You’ve probably seen the clip. It’s a grainy behind-the-scenes video from about a decade ago. Bill Hader is in a recording booth with Matt Stone and Trey Parker, and they are trying to record the voices for a scene involving a fish and a Kanye West parody. They are literally doubled over, unable to breathe because they’re laughing so hard. That’s the reality of the voices of South Park. It isn’t a massive corporate operation with a cast of fifty union actors. It’s basically two guys and a handful of long-time friends making themselves laugh in a small room until their throats hurt.

Most people assume a show that has run for nearly thirty years would have expanded its roster. It hasn't. Not really.

The DNA of the show remains incredibly DIY. While most animated series like The Simpsons or Family Guy rely on a stable of professional chameleons who can do a thousand distinct impressions, South Park is built on the specific, often strained vocal chords of Trey Parker. He does about 70% of the male voices. If you hear a character yelling, crying, or singing a high-pitched ballad about feelings, it’s almost certainly Trey. Matt Stone handles the rest, providing the more grounded, gravelly, or nasal tones. It’s a dynamic that shouldn't work for a multi-billion dollar franchise, yet here we are.

The Pitch Shift Secret Behind Cartman and Kyle

When you hear Eric Cartman scream, you aren't hearing a raw recording. If Trey Parker actually did that voice at that pitch for eight hours a day, he’d be coughing up blood by noon.

The "South Park sound" is a technical trick.

Back in the pilot episode, "Cartman Gets an Anal Probe," the voices were recorded onto analog tape and sped up. Today, they use Pro Tools. They record the lines at a normal pitch—Trey just adds a specific "squeak" and attitude to the delivery—and then the audio engineers pitch it up by about three or four semitones. This preserves the performance's timing but gives it that youthful, bratty timbre. It also hides the fact that the same man is talking to himself. If you pitch Cartman back down, he just sounds like a very angry Trey Parker.

Kyle Broflovski is Matt Stone’s primary vehicle. It’s closer to his natural speaking voice than Stan is to Trey’s, but with a sharper, more frustrated edge. Because Matt and Trey record their lines together, they can riff. They can interrupt each other. That’s why the dialogue in South Park feels faster and more "real" than the stilted, over-rehearsed lines in other sitcoms. They aren't just reading scripts; they’re playing.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

The Women and the Tragedy of Mary Kay Bergman

We have to talk about the women of the show, because that’s where the history gets a bit heavier. In the early years, nearly every female character—Wendy Testaburger, Sharon Marsh, Sheila Broflovski, Mrs. Cartman—was voiced by the immensely talented Mary Kay Bergman.

She was a legend in the voice acting world.

Bergman wasn't just "doing voices"; she gave those characters a soul. When she passed away in 1999, it left a massive hole in the production. The show struggled for a bit to find a permanent replacement, eventually landing on Eliza Schneider and then Mona Marshall and April Stewart. Marshall and Stewart have been the backbone of the female voices of South Park for decades now.

Mona Marshall typically handles the more "vulnerable" or high-pitched roles like Sheila Broflovski (with that iconic New Jersey screech) and Linda Stotch. April Stewart takes on the more grounded roles like Sharon Marsh and Wendy. It’s a divide-and-conquer strategy that has kept the show's female cast feeling consistent, even as the world around them goes insane.

What about Butters?

Butters Stotch is arguably the most beloved character in the modern era of the show. His voice is a masterpiece of sound design.

He’s voiced by Matt Stone, but it’s a very specific performance. The "loo-loo-loo" and the stuttering innocence are based on an actual former producer of the show, Eric Stough. The crew used to tease Stough for being the "nice guy" who didn't swear, and that personality eventually morphed into the child-policeman-supervillain-pimp we know as Butters. It's a "soft" voice. It requires Matt to pull back on his natural aggression, creating a contrast that makes it hilarious when Butters finally snaps.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

The Celebrity Cameo "F-You"

South Park has a weird relationship with celebrities. Most shows beg stars to come on and play themselves. South Park does the opposite.

They usually have Trey Parker do a terrible, intentionally inaccurate impression of a celebrity. Think of the "Lord" version of Steamy Nicks or the various iterations of Kanye West. The inaccuracy is the point. It’s a middle finger to the idea of celebrity worship.

However, they have had real stars. But here's the kicker: they usually give them the most demeaning roles possible.

- George Clooney: He played Sparky, Stan’s gay dog. He just barked.

- Jay Leno: He played Mr. Kitty in an early episode.

- Jerry Seinfeld: He reportedly wanted to be on the show, but when they offered him the role of "Turkey #2" in the Thanksgiving special, his agents declined.

They don't care about your resume. If you’re a star and you want to be among the voices of South Park, you better be prepared to make a fool of yourself or play a non-verbal animal. The only real exception in the early days was Isaac Hayes as Chef. His voice was the "cool" center of the show until his highly publicized departure following the Scientology episode. Since then, the show has largely moved away from having a "moral center" voice, preferring to let the chaos speak for itself.

How the Six-Day Turnaround Affects the Acting

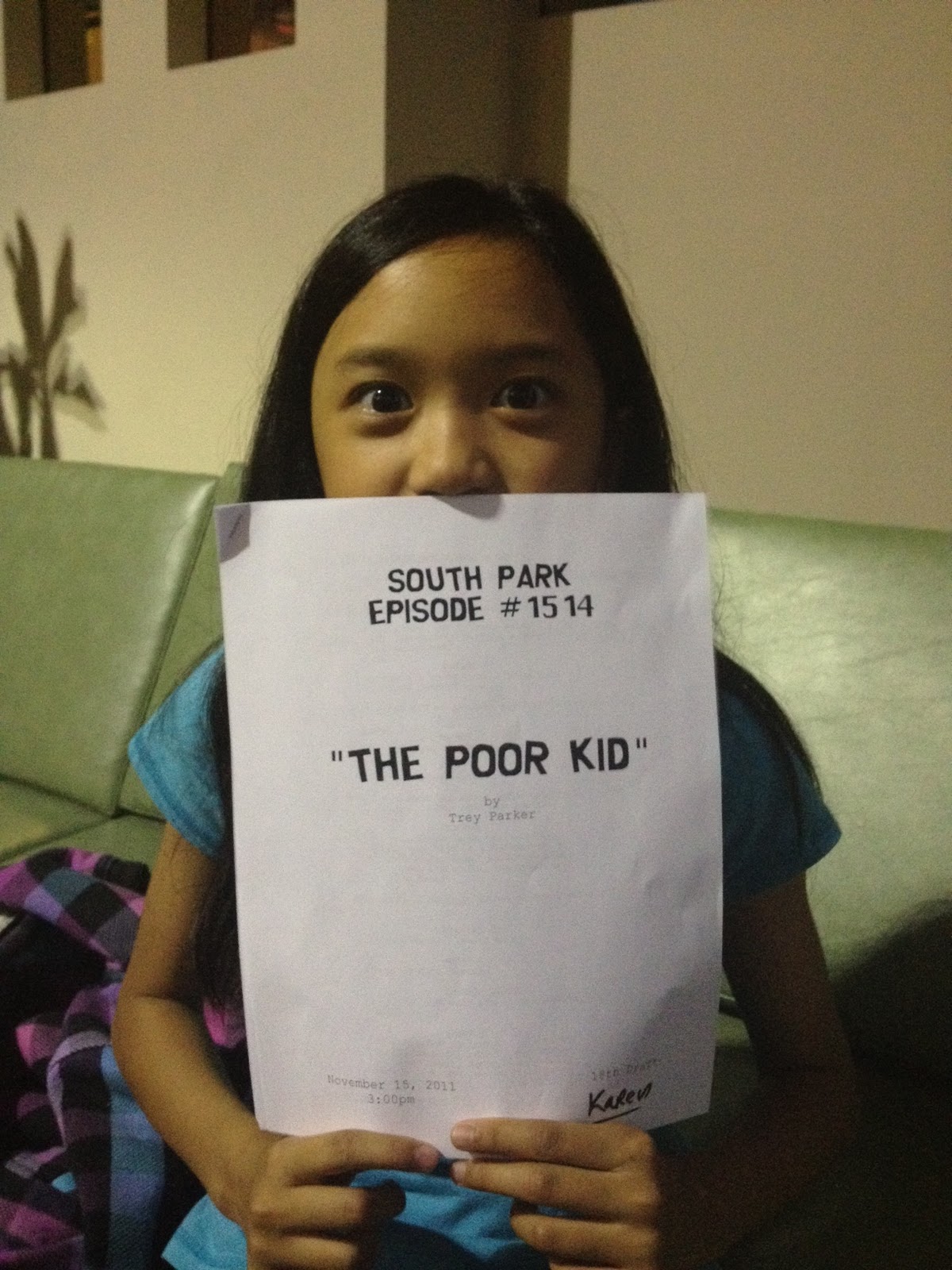

You’ve probably heard about the "6 Days to Air" schedule. It’s legendary. They start an episode on Thursday and it airs the following Wednesday. This creates a frantic, high-energy environment for the voice acting.

There is no time for second-guessing.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

In a typical animated production, voices are recorded months in advance. In South Park, Trey might write a line at 3:00 AM on a Tuesday, record it at 10:00 AM, and it’s on TV thirty-six hours later. This gives the voices of South Park a topicality and a raw energy that you just can't manufacture in a traditional studio system. If a politician says something stupid on Monday, Matt and Trey are in the booth mocking that specific tone by Tuesday afternoon.

Bill Hader, who served as a producer and writer on the show, often remarked on how impressive it is to watch Trey switch between characters. He’ll do a line as Stan, then immediately jump into Randy Marsh (Stan's dad), then flip over to Mr. Garrison. It’s a masterclass in vocal flexibility. Randy Marsh, by the way, has slowly become the "unofficial" lead of the show, mostly because Trey finds it more fun to voice an unhinged, middle-aged man than a cynical fourth-grader.

The Evolution of the Accents

The voices haven't stayed the same. If you go back to Season 1, the characters sound different. They’re flatter.

Cartman was originally much deeper. Over time, his voice became more melodic and manipulative. He started "sing-songing" his threats. This evolution wasn't planned in a boardroom. It happened because the writers realized that the funnier Cartman sounds, the more horrible the things he says can be.

Then there’s Kenny. For years, Matt Stone recorded Kenny’s lines by literally muffling his mouth with his sleeve or his hand. It wasn't just gibberish; Matt was actually saying real lines, just obscured. When Kenny finally spoke clearly in the Bigger, Longer & Uncut movie, it was actually Mike Judge (creator of Beavis and Butt-Head) providing the voice. That's the kind of deep-cut trivia that defines this show’s production history.

Actionable Takeaways for Superfans

If you’re interested in the mechanics of vocal performance or just want to appreciate the show on a deeper level, pay attention to these nuances the next time you watch:

- Listen for the Breath: Unlike "clean" Disney-style voice acting, you can often hear the "mouth sounds" and breaths in South Park. It’s intentional. It makes the characters feel like they are actually in the room.

- The "Randy" Shift: Watch an episode from Season 3 and then one from Season 26. Notice how Randy Marsh’s voice has moved from a generic background dad to a high-energy, theatrical lead. It’s the clearest example of a voice actor (Trey) finding a new "gear" for a character.

- Spot the Guest: Most "additional voices" are provided by staff members. If you hear a random scientist or a background citizen, it's likely a producer or an animator. This gives the town of South Park a consistent, "family" feel.

- The Pitch Check: If you have audio software, try pitching a Cartman clip down by 15-20%. It’s a jarring way to see the "human" behind the monster.

The voices of South Park are a testament to the power of creative control. By keeping the cast small and the production "in-house," Matt and Trey have ensured that the show never lost its specific, weird, and often offensive soul. It’s not about professional polish. It’s about two guys in a room trying to make each other laugh until they can’t speak. That’s why it still works after all these years.

To truly understand the show's impact, your next step should be watching the 6 Days to Air documentary. It’s the most honest look at the creative process ever filmed. You’ll see the bags under their eyes and hear the hoarseness in their throats. It changes the way you hear every "Respect my authorit-ah!" for the rest of your life.