You’re sitting in a plastic chair, staring at a bag of juice and a tiny bandage on your arm. Maybe the nurse just told you that you have "the good stuff." Or maybe you’ve just always wondered why your donor card has a little minus sign next to a letter. It feels exclusive. It feels like a secret club. But when we talk about how rare is a negative blood type, we aren't just talking about a cool trivia fact for your dating profile. We are talking about a biological quirk that influences everything from emergency room protocols to prenatal care.

Blood is weird.

Most of the world—roughly 85% of us—walks around with a protein called the Rh factor sitting on the surface of our red blood cells. If you have it, you’re positive. If you don't? You’re negative. It sounds like a missing piece, but for the 15% of the population that lacks this protein, it’s just their normal. However, "rare" is a relative term. In some parts of the world, being Rh-negative is almost unheard of, while in others, it’s a significant chunk of the neighborhood.

The Numbers Game: How Rare Is a Negative Blood Type Globally?

Let's get into the weeds. If you're in the United States, the chances of you being Rh-negative are about 1 in 7. That's not "winning the lottery" rare, but it’s "hard to find a specific shoe size in a clearance rack" rare.

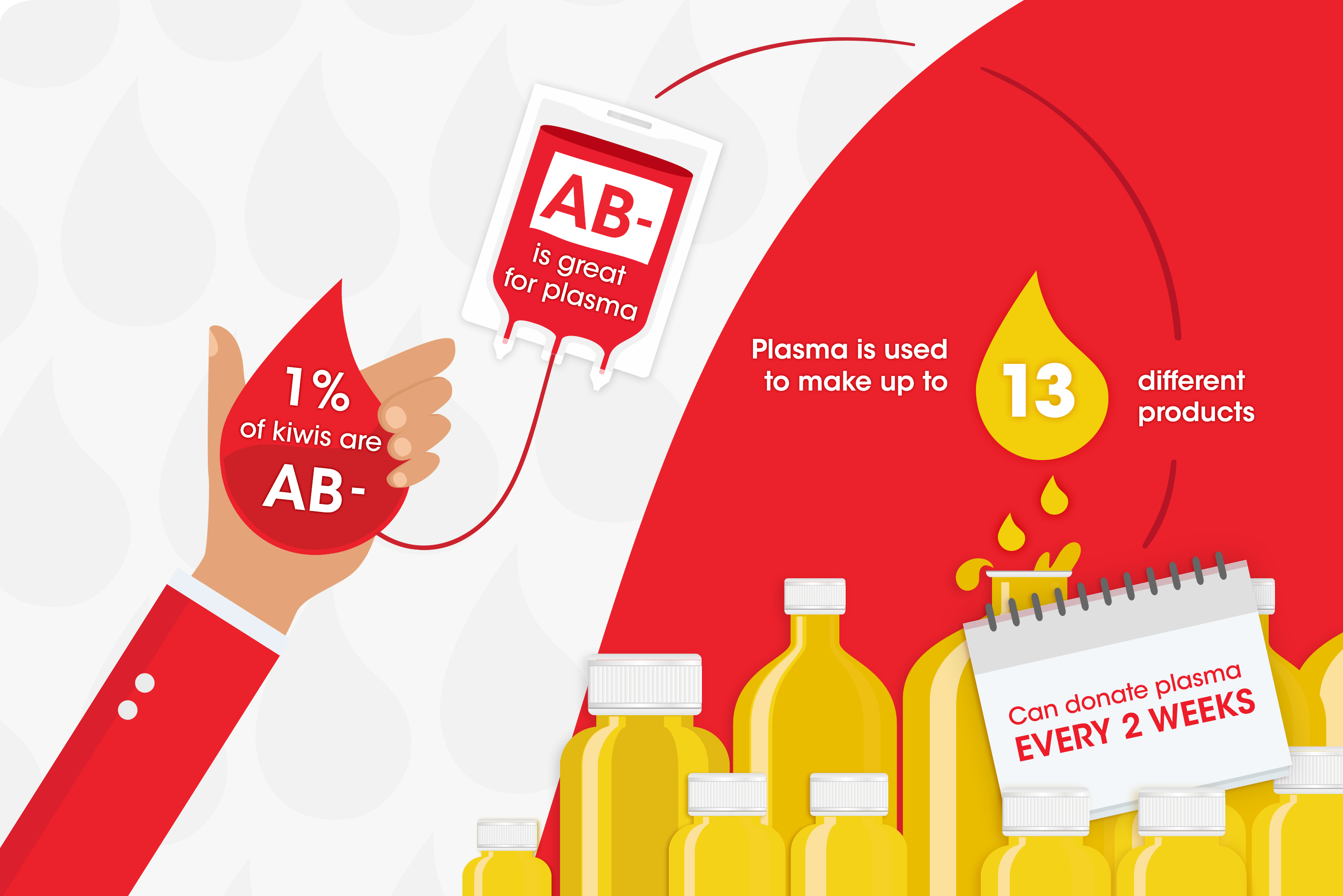

According to the American Red Cross, the breakdown is pretty lopsided. O-negative is often cited as the most "useful" rare type because it's the universal donor. About 7% of the U.S. population has it. Then you have A-negative at 6%, B-negative at 2%, and the undisputed king of rarity: AB-negative. Only 1% of people have AB-negative blood. If that’s you, congratulations, you’re basically a unicorn.

But here is where it gets fascinating. Genetics doesn't care about borders, but it definitely tracks with ancestry.

The Rh-negative trait is most common in people of European descent. If you look at the Basque people living in the borderlands between France and Spain, the frequency of Rh-negative blood skyrockets to nearly 35%. Some researchers have spent decades trying to figure out why this specific group has such a high concentration. On the flip side, if you look at populations in Asia or Africa, the negative trait is incredibly scarce. In many Asian countries, less than 1% of the population is Rh-negative. This creates a massive logistical nightmare for hospitals in those regions when a traveler with O-negative blood needs a transfusion.

It's a strange biological divide.

One day you're just a person with blood, and the next, you're a "rare commodity" depending on which continent you’re standing on. This isn't just about statistics; it's about the literal supply and demand of human life.

💡 You might also like: Children’s Hospital London Ontario: What Every Parent Actually Needs to Know

Why Does the "Negative" Even Exist?

Evolution rarely does things by accident, but the Rh-negative factor is a bit of a head-scratcher.

Biologically, there isn't a massive "advantage" to being Rh-negative. In fact, for a long time in human history, it was a distinct disadvantage, particularly for childbirth. When an Rh-negative mother carries an Rh-positive baby, her body might treat the baby's blood like a foreign invader. This is called Rh incompatibility. Before modern medicine, this led to countless lost pregnancies.

Nowadays, we have RhoGAM. It’s a shot that basically tells the mother’s immune system to "chill out" and ignore the baby's Rh-positive cells. It’s a miracle of science, honestly. Without it, the "negative" trait might have eventually been phased out by natural selection because of the complications it caused in reproduction.

Some people love to get weird with this. You’ll find corners of the internet claiming Rh-negative people are descended from aliens or ancient Nephilim because the trait is "unnatural."

It’s not.

It’s just a mutation. Like blue eyes or lactose tolerance. Mutations happen. Sometimes they stick around because they offer a hidden benefit—like how sickle cell trait offers some protection against malaria—but for Rh-negative blood, we haven't found that "silver lining" yet. It might just be a neutral hitchhiker in our DNA.

The Universal Donor Burden

If you have O-negative blood, your phone probably rings every time the Red Cross has a slow week.

Why? Because O-negative is the "Universal Donor." In a trauma center, when a patient is bleeding out and there’s no time to test their blood type, the doctors reach for the O-negative. It’s the only type that can be given to anyone without causing a fatal immune reaction.

📖 Related: Understanding MoDi Twins: What Happens With Two Sacs and One Placenta

This creates a weird paradox. Even though how rare is a negative blood type suggests O-negative isn't the most rare (remember, AB-negative holds that trophy), it is the most in demand.

- O-negative can go to anyone.

- A-negative can go to A-, A+, AB-, and AB+.

- B-negative can go to B-, B+, AB-, and AB+.

- AB-negative can only go to other AB types (but they can receive all negative types).

If you’re AB-negative, you are a "universal plasma donor." While your red blood cells are picky, your plasma is the liquid gold that anyone can take. It’s like the mirror version of O-negative.

Living with a Negative Type: What You Actually Need to Know

Most people go their whole lives without thinking about their blood type until they're pregnant or in an accident. But if you know you're negative, there are a few real-world implications that go beyond just being a frequent flyer at the blood drive.

First, the emergency scenario. If you have a rare negative type and you're traveling in a region where that type is scarce (like parts of Southeast Asia), it’s not a bad idea to know where the international hospitals are. In some countries, blood banks simply don't stock Rh-negative blood because the local population doesn't have it.

Second, the pregnancy factor. This is the big one. If you are a woman with a negative blood type, you need to be proactive. Modern prenatal care handles Rh incompatibility easily, but it requires that first step: knowing your type. Doctors will typically administer RhoGAM at 28 weeks and again after delivery if the baby is positive.

It’s simple. It’s routine. But it’s non-negotiable.

The Future of "Rare" Blood

We are moving toward a world where "rare" might not mean "unavailable." Researchers are working on "enzyme-converted" blood. Essentially, they are trying to find ways to "strip" the proteins off the surface of red blood cells to turn Type A or Type B into Type O.

Think about that. If we could use a chemical process to turn common blood into the universal O-negative type, the question of how rare is a negative blood type becomes a historical footnote rather than a medical crisis. We aren't there yet—it's still mostly in the lab phase—but the progress is real.

👉 See also: Necrophilia and Porn with the Dead: The Dark Reality of Post-Mortem Taboos

Until then, we rely on the 15% of the population that lacks that Rh protein.

Actionable Steps for the "Negative" Community

If you've discovered you're part of this 15%, or the even smaller 1% of AB-negatives, don't just sit on that info. Here is how to actually manage it:

1. Get a Digital Record: Don't rely on a card in your wallet that might get lost. Ensure your blood type is listed in the Medical ID section of your smartphone. First responders are trained to look there.

2. Don't Wait for the Disaster: Blood banks have a "shelf life." Red blood cells only last about 42 days. If everyone waits for a natural disaster to donate, the blood won't be processed and tested in time to help the initial wave of victims. Routine donations are what actually keep the "rare" shelves stocked.

3. If You're Pregnant, Speak Up: Even though it's standard, verify at your first prenatal appointment that your Rh status is on the front page of your chart. It prevents any delay in getting the necessary antibody screenings.

4. Track Your Iron: People with rare blood types often feel pressured to donate frequently. That’s noble, but it can lead to anemia. If you’re a regular donor, make sure you’re supplementing with iron or eating a diet heavy in heme iron (red meat, spinach, lentils) to keep your own levels healthy.

5. Understand the "Power Red" Option: If you are O-negative or A-negative, ask about "Power Red" donations. This allows you to donate two units of red cells while returning your plasma and platelets to your body. It’s more efficient for the blood bank and often easier on your recovery.

Being a "negative" isn't a medical condition. It's just a variation in the human blueprint. It makes you a vital part of a global safety net that most people don't even realize exists until they need it. Whether you're the 1-in-100 AB-negative or the 1-in-15 O-negative, your biology is essentially a backup generator for the rest of the world.