People love a good mystery. Honestly, the idea that aliens or some "lost high-tech civilization" built the Giza plateau is a fun story for a late-night documentary, but it’s kinda insulting to the actual Egyptians who lived and breathed in the dust. When you look at the evidence, the truth about how the pyramids were made is actually way more impressive than science fiction. It wasn't magic. It was a massive, country-wide logistical operation that combined simple physics with an almost terrifying amount of human willpower.

Think about the scale. We’re talking about 2.3 million stone blocks for the Great Pyramid alone. Most of those weigh around 2.5 tons. Some, like the granite slabs above the King’s Chamber, weigh upwards of 80 tons. If you tried to do that today, you’d need a fleet of specialized cranes and a budget that would make a tech billionaire sweat. But the Egyptians had copper chisels, wooden sleds, and the Nile.

It started with the rock

Before a single stone was laid, they had to find the material. Most of the Great Pyramid is made of "common" yellowish limestone. Luckily for Khufu, the pharaoh who commissioned it, that limestone was available right there on the Giza plateau. They basically built the pyramid next to its own grocery store. Workers used copper tools to pick at the soft stone, creating channels, and then used wooden wedges soaked in water to crack the blocks free. Water makes wood expand. Physics does the heavy lifting.

But the "casing stones"—the shiny, white limestone that used to make the pyramids glow like salt in the sun—came from Tura. That's across the river. And the red granite? That came from Aswan. Aswan is 500 miles south.

Moving mountains on water

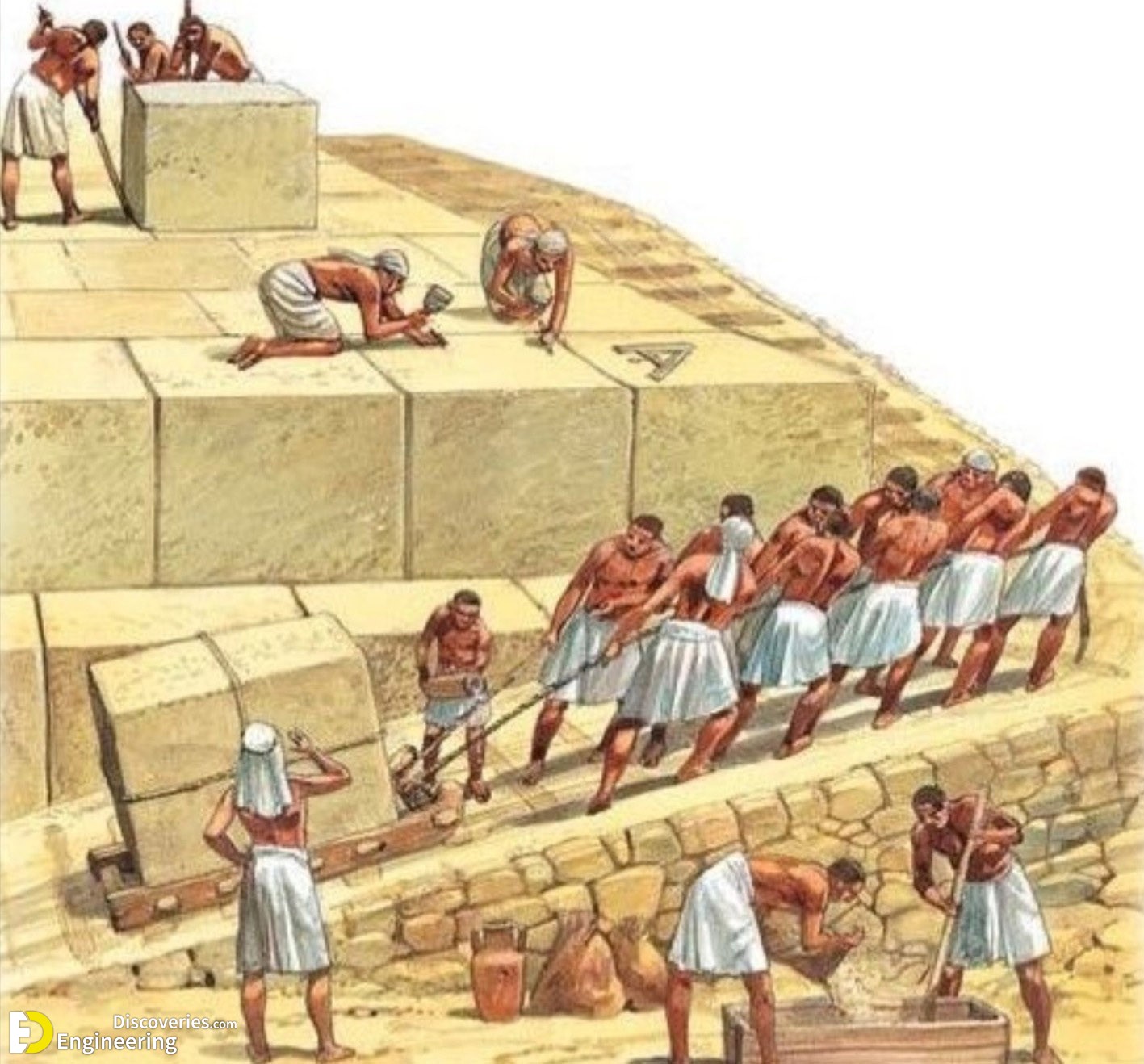

How do you move an 80-ton block 500 miles without a combustion engine? You wait for the rain. Or rather, the flood. The Nile’s annual inundation was the secret weapon of Egyptian engineering. Mark Lehner, a leading archaeologist who has spent decades excavating the "Lost City" of the pyramid builders, discovered evidence of massive harbor works near the Sphinx.

Basically, the Egyptians dug canals that brought the river right to the foot of the plateau. They built huge wooden barges, loaded the granite during the high-water season, and floated those monsters downstream. It was a masterpiece of seasonal timing. If they missed the flood window, they were stuck for a year.

The big ramp debate

This is where things get heated in the world of Egyptology. We know how the pyramids were made in terms of materials, but the "up" part is still debated. You’ve probably seen the classic "straight ramp" in movies. One long hill leading to the top.

Mathematically? That’s a nightmare.

🔗 Read more: Woman on a Plane: What the Viral Trends and Real Travel Stats Actually Tell Us

To keep the slope manageable for men pulling sleds, a straight ramp reaching the top of the 481-foot Great Pyramid would have to be over a mile long. It would contain as much volume as the pyramid itself. It’s just not efficient.

Jean-Pierre Houdin, a French architect, proposed a wild but compelling theory: an internal ramp. He suggests they used an external ramp for the bottom third, then built a corkscrew tunnel inside the structure to haul the rest of the stones. It sounds crazy until you see the scans. Recent thermal imaging and muon radiography (which uses cosmic rays to see through stone) have revealed "voids" and "anomalies" that match exactly where a ramp might be.

Wet sand and friction

But even with a ramp, how do you pull a 2.5-ton block? You don't just "heave-ho" on dry sand. If you try to pull a heavy sled on dry sand, the sand bunches up in front of the runners. It’s like trying to push a shopping cart through deep mud.

Physicists from the University of Amsterdam figured this one out in 2014 by looking at Egyptian wall paintings. They saw a guy standing on the front of a sled pouring water onto the sand. For years, people thought it was a ritual or just "cleaning." Nope. It was lubrication. The right amount of water creates "capillary bridges" between sand grains, making the ground stiff and cutting the friction in half. This little trick reduced the number of workers needed by 50%.

Who were these people?

Let's clear one thing up: they weren't slaves. The "Jewish slaves built the pyramids" thing is a total myth popularized by Hollywood and some misunderstandings of the Book of Exodus. We have the receipts. Literally.

Archaeologists found the "Workmen’s Village" at Giza. It wasn't a prison camp. It was a bustling town with bakeries, breweries, and medical facilities. We’ve found skeletons of workers who underwent successful brain surgery and had broken bones that healed perfectly. That kind of medical care was expensive. You don't give "brain surgery" to a slave you consider expendable.

The tax of labor

Most of the labor came from farmers. In Egypt, when the Nile flooded, you couldn't farm. Your fields were underwater for months. Instead of sitting around, the pharaoh called in his "corvée" labor tax. You’d go to Giza, get fed high-protein meals (we found tons of cattle and goat bones), drink decent beer, and work for the "living god." It was a source of national pride. Groups even had names like "The Friends of Khufu" or "The Drunkards of Menkaure." They left graffiti inside the pyramid's stress-relieving chambers bragging about their teams.

💡 You might also like: Where to Actually See a Space Shuttle: Your Air and Space Museum Reality Check

Precision that defies logic

Even if you accept the ramps and the labor, the precision of how the pyramids were made is still spooky. The Great Pyramid is aligned to true north within three-sixtieths of a degree. It’s more accurate than the Meridian Building at the Greenwich Observatory in London.

How? No compasses back then.

They likely used the stars. One theory involves "circumpolar stars." You take two stars that rotate around the pole, hold a plumb line, and mark where they are when they're perfectly vertical. Bisect that angle, and you have true north. It’s simple, elegant, and incredibly tedious.

The base is also level within three-quarters of an inch. Over thirteen acres. To achieve that, they might have cut narrow channels in the rock, filled them with water, and used the water level as a giant, natural "spirit level."

The "Iron" problem

People often ask how they cut the stone so perfectly without steel. Iron wasn't a thing yet. They used copper, which is soft.

But they didn't just use copper. They used copper plus grit.

By using a copper saw or drill and feeding it abrasive sand (like crushed quartz), they created a "liquid sandpaper" effect. The copper was just the carrier; the sand did the cutting. We’ve found drill cores that show the Egyptians were cutting into hard granite at a rate of several millimeters per revolution. It’s slow, agonizing work, but when you have 20 years and 20,000 people, you get it done.

📖 Related: Hotel Gigi San Diego: Why This New Gaslamp Spot Is Actually Different

The internal structure: A stress test

If you pile up six million tons of rock, the bottom stones are going to crush under the weight. Or, if you leave a hollow room inside (like the King’s Chamber), the ceiling will collapse.

To prevent this, the Egyptians built "relieving chambers." Above the King’s Chamber are five small compartments capped with massive granite beams. Above those, they built a gabled roof made of giant limestone blocks angled against each other. This diverts the weight of the pyramid around the room and into the core of the structure. It’s a primitive but brilliant version of a modern skyscraper’s load-bearing frame.

Lessons from the "failures"

We know how the pyramids were made because the Egyptians practiced. They didn't just wake up and build the Great Pyramid. They messed up first.

At Meidum, the pyramid literally fell apart because they built it on sand and the outer casing slipped. At Dashur, the "Bent Pyramid" changes angle halfway up. Why? Because the builders realized the 54-degree slope was too steep and the structure was becoming unstable. You can actually see the "Oh crap" moment in the masonry where they shifted to a safer 43-degree angle.

These "failures" are the best evidence we have. They show a learning curve. They show humans figuring it out through trial and error, not aliens handing down blueprints.

Actionable insights for history buffs

If you're planning to visit or just want to understand this better, keep these points in mind to cut through the "woo-woo" noise you find online:

- Look at the tool marks: When you're at Giza, look for the "saw marks" on the black basalt pavement near the Great Pyramid. You can see the circular paths of the abrasive drills.

- Check the village: Don't just look at the pyramids. Look at the ruins of the Workers' Village. It's the most human part of the site.

- Follow the water: Notice the topography. The Giza plateau was chose because it was a massive limestone quarry, not just because it looked cool.

- Respect the math: Understand that "primitive" does not mean "stupid." The Egyptians used the Golden Ratio and Pi not necessarily because they had the formulas written down, but because they used physical tools like ropes and circles that naturally produce those proportions.

The pyramids weren't built by a mystery civilization that disappeared. They were built by a civilization that was obsessed with bureaucracy, logistics, and the Nile. It was the world's first massive public works project. It wasn't about the stone; it was about the organization of an entire nation toward a single, impossible goal. That is much more interesting than a UFO.