You’ve probably seen the posters. That iconic white orbiter strapped to a giant orange tank, flanked by two skinny white boosters, screaming toward the heavens in a cloud of fire. It looks simple enough on a T-shirt. But if you actually sit down and look at the original blueprint of space shuttle systems, you realize it wasn't just a rocket. It was a mechanical nightmare held together by genius and grit.

The Space Transportation System (STS) was basically a flying brick with wings that had to act like a glider, a laboratory, and a heavy-lift truck all at once. NASA engineers didn't just wake up and build this. They had to reconcile the fact that the Air Force wanted a huge payload bay for satellites while scientists wanted a stable platform for microgravity experiments. The result? A vehicle so complex that even today, decades after its first flight, we still haven't built anything quite like it.

The Orbiter: A Glider with an Attitude

The "shuttle" part—the orbiter—is what everyone remembers. But calling it a plane is a bit of a stretch. When it was coming back from orbit, it had the aerodynamic properties of a falling safe. Honestly, it only "flew" because the computers were fast enough to keep it from tumbling.

Looking at the blueprint of space shuttle airframes, you see the airframe was primarily 2024-T3 aluminum. If you've ever worked on a Cessna, you know the stuff. But a Cessna doesn't hit the atmosphere at Mach 25. To keep the aluminum from melting into a puddle, NASA had to glue on over 24,000 individual ceramic tiles. No two tiles were exactly the same shape. Think about that for a second. Every single tile had a specific home on the belly of the ship, hand-fitted like the world’s most expensive jigsaw puzzle.

The thermal protection system (TPS) was the heartbeat of the design. Without it, the "blueprint" was just a very fast coffin. Engineers like Maxime Faget, who was a titan at NASA during the Mercury and Apollo days, fought hard over the shape of those wings. The "delta wing" design was a compromise. The military needed "cross-range capability," which basically meant the shuttle could land at a different spot than where it started its descent if it had to dodge a geopolitical mess. That requirement dictated the entire silhouette of the vehicle.

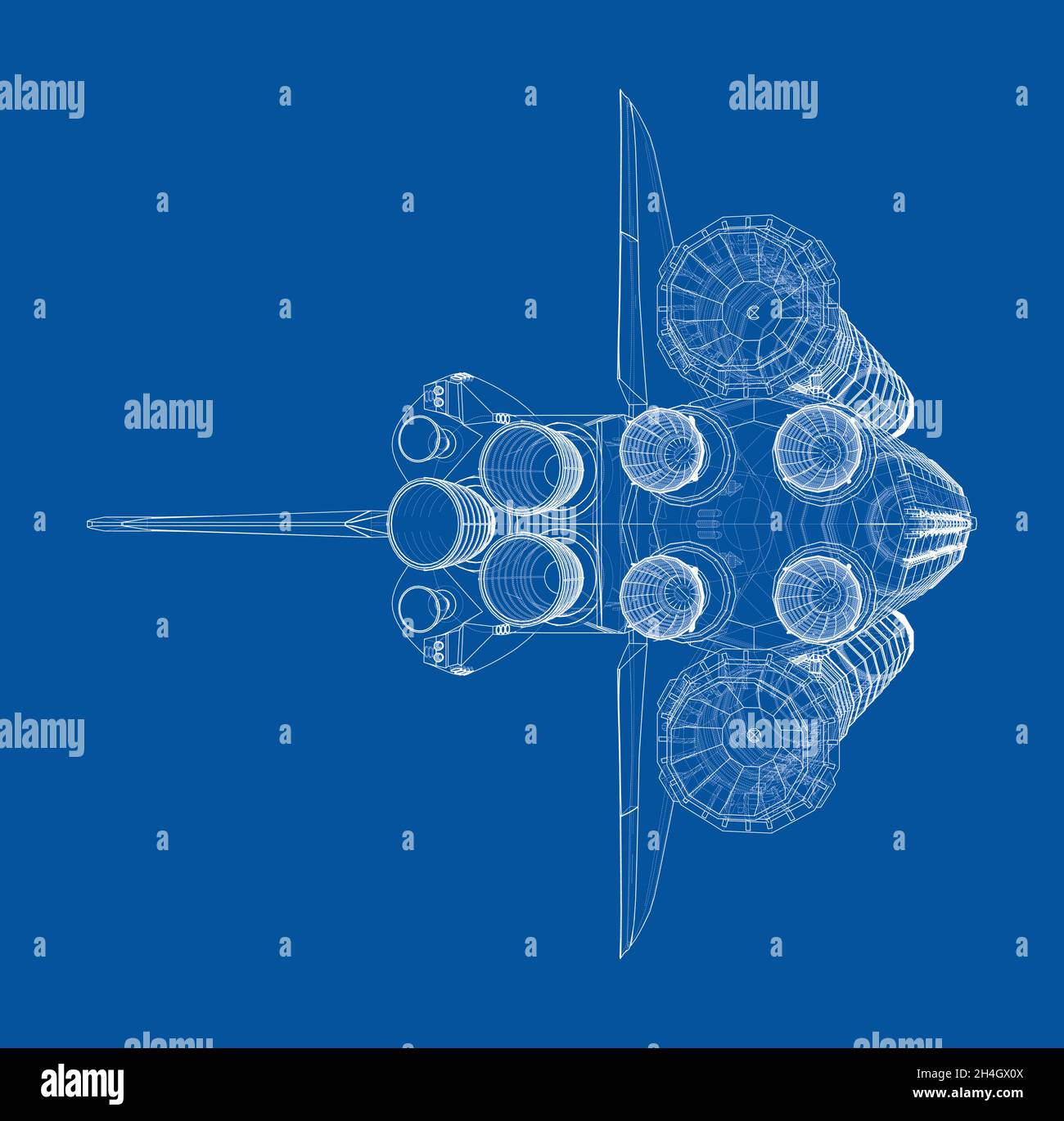

Those Massive Engines and the Plumbing From Hell

If you look at the back of the orbiter, you see the three Space Shuttle Main Engines (SSME), also known as the RS-25. These are arguably the most complicated pieces of machinery ever built by humans. Period.

Most rockets are "disposable." You use them once, they fall in the ocean, and you build a new one. The SSME was designed to be reused. That sounds great on paper, but in reality, it meant the plumbing was insane. These engines used liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen. Hydrogen is a nightmare to work with. It's the smallest molecule in the universe; it leaks through microscopic cracks that other gases wouldn't even notice.

- The high-pressure fuel turbopump was the size of a V8 engine but produced as much horsepower as 28 Union Pacific locomotives.

- The temperature inside the combustion chamber was 6,000 degrees Fahrenheit—higher than the boiling point of iron.

- At the same time, the liquid hydrogen flowing through the cooling jackets was at -423 degrees.

The blueprint of space shuttle propulsion systems shows a "staged combustion cycle." Most rockets just dump some exhaust overboard to power their pumps. Not the shuttle. It fed the exhaust back into the main chamber to squeeze every last ounce of efficiency out. It was efficient, sure, but it was also temperamental. A single tiny piece of debris could cause a "contained shutdown," or worse, an uncontained one.

The External Tank and the Solid Rockets

You can't talk about the blueprint without the "stack." The External Tank (ET) was the only part of the whole rig that wasn't reused. It was basically a giant thermos for the fuel. That orange color? That’s just the spray-on foam insulation. Originally, they painted the tanks white (look at STS-1 and STS-2 photos), but they realized the paint weighed about 600 pounds. They figured, why waste 600 pounds on aesthetics? So they left it orange.

Then you have the Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs). These things provided 80% of the lift at liftoff. Once you light a solid rocket, you can’t turn it off. It’s like a giant firework. You’re going until the fuel is gone. This created a massive safety debate during the design phase. If something went wrong in the first two minutes, you couldn't just "shut down" the SRBs. You were along for the ride.

The Cockpit: Where 1970s Tech Met the Stars

If you stepped into a shuttle cockpit in the 1980s, you’d see hundreds of "toggle switches." It looked like a high-tech version of a 747. It wasn't until the "Glass Cockpit" upgrades in the late 90s and early 2000s that they got those fancy multi-function displays we see in modern jets.

✨ Don't miss: IonQ Stock Price Chart: What Most People Get Wrong About the Quantum Leap

The computers were the real shocker. The original blueprint of space shuttle avionics relied on IBM AP-101 computers. They had less memory than a modern digital watch. We're talking about roughly 400 kilobytes of memory. To make it work, the crew had to "load" different software packages for different phases of flight. There was a program for "ascent" and a different one for "orbit." If you didn't swap the tapes correctly, you were in trouble.

NASA mitigated the risk of a computer crash by using five of them. Four ran the same software and voted on every decision. If one disagreed, the other three would "vote it out" and ignore it. The fifth computer ran entirely different software written by a different team of programmers just in case there was a bug in the primary code. Redundancy was the only way they could sleep at night.

Why the Design Failed (And Why It Succeeded)

People love to criticize the shuttle now. They say it was too expensive, too dangerous, and didn't fly often enough. And yeah, they're sorta right. The original goal was 50 flights a year. We never got close. The maintenance between flights was a nightmare. Every tile had to be inspected. Every engine had to be practically rebuilt.

But look at what it did. It built the International Space Station (ISS). It fixed the Hubble Space Telescope. It brought back satellites from orbit and repaired them. No other spacecraft has ever had that kind of "hands-on" capability. The blueprint of space shuttle operations was about flexibility. It was a tool for a time when we didn't know exactly what we'd need to do in space, so we built something that could do everything.

How to Explore the Blueprints Yourself

If you’re a real nerd for this stuff, you don't have to take my word for it. The technical documentation is actually out there if you know where to look.

💡 You might also like: Why the Cord Cut by a Cord Cutter Isn’t Just About a Cable Bill

- NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS): This is the holy grail. Search for "STS Press Manuals" or "Orbiter Systems Data." You’ll find thousands of pages of schematics that show everything from the toilet plumbing to the Ku-band antenna deployment mechanisms.

- The Haynes Owners' Workshop Manual: Believe it or not, there is a "Haynes Manual" for the Space Shuttle. It's written by experts like Dr. David Baker, who actually worked on the program. It breaks down the blueprints into something a normal human can understand.

- Visit a Museum: Seeing Discovery at the Udvar-Hazy Center or Atlantis at Kennedy Space Center is the only way to appreciate the scale. When you stand under the engines, you realize the blueprints don't do the size justice.

The legacy of the shuttle isn't just the missions it flew. It’s the engineering culture it created. We learned how to manage massive, complex systems. We learned about the fragility of heat shields. We learned that sometimes, the most "advanced" solution (like a reusable space plane) is actually much harder than the "simple" solution (like a capsule on a stick).

Every time you see a SpaceX Falcon 9 land or a Dragon capsule splash down, you’re seeing lessons learned from the shuttle's blueprints. We moved back to capsules for safety, but we kept the dream of reusability. The shuttle was a magnificent, flawed, beautiful bridge to the future. It’s worth remembering not just for the fire and smoke, but for the millions of lines of code and the hand-glued tiles that made it possible.

Your Next Steps for Deep Learning

If you want to truly master the technical side of this, start by downloading the 1982 STS-1 Press Kit. It is the most "human-readable" version of the technical blueprint ever released. From there, look into the Challenger and Columbia accident reports. These documents are grim, but they provide the most honest assessment of the shuttle's design flaws ever written. Understanding why a machine fails is often more instructive than understanding why it works. Look for the "Rogers Commission Report" specifically; it’s a masterclass in engineering ethics and system design.