The year was 1991, and Nintendo was basically the only game in town. Then a blue blur showed up. If you look closely at the original Sonic 1 Sonic sprite, you aren't just looking at some old-school pixel art; you’re looking at the moment SEGA decided to wage war. It’s weird to think about now, but that single character model had to carry the weight of an entire corporation on its spiked shoulders.

It worked.

Naoto Ohshima’s design for Sonic didn't just happen. They went through a bunch of iterations—including an armadillo (which became Mighty) and a rounded guy in pajamas (who eventually became Dr. Eggman). But the hedgehog won. When you load up Sonic the Hedgehog on the Genesis, that first frame of Sonic standing there, tapping his foot, changed the industry’s expectations for "character." It wasn't just a hitbox. It was an attitude.

Why the Sonic 1 Sonic Sprite Still Looks Good

Most 16-bit characters from that era feel stiff. Mario, bless his heart, was basically a collection of blocks moving in a somewhat rhythmic fashion. But the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite used a specific trick: "squash and stretch." This is a classic animation principle that SEGA’s team, led by programmer Yuji Naka and designer Hirokazu Yasuhara, baked directly into the game's code.

🔗 Read more: Why the Pokemon Emerald Version Pokedex is Still a Completionist’s Nightmare

When Sonic hits a spring, he doesn't just move upward. He elongates. When he lands, he compresses. This makes the pixels feel like they have weight. Honestly, it’s a bit of a technical miracle considering the Genesis's hardware limitations. The system could only display a limited number of colors on screen at once—usually around 61—and yet the blue mascot looks incredibly vibrant. This is because the palette for the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite uses different shades of cobalt and navy to create a sense of curvature. It’s not just a flat blue shape; it’s a sphere with depth.

The Foot Tap Heard Round the World

The idle animation is probably the most famous part of the original sprite. If you leave the controller alone for a few seconds, Sonic turns toward the screen, looks at you, and starts tapping his foot. He’s annoyed. He has places to be. This was a direct jab at the player. Before this, most video game characters were just puppets for the person holding the controller. Sonic was his own person. He had an ego.

Technical Breakdown: Pixels and Palettes

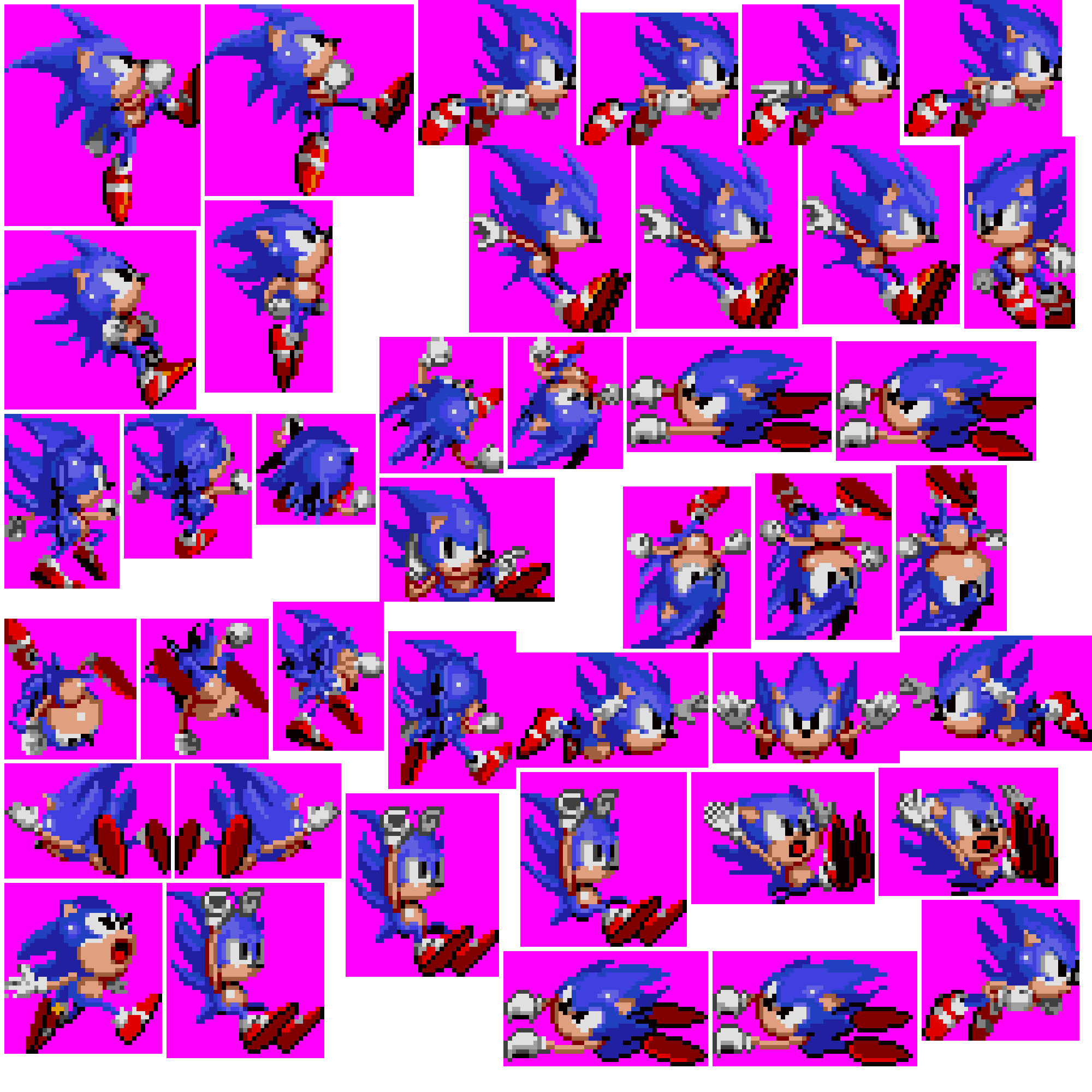

If you’re a modder or a pixel artist, you’ve probably spent time digging through the VRAM to see how this thing is actually built. The Sonic 1 Sonic sprite isn't one single image. It's a collection of 8x8 pixel tiles that the hardware stitches together on the fly. This allowed the developers to swap out pieces of the sprite—like the legs or the head—to create more complex movements without eating up all the cartridge space.

The "running" animation is where the genius really shows. In Sonic 1, when he hits top speed, his legs turn into a "figure-eight" blur. This is a classic cartoon trope translated into code. It creates the illusion of speed that a standard "walking" cycle just couldn't achieve. You can actually see the evolution of this if you compare the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite to the ones in Sonic 2 or Sonic CD. In the later games, the colors get slightly brighter, and the "Super Peel Out" animation adds even more frames, but the foundation—that specific shade of blue and that specific smirk—stayed the same.

The "Illegal" Colors of Sonic

There’s a common misconception that Sonic is just one shade of blue. He isn't. The Sonic 1 Sonic sprite uses a 16-color palette (technically 15 plus transparency).

- Four shades of blue for the body.

- Two shades of peach for the skin/belly.

- White and black for the eyes and shoes.

- Two shades of red for the sneakers.

- A few greys/yellows for the shoe buckles.

Because the Genesis used a 9-bit color palette (512 possible colors), the developers had to be extremely careful with contrast. If the blue was too dark, he’d disappear into the background of levels like Labyrinth Zone. If it was too light, he’d look washed out in Green Hill Zone. They found a "Goldilocks" zone that worked across every environment.

The Cultural Impact of 80 Pixels

It’s hard to overstate how much this specific sprite influenced character design. Before the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite, mascots were usually "cute" or "heroic" in a very bland way. Sonic brought "edge." That smirk in the title screen? That was a calculated move by SEGA of America’s marketing team to appeal to teenagers who thought Nintendo was for little kids.

Interestingly, the Japanese version of the sprite was slightly different in the concept phase. Some early sketches had Sonic with a human girlfriend named Madonna and a rock band. Thankfully, those were scrapped, leaving us with the clean, iconic look we know today. The simplicity is what makes it work. You can draw Sonic from memory because his silhouette is so distinct. Even if you turn him into a solid black shadow, you still know it’s him because of those quills.

Common Misconceptions About the Original Sprite

People often think the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite is the same one used in Sonic 2. It’s not.

While they look similar at a glance, the Sonic 2 sprite is actually a bit more "polished." The shading on the quills is different, and his "waiting" animation is slightly faster. Also, the Sonic 1 sprite has a very specific "victory" pose after beating a boss—the finger wag—that feels a bit more aggressive than the later versions.

Another weird detail: Sonic’s arms. In the original Sonic 1 Sonic sprite, his arms are peach-colored. In some later iterations and cartoons, people get confused and think they should be blue. But no, the OG pixels clearly show peach arms. It’s a point of contention among fans to this day, but the 1991 sprite is the source of truth here.

How to Study the Sprite for Modern Dev

If you're making your own game, there's a lot to learn from how SEGA handled the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite.

First, look at the "anticipation" frames. Before Sonic jumps, there is a tiny, almost imperceptible frame where he crouches. This gives the jump "pop." Without that one frame, the movement would feel floaty and cheap.

Second, notice the "running" lean. The faster Sonic goes, the more his body tilts forward. This communicates physics to the player without needing a speedometer on the screen. You feel the velocity because the sprite tells you it's happening.

Actionable Insights for Pixel Artists

If you want to recreate or iterate on the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite style, keep these rules in mind:

- Restrict your palette. Don't use 200 colors. Use 15. It forces you to make better choices about where light hits the character.

- Focus on the silhouette. If the character doesn't look cool as a solid black shape, the design is too busy.

- Animate for personality. Don't just make a "walk cycle." Make a "character-specific walk." How would this person walk if they were late for a bus? How would they walk if they just won the lottery?

- Use the "Line of Action." Even in 16-bit, Sonic's body usually follows a curved line that directs the player's eye toward the direction of movement.

The Sonic 1 Sonic sprite isn't just a relic of the past; it’s a masterclass in visual communication. It told a generation of kids that games could be fast, cool, and a little bit rebellious. Every time you see a modern indie game with "fluid" pixel art, you're seeing the DNA of that 1991 masterpiece.

To really understand the impact, go back and play the original on a CRT monitor if you can. The way the colors bleed slightly on an old tube TV actually makes the Sonic 1 Sonic sprite look smoother than it does on a crisp modern 4K screen. The developers knew exactly how those pixels would look on a 1990s television, and they designed every single dot to take advantage of it. That’s not just art—that’s engineering.

If you're looking to dive deeper into this world, your next move should be looking at the original design documents by Naoto Ohshima. They show the "geometry" of Sonic—how he's built out of circles and triangles. Understanding that underlying structure is the key to why that sprite has stayed relevant for over thirty years while so many other mascots have been forgotten. Check out the "Sonic Jam" art gallery if you can find a copy or a scan online; it's a goldmine for this stuff.

Next Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Download a sprite sheet of the original Sonic 1 animations to study the frame-by-frame breakdown of the "rolling" jump.

- Research "Sonic 1 SMS" to see how the sprite was downgraded for the 8-bit Master System—it’s a fascinating look at how to maintain character identity with even fewer pixels.

- Experiment with "palette swapping" the blue tones to see how much the lighting changes the feel of the character's "speed."