You probably remember a poster in your middle school science classroom. It was likely bright purple or green, featuring a clip-art magnifying glass and a neat, vertical list. It told you that science is a straight line. First, you ask a question. Then you do some research, make a guess, run a test, and boom—you've discovered a universal truth.

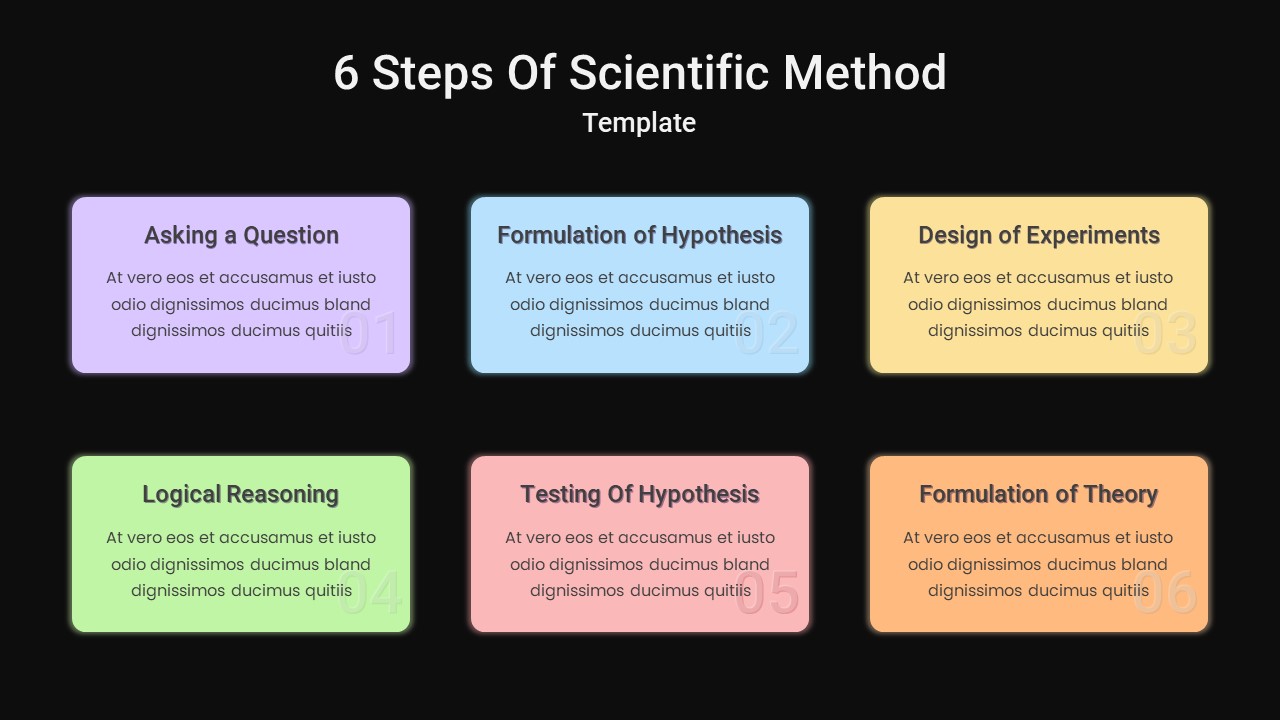

Honestly? That’s not how it happens. Real science is messy. It’s a lot of "wait, why did that happen?" and "well, that’s definitely not right." The five steps to the scientific method are less of a ladder and more of a loop. A messy, frustrating, beautiful loop. If you look at how NASA engineers troubleshoot a thruster or how biologists at the Salk Institute hunt for cancer markers, they aren't just checking boxes. They are using a framework to keep their own biases from lying to them.

Because that's the thing: your brain is a liar. It wants to see patterns where there aren't any. It wants to be right. The scientific method exists solely to prove yourself wrong before someone else does.

The Observation Phase: Where Curiosity Hits the Wall

Everything starts with looking. But not just glancing. It's about noticing a gap.

Sir Alexander Fleming didn't set out to change the world in 1928. He was actually kind of a messy guy. He came back from vacation and noticed that some of his Petri dishes containing Staphylococcus were contaminated with mold. Boring, right? Most people would have just washed the dish. But he noticed that the bacteria weren't growing near the mold.

That "huh, that's weird" moment is the first of the five steps to the scientific method. In a formal sense, we call it Observation. In reality, it's just paying attention when things don't go as planned.

If you're a developer today, this is your "bug." You expected the code to execute in 20ms, but it took 200ms. You don't know why yet. You just know the reality doesn't match the expectation. To do this right, you have to be specific. "The sky is blue" is an observation, but "the sky is a deeper blue at the zenith than at the horizon" is a useful observation. It gives you a lever to pull.

Formulating a Hypothesis (The Educated Guess Everyone Gets Wrong)

Here is where the textbooks fail us. They tell you a hypothesis is an "if-then" statement. While that's a decent way to teach kids, real scientists think in terms of falsifiability.

Karl Popper, a heavy hitter in the philosophy of science, argued that if a claim can't be proven false, it isn't scientific. If I say, "invisible, undetectable dragons live in my garage," you can't prove me wrong. That's not a hypothesis. It's a story.

💡 You might also like: Apple Watch 42mm Band: Why the Sizing Still Confuses Everyone

A real hypothesis for the five steps to the scientific method needs to be a target. You are putting a bullseye on your chest. You might hypothesize that Staphylococcus growth is inhibited by a secretion from Penicillium notatum mold.

This step is basically you making a bet. You've seen something weird (Step 1), and now you're saying, "I bet it’s because of X." But you have to be okay with losing that bet. In fact, most researchers spend their lives losing these bets. It’s part of the gig.

The Experiment: Rigging the Game Against Yourself

Now we get to the fun part. The experiment.

This is where you try to break your hypothesis. If you're testing a new battery chemistry, you don't just charge it once and call it a day. You bake it. You freeze it. You discharge it until it screams.

An experiment needs variables.

- The Independent Variable: The thing you change (like the amount of mold extract).

- The Dependent Variable: The thing you measure (how much bacteria died).

- The Control: The group you leave alone so you have something to compare against.

Without a control group, you're just messing around. Imagine testing a new "smart water" that claims to improve focus. If you give it to ten people and they all feel focused, does that mean the water worked? No. Maybe they were just excited to be in a study. You need ten other people drinking regular tap water while believing it’s the smart water. That’s the placebo effect, and it’s the gold standard for a reason.

💡 You might also like: What Does Alts Mean? Why Everyone is Talking About Alternate Accounts and Assets

Data Analysis: Turning Noise into Signal

Data is loud. It’s messy. It rarely looks like a clean curve.

When scientists talk about the five steps to the scientific method, this fourth step is where the math happens. You’re looking for "statistical significance." This basically means: "Is this result real, or did I just get lucky?"

In 2012, when physicists at CERN were looking for the Higgs Boson, they weren't looking for a single "aha!" moment. They were looking at trillions of particle collisions. They needed a "5-sigma" level of certainty. That is a 1 in 3.5 million chance that the result was a fluke.

You probably don't need 5-sigma to figure out why your sourdough bread didn't rise, but you do need to look at the numbers objectively. Did the bread rise higher at 80 degrees than at 70? Or was it just a slightly different brand of flour? You have to account for the "noise."

Drawing Conclusions (And Admitting You Might Be Wrong)

The final step isn't about being right. It’s about what happens next.

If your data supports your hypothesis, awesome. You haven't "proven" it—science doesn't really do "proof" like math does—but you've failed to disprove it. If the data says you're wrong? That’s actually more interesting.

The five steps to the scientific method usually end with more questions. Fleming didn't just stop at "mold kills bacteria." He had to figure out how to mass-produce it. He had to see if it killed humans too (spoiler: it doesn't, usually).

This is why we have peer review. You show your work to a bunch of other grumpy experts and say, "Try to find the hole in my logic." If they can't find one, you might be onto something.

Why This Matters Beyond the Lab

You use this every day without realizing it.

Your car won't start (Observation). You think maybe the battery is dead (Hypothesis). You turn on the headlights to see if they're dim (Experiment). They're bright as day (Data). So, it's not the battery; it’s probably the starter (New Hypothesis/Conclusion).

That’s the scientific method in a nutshell. It’s a tool for sanity in a world full of misinformation. It’s a way to navigate the unknown by being systematically skeptical of your own first impressions.

💡 You might also like: How to Remove Write Protection on USB Pen Drive When Nothing Else Works

Actionable Ways to Apply the Scientific Method Today

- Audit Your Biases: Next time you're sure about something, try to think of one piece of evidence that would prove you wrong. If you can't think of any, you're not being scientific; you're being dogmatic.

- Change One Variable at a Time: If you're trying to fix a bad sleep schedule, don't change your pillow, your room temp, and your caffeine intake all at once. You won't know what worked. Change one thing. Wait three days. Record the result.

- Keep a Log: Human memory is incredibly fallible. We remember our "wins" and forget our "losses." If you’re testing a new marketing strategy or a new diet, write down the raw data. The numbers don't have egos.

- Seek Out Disproof: Don't look for people who agree with you. Look for the smartest person who disagrees with you and try to understand their data.

Science isn't a collection of facts in a textbook. It’s a verb. It’s something you do. By following the five steps to the scientific method, you aren't just learning about the world—you're learning how to see it clearly.