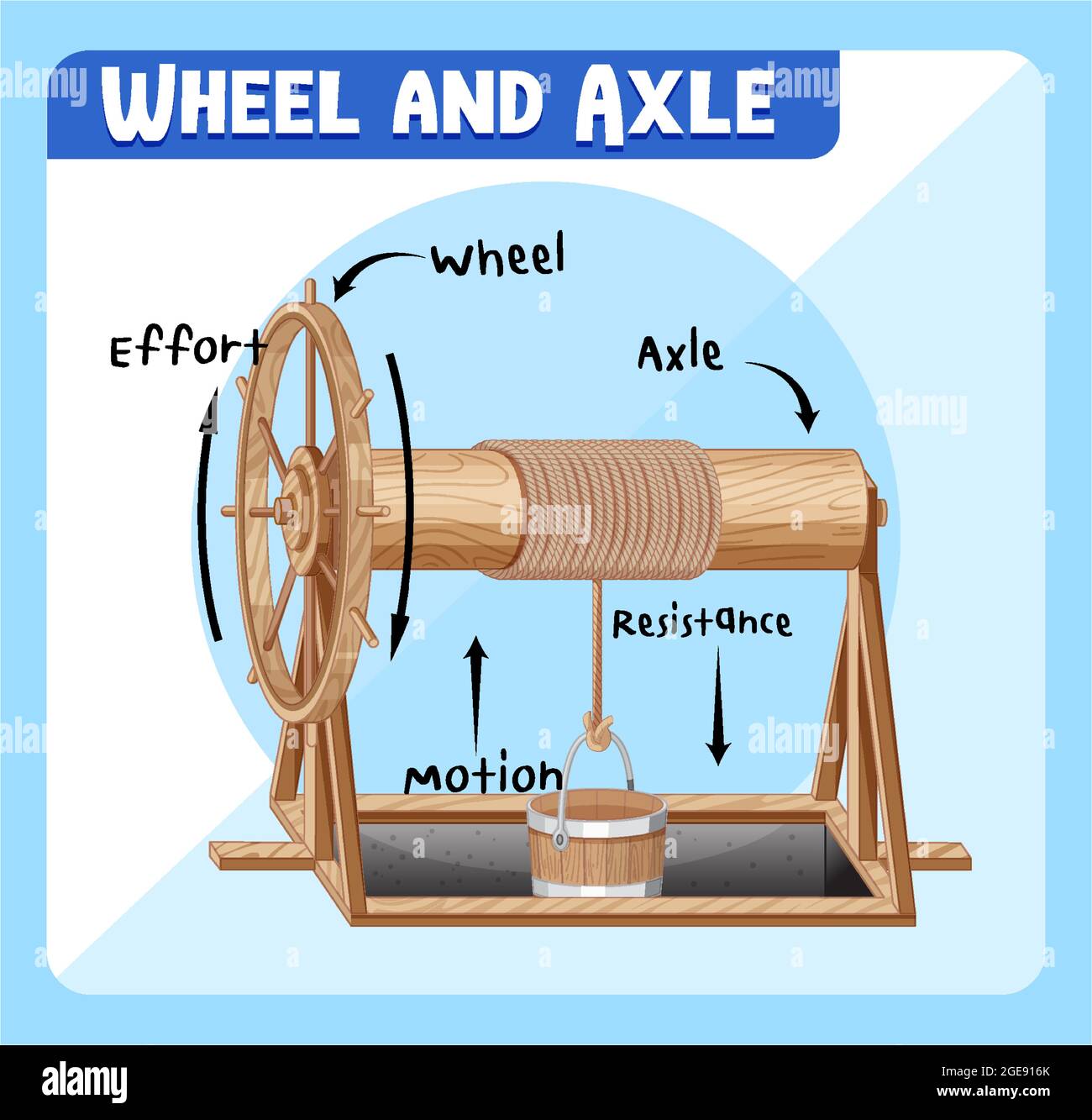

First, there’s the force multiplier. This is the screwdriver example. You apply a little force to a big wheel to move a heavy load on a small axle. Think of a winch on a boat or a classic well where you crank a handle to lift a bucket of water. Because the handle (the wheel) travels a much longer path than the rope being wound around the axle, the work feels "lighter." It’s a trade-off. You move your hand further, but you don't have to pull as hard.

Then there’s the distance multiplier. This is where things get interesting and where most people get confused.

Look at a bicycle. Your legs push the pedals, which are attached to a large sprocket (the wheel). This turns a smaller gear or the wheel itself. In this case, you’re actually applying more force to the axle to make the outer edge of the wheel travel a much greater distance very quickly. If wheels only worked the first way, your car would have a top speed of about four miles per hour, but it could pull a mountain. Since we want speed, we use the axle to drive the wheel.

The Physics of Torque and Radii

To get technical for a second, the relationship is defined by the ratio of the radii. If your wheel has a radius of 10 centimeters and your axle has a radius of 2 centimeters, you have a mechanical advantage of 5.

$$MA = \frac{R_{wheel}}{r_{axle}}$$

This means for every pound of force you put on the wheel, you get five pounds of force at the axle. It's a literal force multiplier. But remember, the universe doesn't give you something for nothing. You have to turn that wheel five times as far as the axle turns. It’s the law of conservation of energy. You aren't "creating" energy; you're just rearranging how it’s applied so your puny human muscles can actually do the job.

Archimedes is usually the guy we credit with formalizing these ideas, but Mesopotamians were using potter's wheels around 3500 BCE. They weren't sitting there calculating Newton-meters. They just knew that spinning a heavy clay disc made it easier to shape a jar.

Real-World Examples You See Every Day

It's everywhere.

- The Doorknob: Try opening a door by grabbing the thin metal spindle behind the knob. It’s nearly impossible. The knob gives you the radius needed to click the latch.

- Steering Wheels: Older cars without power steering had massive steering wheels. Why? Because the driver needed a huge "wheel" to get enough mechanical advantage to turn the heavy "axle" (the steering column) that moved the wheels.

- Electric Fans: The motor turns the axle, which spins the blades. This is a speed-increasing application.

- Pencil Sharpeners: The old-school crank ones. The handle is the wheel, the blades are the axle.

Actually, a common misconception is that a wheel and axle must be able to spin 360 degrees. Not true. A wrench is technically a wheel and axle during the portion of the arc where it’s turning a bolt. The "wheel" is the path your hand takes, and the "axle" is the bolt itself.

The Friction Problem

If the wheel and axle is so great, why did it take so long to invent? Friction.

Early humans could drag things on sleds. To make a wheel and axle work, you need a way to keep the axle attached to the vehicle while letting it spin freely. If the axle rubs too hard against the frame, the friction eats up all your mechanical advantage. This is why the invention of the wheel isn't just about the circle; it's about the "bearing" or the interface where the axle meets the body.

In modern engineering, we use ball bearings to make this movement almost effortless. Without those tiny steel balls, the wheel and axle simple machine in your car's drivetrain would melt from heat within minutes.

Practical Insights for Using This Knowledge

If you’re ever stuck trying to loosen a stuck bolt or move something heavy, remember the radius ratio.

- Increase the lever arm. If a screwdriver isn't working, find one with a fatter handle. The increased radius of the "wheel" gives you more torque on the "axle."

- Check for friction. If a cart is hard to push, the problem usually isn't the weight; it's the resistance at the axle. A drop of oil can do more work than a boost of muscle.

- Understand the trade-off. If you want more speed, you have to apply force to the axle. If you want more power, you have to apply force to the wheel.

The wheel and axle isn't just a museum piece or a grade-school science project. It is the mechanical backbone of the modern world. From the turbines in a hydroelectric dam to the tiny gears in a mechanical watch, we are constantly trading distance for force.

When you look at a Ferris wheel, you're looking at a giant axle (the motor) driving a massive wheel. When you look at a bicycle, you're seeing your own energy being converted from the slow, heavy pressure of your legs into the fast, light rotation of the tires. It’s elegant. It’s simple. And it’s the only reason we aren't still dragging our groceries home on a piece of dried animal hide.

📖 Related: Is CYBELLA Just Another Tech Buzzword or Actually Useful?

Next Steps for Exploration

To really get a feel for this, take a look at the tools in your garage. Measure the diameter of a faucet handle and compare it to the diameter of the valve stem it turns. Calculating that ratio will show you exactly how much your strength is being multiplied. If you're designing a DIY project, like a garden cart or a custom pulley system, always prioritize the axle-to-wheel ratio to ensure you aren't fighting against physics. Look into "rolling resistance" if you want to understand why wheel size matters on different types of terrain—it’s the logical next step in mastering mobility.