You’re scrolling. It happens every night. You’re on Netflix, or maybe TikTok, and suddenly a video pops up that feels like it was plucked directly from the inside of your brain. It’s weird. It’s almost invasive. But it’s just math. Specifically, it’s recommendation engine machine learning doing exactly what it was hired to do.

Most people think these systems are just "tracking" them. That's a bit of a simplification. Honestly, these algorithms don't care about you as a person; they care about the mathematical shadow you leave behind. They are trying to solve a massive discovery problem. Imagine walking into a library with ten million books and no signs. You’d leave. Companies like Amazon or Spotify can't afford for you to leave, so they build these digital librarians that predict your cravings before you even feel them.

The Cold Start and the Matrix

Every recommendation system starts with a massive headache called the "Cold Start" problem. If you’re a new user, the machine knows zero about you. It’s guessing. It might show you the most popular items—the "trending" stuff—just to see how you react. This is basic. It’s the digital equivalent of a waiter asking if you want the house special because they don't know your palate yet.

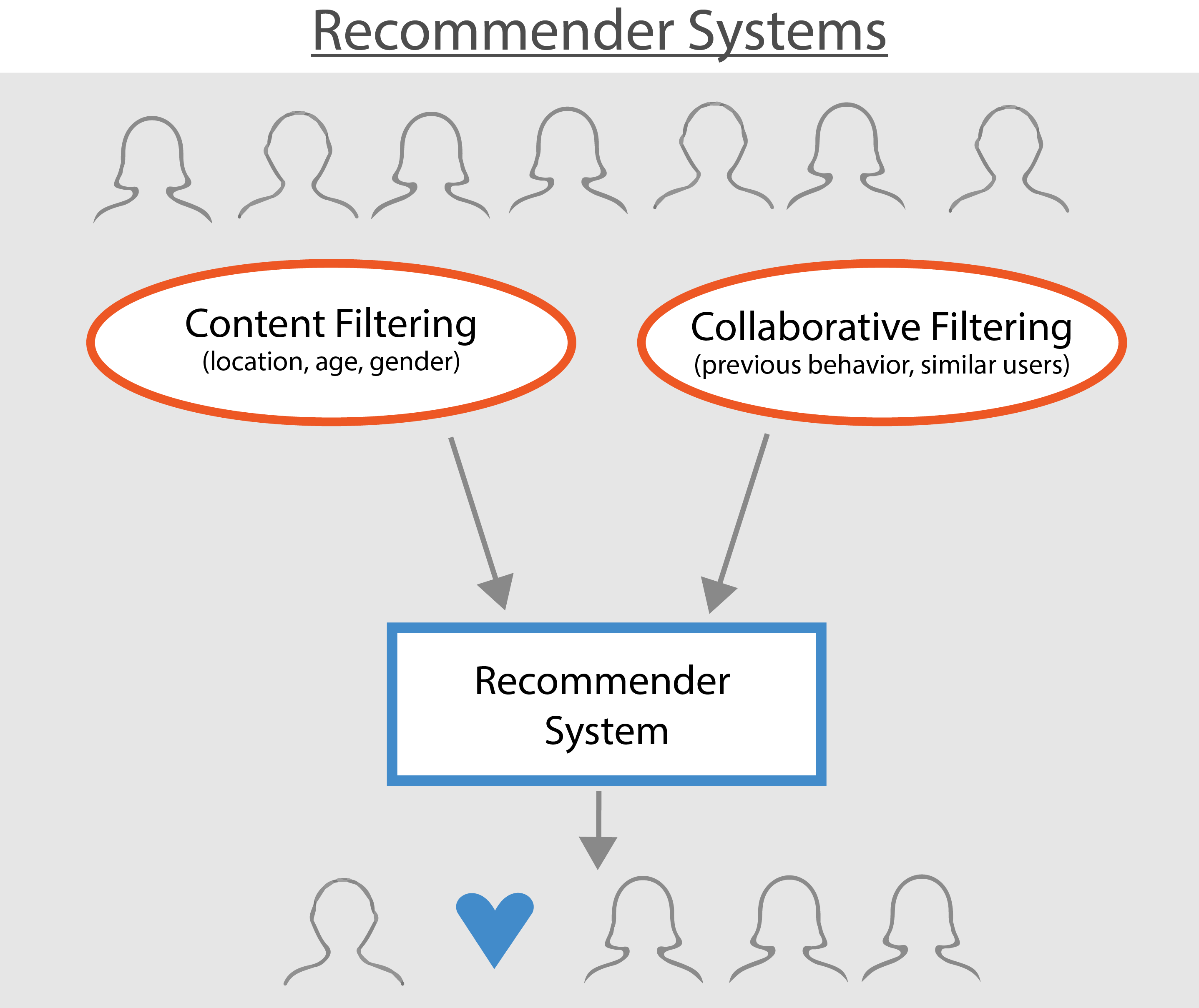

Once you start clicking, the recommendation engine machine learning kicks into high gear using something called Collaborative Filtering. This is the heavy lifter. You’ve probably seen the "Customers who bought this also bought..." line. That is the classic implementation. It doesn't actually look at the product features; it looks at user behavior patterns.

If User A likes items 1, 2, and 3, and User B likes items 1 and 2, the math suggests User B will probably like item 3. It’s a game of pattern matching. Scientists like Travis Ebesu have written extensively on how neural collaborative filtering has moved past simple matrix factorization into deep learning territory. We aren't just comparing two rows in a spreadsheet anymore. We are looking at high-dimensional "embeddings" where your preferences are mapped as coordinates in a space with hundreds of different axes.

Why Content-Based Filtering is the Backup Plan

What if the item is new? If a musician uploads a song to Spotify, no one has listened to it yet. Collaborative filtering fails here. This is where Content-Based Filtering saves the day. The system looks at the "metadata." For a song, that’s the tempo, the genre tags, the key, or even the "acousticness."

Pandora’s Music Genome Project is the gold standard for this. They had actual humans (musicologists) tag songs with hundreds of attributes. Most modern systems use AI to do this tagging now. They "listen" to the audio or "read" the product description to find similarities. It's less about what people do and more about what the thing is.

The Ghost in the Code: Deep Learning and Transformers

Lately, things have changed. We’ve moved away from simple "if this, then that" logic. The big players—YouTube, Pinterest, Alibaba—now use Deep Neural Networks (DNNs).

YouTube’s architecture, famously detailed in a 2016 paper by Paul Covington and his team, uses a two-stage process. First, "candidate generation" narrows down millions of videos to a few hundred. Then, a "ranking" network scores those hundreds to find the top ten you see on your homepage. It considers "freshness." It knows if you just watched a tutorial on fixing a sink, you probably don't want to see a different sink tutorial immediately after. You want the next step. Or maybe a break.

The Attention Mechanism

Then there’s the Transformer model. Originally built for translating languages (like GPT-4), Transformers are now being used for recommendation engine machine learning. Why? Because they are incredible at understanding sequence.

💡 You might also like: What Was the Silk Road Website and Why Does it Still Scaring the Feds?

Think about your browsing history. The order matters. If you buy a camera, then a lens, then a tripod, the sequence tells a story of a growing hobby. A traditional algorithm might just see "photography gear." A Transformer-based recommender sees a progression. It understands that your intent on Tuesday might be completely different from your intent on Monday, even if you’re looking at the same category of items.

When the Machines Get It Wrong

We've all been there. You buy one blender for your mom’s birthday and for the next six months, Amazon thinks your entire personality is "Blender Enthusiast." It’s annoying. This is a failure of "diversity" and "serendipity" in the algorithm.

If an engine only gives you what it knows you like, you end up in a filter bubble. You get bored. The "Exploitation vs. Exploration" trade-off is the hardest part of building these things. Exploitation is giving you the 10th Marvel movie because you liked the first nine. Exploration is showing you a weird indie documentary to see if you’ll bite.

Too much exploitation leads to stagnation. Too much exploration makes the user feel like the app doesn't "get" them.

The Feedback Loop Problem

There’s a darker side to this. Bias. If a recommendation engine machine learning system sees that people tend to click on sensationalist news, it will show more sensationalist news. This creates a feedback loop. The algorithm isn't "evil," but it is optimized for engagement. If engagement correlates with anger or shock, the machine will inadvertently promote those feelings.

Researchers like Ruocheng Guo have highlighted how "causal inference" is the next frontier. Engineers are trying to teach machines not just what happened, but why it happened. Did you click the video because you liked it, or just because it had a bright red thumbnail? Distinguishing between those two is the difference between a good recommendation and a cheap trick.

The Tech Stack Behind the Scenes

If you wanted to build one of these today, you wouldn't start from scratch. You’d likely use tools like:

- TensorFlow Recommenders (TFRS): A library specifically for building complex models.

- Apache Spark: For handling the massive amounts of data (ETL) required to train the models.

- Redis or Pinecone: Vector databases that allow the system to find "similar" items in milliseconds.

- Amazon Personalize: A managed service that lets you throw data at a pre-built model and get recommendations back via API.

It’s expensive. Running these models in real-time takes massive computational power. That’s why your phone sometimes gets hot when you’re scrolling through a media-heavy feed. The app is literally doing math in the background to decide what to show you next.

Real-World Nuance: It's Not All Retail

We talk a lot about shopping, but recommendation engine machine learning is everywhere now.

In healthcare, researchers are using these engines to suggest personalized treatment plans based on a patient’s genetic history and previous reactions to medicine. It’s the same math as Netflix, but the stakes are life and death instead of "what should I watch while I eat pizza."

In the job market, LinkedIn uses these systems to match candidates to recruiters. The nuance here is "two-sided matching." The candidate has to like the job, but the company also has to like the candidate. It’s a much harder mathematical puzzle than suggesting a pair of shoes.

✨ Don't miss: How Does a Compact Disk Work? The Lasers and Logic Behind the Shiny Plastic

How to Actually Improve Your Results

If you're a developer or a business owner looking to leverage this, stop obsessing over the "best" algorithm. There isn't one. The "best" system is the one that understands your specific data's quirks.

1. Clean your data. Garbage in, garbage out. If your product tags are messy, your content-based filtering will be a disaster. Spend the time to standardize your metadata.

2. Focus on "Implicit" signals. People lie. They might "Like" a documentary to look smart, but they’ll spend four hours watching reality TV. Track watch time, hover time, and repeat visits. That’s where the truth is.

3. Implement a "Re-ranking" layer. Don't just trust the raw score from your model. Add a final layer of business logic. Maybe you want to prioritize items that are in stock or have a higher profit margin. Maybe you want to filter out items the user has already seen five times this week.

4. Test for Serendipity. Measure how often users engage with something outside their usual "niche." If that number is zero, your algorithm is too tight. Loosen the constraints.

💡 You might also like: The History of US Fighter Jets and Why We Keep Building Them

Recommendation engines are evolving from simple suggestion tools into "anticipatory interfaces." The goal is a world where you don't search at all because the right information finds you. It sounds like sci-fi, but we’re already halfway there. Just look at your "Recommended for You" tab.

Actionable Next Steps

- Audit your current feedback loops: Look at your click-through rates (CTR) versus long-term retention. High CTR but low retention usually means your engine is "clickbaiting" users rather than providing value.

- Explore Hybrid Models: Combine collaborative and content-based approaches. This mitigates the Cold Start problem while still benefiting from user behavior data.

- Invest in Vector Databases: If you’re scaling, moving to a vector-search approach (using embeddings) will drastically reduce latency and improve the "relevance" of your suggestions compared to old-school keyword matching.

- Monitor for Model Decay: Recommendation patterns change. What people liked in 2024 isn't what they'll like in 2026. Set up a pipeline to retrain your models weekly, if not daily.